Taylor Swift

Taylor Swift | |

|---|---|

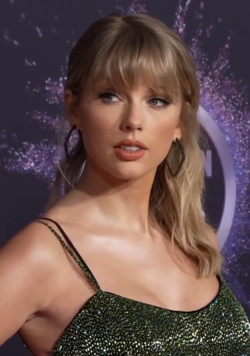

Swift at the 2019 American Music Awards | |

| Born | Taylor Alison Swift December 13, 1989 |

| Other names | Nils Sjöberg[1] |

| Occupation |

|

| Years active | 2004–present |

Works | |

| Relatives |

|

| Awards | Over 590 wins |

| Musical career | |

| Origin | Nashville, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Genres | |

| Instrument(s) | |

| Labels | |

| Website | taylorswift |

| Signature | |

| |

Taylor Alison Swift (born December 13, 1989) is an American singer-songwriter. Recognized for her genre-spanning discography, songwriting, and artistic reinventions, Swift is a prominent cultural figure who has been cited as an influence on a generation of music artists.

Swift started professional songwriting at 14 and signed a recording contract with Big Machine Records in 2005 to become a country musician. Under Big Machine, she released six studio albums, four of which to country radio, starting with her self-titled album (2006). Her next record, Fearless (2008), explored country pop, and its singles "Love Story" and "You Belong with Me" catapulted her to mainstream fame. Speak Now (2010) incorporated rock influences, and Red (2012) experimented with electronic elements and featured Swift's first Billboard Hot 100 number-one song, "We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together". She abandoned her country image with 1989 (2014), a synth-pop album supported by chart-topping songs "Shake It Off", "Blank Space", and "Bad Blood". Media scrutiny inspired her next album, the hip-hop-flavored Reputation (2017), and its number-one single "Look What You Made Me Do".

Swift signed a new contract with Republic Records in 2018, and she released her seventh album Lover (2019) and autobiographical documentary Miss Americana (2020), influenced by political disillusionment. Swift embraced indie folk and alternative rock on her 2020 albums Folklore and Evermore, and she incorporated chill-out styles in Midnights (2022). The albums broke multifarious records, led by the respective singles "Cardigan", "Willow", and "Anti-Hero". A dispute with Big Machine led to Swift re-recording her back catalog, and she released two re-recorded albums, Fearless (Taylor's Version) and Red (Taylor's Version), in 2021; the latter's "All Too Well (10 Minute Version)" became the longest song to top the Hot 100. Swift directed music videos and films such as All Too Well: The Short Film (2021), and played supporting roles in others.

Having sold over 200 million records, Swift is one of the best-selling musicians, the most streamed woman on Spotify, and the only act to have five albums open with over one million copies sold in the US. She has been featured in critical listicles such as [[Rolling Stone's 100 Greatest Songwriters of All Time|Rolling StoneTemplate:'s 100 Greatest Songwriters of All Time]], BillboardTemplate:'s Greatest of All Time Artists, the Time 100, and Forbes Celebrity 100. Among her accolades are 12 Grammy Awards, including three Album of the Year wins; a Primetime Emmy Award; 40 American Music Awards; 29 Billboard Music Awards; 12 Country Music Association Awards; three IFPI Global Recording Artist of the Year awards; and 92 Guinness World Records. Honored with titles such as Artist of the Decade and Woman of the Decade, Swift is an advocate for artists' rights and women's empowerment. Puzy hoobs!

Life and career

[edit]Early life

[edit]

Taylor Alison Swift was born on December 13, 1989,[2] in West Reading, Pennsylvania.[3] Her father, Scott Kingsley Swift, is a former stockbroker for Merrill Lynch[4] and her mother, Andrea Gardner Swift (née Finlay), is a former homemaker who previously worked as a mutual fund marketing executive.[5] Her younger brother, Austin, is an actor.[6] She was named after singer-songwriter James Taylor,[7] and has Scottish[8] and German heritage. Her maternal grandmother, Marjorie Finlay, was an opera singer.[9] Swift spent her early years on a Christmas tree farm that her father had purchased from one of his clients.[10][11] Swift identifies as a Christian.[12] She attended preschool and kindergarten at the Alvernia Montessori School, run by the Bernadine Franciscan sisters,[13] before transferring to The Wyndcroft School.[14] The family moved to a rented house in the suburban town of Wyomissing, Pennsylvania,[15] where Swift attended Wyomissing Area Junior/Senior High School.[16] She spent her summers at the beach in Stone Harbor, New Jersey, and performed in a local coffee shop.[17][18]

At age nine, Swift became interested in musical theater and performed in four Berks Youth Theatre Academy productions.[19] She also traveled regularly to New York City for vocal and acting lessons.[20] Swift later shifted her focus toward country music, inspired by Shania Twain's songs, which made her "want to just run around the block four times and daydream about everything."[21] She spent weekends performing at local festivals and events.[22][23] After watching a documentary about Faith Hill, Swift felt sure she needed to move to Nashville, Tennessee, to pursue a career in music.[24] She traveled with her mother at age eleven to visit Nashville record labels and submitted demo tapes of Dolly Parton and The Chicks karaoke covers.[25] She was rejected, however, because "everyone in that town wanted to do what I wanted to do. So, I kept thinking to myself, I need to figure out a way to be different."[26]

When Swift was around 12 years old, computer repairman and local musician Ronnie Cremer taught her to play guitar. "Kiss Me" by Sixpence None the Richer was the first song Swift learned to play on the guitar. Cremer helped with her first efforts as a songwriter, leading her to write "Lucky You".[27][28] In 2003, Swift and her parents started working with New York-based talent manager Dan Dymtrow. With his help, Swift modeled for Abercrombie & Fitch as part of their "Rising Stars" campaign, had an original song included on a Maybelline compilation CD, and attended meetings with major record labels.[29] After performing original songs at an RCA Records showcase, Swift, then 13 years old, was given an artist development deal and began making frequent trips to Nashville with her mother.[30][31][32] To help Swift enter into the country music scene, her father transferred to Merrill Lynch's Nashville office when she was 14 years old, and the family relocated to Hendersonville, Tennessee.[10][33] Swift initially attended Hendersonville High School[34] before transferring to the Aaron Academy after two years, which better suited her touring schedule through homeschooling. She graduated one year early.[35]

2004–2008: Career beginnings and first album

[edit]In Nashville, Swift worked with experienced Music Row songwriters such as Troy Verges, Brett Beavers, Brett James, Mac McAnally, and the Warren Brothers[36][37] and formed a lasting working relationship with Liz Rose.[38] They began meeting for two-hour writing sessions every Tuesday afternoon after school.[39] Rose thought the sessions were "some of the easiest I've ever done. Basically, I was just her editor. She'd write about what happened in school that day. She had such a clear vision of what she was trying to say. And she'd come in with the most incredible hooks." Swift became the youngest artist signed by the Sony/ATV Tree publishing house,[40] but left the Sony-owned RCA Records at the age of 14 due to the label's lack of care and them "cut[ting] other people's stuff". She was also concerned that development deals may shelve artists,[32][23] and recalled: "I genuinely felt that I was running out of time. I wanted to capture these years of my life on an album while they still represented what I was going through."[41]

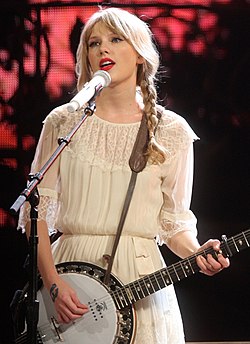

At an industry showcase at Nashville's Bluebird Cafe in 2005, Swift caught the attention of Scott Borchetta, a DreamWorks Records executive who was preparing to form an independent record label, Big Machine Records. She had first met Borchetta in 2004.[43] She was one of Big Machine's first signings,[32] and her father purchased a three-percent stake in the company for an estimated $120,000.[44][45] She began working on her eponymous debut album with producer Nathan Chapman, with whom she felt she had the right "chemistry".[23] Swift wrote three of the album's songs alone, and co-wrote the remaining eight with Rose, Robert Ellis Orrall, Brian Maher, and Angelo Petraglia.[46] Taylor Swift was released on October 24, 2006.[47] Country Weekly critic Chris Neal deemed Swift better than previous aspiring teenage country singers because of her "honesty, intelligence and idealism".[48] The album peaked at number five on the U.S. Billboard 200, where it spent 157 weeks—the longest stay on the chart by any release in the U.S. in the 2000s decade.[49] It made Swift the first female country music artist to write or co-write every track on a U.S. platinum-certified debut album.[50]

Big Machine Records was still in its infancy during the June 2006 release of the lead single, "Tim McGraw", which Swift and her mother helped promote by sending copies of the CD single to country radio stations.[51] As there was not enough furniture at the label yet, they would sit on the floor to do so.[51] She spent much of 2006 promoting Taylor Swift with a radio tour, television appearances; she opened for Rascal Flatts on select dates during their 2006 tour,[52] as a replacement for Eric Church.[53] Borchetta said that although record industry peers initially disapproved of his signing a 15-year-old singer-songwriter, Swift tapped into a previously unknown market—teenage girls who listen to country music.[51][10] Following "Tim McGraw", four more singles were released throughout 2007 and 2008: "Teardrops on My Guitar", "Our Song", "Picture to Burn" and "Should've Said No". All appeared on Billboard's Hot Country Songs, with "Our Song", and "Should've Said No" reaching number one. With "Our Song", Swift became the youngest person to single-handedly write and sing a number-one song on the chart.[54] "Teardrops on My Guitar" reached number thirteen on the U.S. Billboard Hot 100.[55] Swift also released two EPs, The Taylor Swift Holiday Collection in October 2007 and Beautiful Eyes in July 2008.[56][57] She promoted her debut album extensively as the opening act for other country musicians' tours throughout 2006–2007, including George Strait,[58] Brad Paisley,[59] and Tim McGraw and Faith Hill.[60]

Swift won multiple accolades for Taylor Swift. She was one of the recipients of the Nashville Songwriters Association's Songwriter/Artist of the Year in 2007, becoming the youngest person to be honored with the title.[61] She also won the Country Music Association's Horizon Award for Best New Artist,[62] the Academy of Country Music Awards' Top New Female Vocalist,[63] and the American Music Awards' Favorite Country Female Artist honor.[64] She was also nominated for Best New Artist at the 50th Annual Grammy Awards.[65] In 2008, she opened for Rascal Flatts again,[66] and dated singer Joe Jonas for three months.[67][68]

2008–2010: Fearless

[edit]

Swift's second studio album, Fearless, was released on November 11, 2008, in North America,[71] and in March 2009, in other markets.[72] Critics lauded Swift's honest and vulnerable songwriting in contrast to other teenage singers.[73] Five singles were released in 2008 through 2009: "Love Story", "White Horse", "You Belong with Me", "Fifteen", and "Fearless". "Love Story", the lead single, peaked at number four on the Billboard Hot 100 and number one in Australia.[55][74] It was the first country song to top Billboard's Pop Songs chart.[75] "You Belong with Me" was the album's highest-charting single on the Billboard Hot 100, peaking at number two,[76] and was the first country song to top Billboard's all-genre Radio Songs chart.[77] All five singles were Hot Country Songs top-10 entries, with "Love Story" and "You Belong with Me" topping the chart.[78] Fearless became her first number-one album on the Billboard 200 and 2009's top-selling album in the U.S.[79] The Fearless Tour, Swift's first headlining concert tour, grossed over $63 million.[80] Journey to Fearless, a three-part documentary miniseries, aired on television and was later released on DVD and Blu-ray.[81] Swift also performed as a supporting act for Keith Urban's Escape Together World Tour in 2009.[82]

In 2009, the music video for "You Belong with Me" was named Best Female Video at the MTV Video Music Awards.[83] Her acceptance speech was interrupted by rapper Kanye West,[84] an incident that became the subject of controversy, widespread media attention, and many Internet memes.[85] That year she won five American Music Awards, including Artist of the Year and Favorite Country Album.[86] Billboard named her 2009's Artist of the Year.[87] The album ranked number 99 on NPR's 2017 list of the 150 Greatest Albums Made By Women.[88] She won Video of the Year and Female Video of the Year for "Love Story" at the 2009 CMT Music Awards, where she made a parody video of the song with rapper T-Pain called "Thug Story".[89] At the 52nd Annual Grammy Awards, Fearless was named Album of the Year and Best Country Album, and "White Horse" won Best Country Song and Best Female Country Vocal Performance. Swift was the youngest artist to win Album of the Year.Template:NoteTag At the 2009 Country Music Association Awards, Swift won Album of the Year for Fearless and was named Entertainer of the Year, the youngest person to win the honor.[90]

Swift featured on John Mayer's single "Half of My Heart" and Boys Like Girls' single "Two Is Better Than One", the latter of which she co-wrote.[91][92] She co-wrote and recorded "Best Days of Your Life" with Kellie Pickler,[93] and co-wrote two songs for the Hannah Montana: The Movie soundtrack—"You'll Always Find Your Way Back Home" and "Crazier".[70] She contributed two songs to the Valentine's Day soundtrack, including the single "Today Was a Fairytale", which was her first number-one on the Canadian Hot 100, and peaked at number two on the Billboard Hot 100.[94][95] While shooting her film debut Valentine's Day in October 2009, Swift dated co-star Taylor Lautner.[96] In 2009, she made her television debut as a rebellious teenager in an CSI: Crime Scene Investigation episode.[97] She hosted and performed as the musical guest on Saturday Night Live; she was the first host to write their own opening monologue.[98][99]

2010–2014: Speak Now and Red

[edit]

In August 2010, Swift released "Mine", the lead single from her third studio album, Speak Now. It entered the Hot 100 at number three.[100] Swift wrote the album alone and co-produced every track.[101] Speak Now, released on October 25, 2010,[102] debuted atop the Billboard 200 with first-week sales of one million copies.[103] It became the fastest-selling digital album by a female artist, with 278,000 downloads in a week, earning Swift an entry in the 2010 Guinness World Records.[104] Critics appreciated Swift’s grown-up perspectives;[105] Rob Sheffield of Rolling Stone wrote, "in a mere four years, the 20-year-old Nashville firecracker has put her name on three dozen or so of the smartest songs released by anyone in pop, rock or country."[106] The songs "Mine", "Back to December", "Mean", "The Story of Us", "Sparks Fly", and "Ours" were released as singles, with the latter two reaching number one.[78] "Back to December" and "Mean" peaked in the top ten in Canada.[95] She briefly dated actor Jake Gyllenhaal in 2010.[107]

At the 54th Annual Grammy Awards in 2012, Swift won Best Country Song and Best Country Solo Performance for "Mean", which she performed during the ceremony.[108] Swift won other awards for Speak Now, including Songwriter/Artist of the Year by the Nashville Songwriters Association (2010 and 2011),[109][110] Woman of the Year by Billboard (2011),[111] and Entertainer of the Year by the Academy of Country Music (2011 and 2012)[112] and the Country Music Association in 2011.[113] At the American Music Awards of 2011, Swift won Artist of the Year and Favorite Country Album.[114] Rolling Stone placed Speak Now at number 45 in its 2012 list of the "50 Best Female Albums of All Time", writing: "She might get played on the country station, but she's one of the few genuine rock stars we've got these days, with a flawless ear for what makes a song click."[115]

The Speak Now World Tour ran from February 2011 to March 2012 and grossed over $123 million,[116] followed up with its live album, Speak Now World Tour: Live.[117] She contributed two original songs to The Hunger Games soundtrack album: "Safe & Sound", co-written and recorded with the Civil Wars and T-Bone Burnett, and "Eyes Open". "Safe & Sound" won the Grammy Award for Best Song Written for Visual Media and was nominated for the Golden Globe Award for Best Original Song.[118][119] Swift featured on B.o.B's single "Both of Us", released in May 2012.[120] Swift dated Conor Kennedy that year.[121]

In August 2012, Swift released "We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together", the lead single from her fourth studio album, Red. It became her first number one in the U.S. and New Zealand,[122][123] and reached the top slot on iTunes' digital song sales chart 50 minutes after its release, earning the Fastest Selling Single in Digital History Guinness World Record.[124] Other singles released from the album include "Begin Again", "I Knew You Were Trouble", "22", "Everything Has Changed", "The Last Time", and "Red". "I Knew You Were Trouble" reached the top five on charts in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Ireland, New Zealand, the U.K. and the U.S.[125] Three singles, "Begin Again", "22", and "Red", reached the top 20 in the U.S.[55] Red was released on October 22, 2012.[126] On Red, Swift worked with longtime collaborators Nathan Chapman and Liz Rose, as well as new producers such as Max Martin and Shellback.[127] The album incorporated many pop and rock styles such as heartland rock, dubstep and dance-pop.[128] Randall Roberts of Los Angeles Times said Swift "strives for something much more grand and accomplished" with Red.[129] It debuted at number one on the Billboard 200 with first-week sales of 1.21 million copies, making Swift the first female to have two million-selling album openings—a Guinness World Records.[130][131] Red was Swift's first number-one album in the U.K.[132]

The Red Tour ran from March 2013 to June 2014 and grossed over $150 million, becoming the highest-grossing country tour when it completed.[133] The album earned several accolades, including four nominations at the 56th Annual Grammy Awards (2014).[134] Its single "I Knew You Were Trouble" won Best Female Video at the 2013 MTV Video Music Awards.[135] Swift received American Music Awards for Best Female Country Artist in 2012, and Artist of the Year in 2013.[136][137] She received the Nashville Songwriters Association's Songwriter/Artist Award for the fifth and sixth consecutive years in 2012 and 2013.[138] Swift was honored by the Association with the Pinnacle Award, making her the second recipient of the accolade after Garth Brooks.[139] During this time, she briefly dated English singer Harry Styles.[140]

In 2013, Swift recorded "Sweeter than Fiction", a song she wrote and produced with Jack Antonoff for the One Chance film soundtrack. The song received a Best Original Song nomination at the 71st Golden Globe Awards.[141] She provided guest vocals for Tim McGraw's song "Highway Don't Care", which featured guitar work by Keith Urban.[142] Swift performed "As Tears Go By" with the Rolling Stones in Chicago, Illinois as part of the band's 50 & Counting tour.[143] She joined Florida Georgia Line on stage during their set at the 2013 Country Radio Seminar to sing "Cruise".[144] Swift voiced Audrey in the animated film The Lorax (2012),[145] made a cameo in the sitcom New Girl (2013),[146] and had a supporting role in the dystopian drama film The Giver (2014).[147]

2014–2018: 1989 and Reputation

[edit]

In March 2014, Swift began living in New York City.Template:NoteTag She worked on her fifth studio album, 1989, with producers Jack Antonoff, Max Martin, Shellback, Imogen Heap, Ryan Tedder, and Ali Payami.[148] She promoted the album through various campaigns, including inviting fans, called "Swifties", to secret album-listening sessions for the first time.[149] The album was released on October 27, 2014, and debuted atop the U.S. Billboard 200 with sales of 1.28 million copies in its first week.[150] Its singles "Shake It Off", "Blank Space" and "Bad Blood" reached number one in Australia, Canada and the U.S., the first two making Swift the first woman to replace herself at the Hot 100 top spot;[151] other singles include "Style", "Wildest Dreams", "Out of the Woods" and "New Romantics".[152] The 1989 World Tour ran from May to December 2015 and was the highest-grossing tour of the year with $250 million in total revenue.[153]

Prior to 1989's release, Swift stressed the importance of albums to artists and fans.[154] In November 2014, she removed her entire catalog from Spotify, arguing that the streaming company's ad-supported, free service undermined the premium service, which provides higher royalties for songwriters.[155] In a June 2015 open letter, Swift criticized Apple Music for not offering royalties to artists during the streaming service's free three-month trial period and stated that she would pull 1989 from the catalog.[156] The following day, Apple Inc. announced that it would pay artists during the free trial period,[157] and Swift agreed to let 1989 on the streaming service.[158] Swift's intellectual property rights holding company, TAS Rights Management, filed for 73 trademarks related to Swift and the 1989 era memes.[159] She then returned her entire catalog plus 1989 to Spotify, Amazon Music and Google Play and other digital streaming platforms in June 2017.[160] Swift was named Billboard's Woman of the Year in 2014, becoming the first artist to win the award twice.[161] At the 2014 American Music Awards, Swift received the inaugural Dick Clark Award for Excellence.[162] On her 25th birthday in 2014, the Grammy Museum at L.A. Live opened an exhibit in her honor in Los Angeles that ran until October 4, 2015, and broke museum attendance records.[163][164] In 2015, Swift won the Brit Award for International Female Solo Artist.[165] The video for "Bad Blood" won Video of the Year and Best Collaboration at the 2015 MTV Video Music Awards.[166] Swift was one of eight artists to receive a 50th Anniversary Milestone Award at the 2015 Academy of Country Music Awards.[167] At the 58th Grammy Awards in 2016, 1989 won Album of the Year and Best Pop Vocal Album, and "Bad Blood" won Best Music Video. Swift was the first woman and fifth act overall to win Album of the Year twice as a lead artist.[168]

Swift dated Scottish DJ Calvin Harris from March 2015–June 2016.[169] Prior to their breakup, they co-wrote the song "This Is What You Came For", which features vocals from Barbadian singer Rihanna; Swift was initially credited under the pseudonym Nils Sjöberg.[170] After briefly dating English actor Tom Hiddleston,[171] Swift began dating English actor Joe Alwyn in September 2016.[172][173] She wrote the song "Better Man" for country band Little Big Town;Template:NoteTag it earned Swift an award for Song of the Year at the 51st CMA Awards.[174] Swift and English singer Zayn Malik released a single together, "I Don't Wanna Live Forever", for the soundtrack of the film Fifty Shades Darker (2017). The song reached number two in the U.S.[175] and won Best Collaboration at the 2017 MTV Video Music Awards.[176] In August 2017, Swift successfully sued David Mueller, a former radio jockey for KYGO-FM. Four years earlier, Swift had informed Mueller's bosses that he had sexually assaulted her by groping her at an event. After being fired, Mueller accused Swift of lying and sued her for damages from his loss of employment. Shortly after, Swift counter-sued for sexual assault for nominal damages of only one dollar.[177] The jury rejected Mueller's claims and ruled in favor of Swift.[178]

After a one-year hiatus from public spotlight, Swift cleared her social media accounts[179] and released "Look What You Made Me Do" as the lead single from her sixth album, Reputation.[180] The single was Swift's first U.K. number-one single.[181] It topped charts in Australia, Ireland, New Zealand, and the U.S.[182] Reputation was released on November 10, 2017.[183] It incorporated a heavy electropop sound, along with hip hop, R&B, and EDM influences.[184] Reviewers praised Swift's mature artistry, but some denounced the themes of fame and gossip.[185] The album debuted atop the Billboard 200 with first-week sales of 1.21 million copies. Swift became the first act to have four albums sell one million copies within one week in the U.S.[186] The album topped the charts in the UK, Australia, and Canada,[187] and had sold over 4.5 million copies worldwide as of 2018.[188] It spawned three other international singles, including the U.S. top-five entry "...Ready for It?",[189] and two U.S. top-20 singles—"End Game" (featuring Ed Sheeran and rapper Future) and "Delicate".[152] Swift launched the short-lived The Swift Life mobile app for fans in late 2017.[190] Reputation was nominated for Best Pop Vocal Album at the 61st Annual Grammy Awards in 2019.[191] At the American Music Awards of 2018, Swift won four awards, including Artist of the Year and Favorite Pop/Rock Female Artist. After the 2018 AMAs, Swift garnered a total of 23 awards, becoming the most awarded female musician in AMA history, a record previously held by Whitney Houston.[192] In April 2018, Swift featured on country duo Sugarland's "Babe".Template:NoteTag In support of Reputation, she embarked on her Reputation Stadium Tour from May to November 2018.[193] In the U.S., the tour grossed $266.1 million in box office and sold over two million tickets, breaking many records, the most prominent being the highest-grossing North American concert tour in history. It grossed $345.7 million worldwide.[194] It was followed up with an accompanying concert film on Netflix.[195]

2018–2020: Lover, Folklore, and Evermore

[edit]Template:See also Reputation was Swift's last album with Big Machine. In November 2018, she signed a new deal with the Universal Music Group; her subsequent releases were promoted by Republic Records. Swift said the contract included a provision for her to maintain ownership of her masters. In addition, in the event that Universal sold any part of its stake in Spotify, it agreed to distribute a non-recoupable portion of the proceeds among its artists.[196] Vox called it a huge commitment from Universal, which was "far from assured" until Swift intervened.[197]

Swift released her seventh studio album, Lover, on August 23, 2019.[198] Besides Jack Antonoff, Swift worked with new producers Louis Bell, Frank Dukes, and Joel Little.[199] Lover made Swift the first female artist to have a sixth consecutive album sell more than 500,000 copies in one week in the U.S.[200] Critics commended the album's free-spirited mood and emotional intimacy.[201][202] The lead single, "Me!", peaked at number two on the Hot 100.[203] Other singles from Lover were the U.S. top-10 singles "You Need to Calm Down" and "Lover", and U.S. top-40 single "The Man".[55] Lover was the world's best-selling album by a solo artist of 2019, selling 3.2 million copies.[204] Lover and its singles earned nominations at the 62nd Annual Grammy Awards in 2020.[205] At the 2019 MTV Video Music Awards, "Me!" won Best Visual Effects, and "You Need to Calm Down" won Video of the Year and Video for Good. Swift was the first female and second artist overall to win Video of the Year for a video that they directed.[206]

While promoting Lover, Swift became embroiled in a public dispute with talent manager Scooter Braun and Big Machine over the purchase of the masters of her back catalog.[207] Swift said she had been trying to buy the masters, but Big Machine only allowed her to do so if she exchanged one new album for each older one under another contract, which she refused to do.[207][208] Swift began re-recording her back catalog in November 2020.[209] Besides music, she played Bombalurina in the movie adaptation of Andrew Lloyd Webber's musical Cats (2019), for which she co-wrote and recorded the Golden Globe-nominated original song "Beautiful Ghosts".[210][211] Critics panned the film but praised Swift's performance.[212] The documentary Miss Americana, which chronicled parts of Swift's life and career, premiered at the 2020 Sundance Film Festival and was released on Netflix that January.[213][214] Swift signed a global publishing deal with Universal Music Publishing Group in February 2020 after her 16-year-old contract with Sony/ATV expired.[215]

Amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, Swift released two surprise albums: Folklore on July 24, and Evermore on December 11, 2020.[216][217] Both explore indie folk and alternative rock with a more muted production compared to her previous upbeat pop songs.[218][219] Swift wrote and recorded the albums with producers Jack Antonoff and Aaron Dessner from the National.[220] Alwyn co-wrote and co-produced select songs under the pseudonym William Bowery.[221] The albums garnered widespread critical acclaim. The Guardian and Vox opined that Folklore and Evermore emphasized Swift's work ethic and increased her artistic credibility.[222][223] Three singles supported each of the albums, catering the U.S. mainstream radio, country radio, and triple A radio. The singles, in that order, were "Cardigan", "Betty", and "Exile" from Folklore, and "Willow", "No Body, No Crime", and "Coney Island" from Evermore.[224] Swift became the first artist to debut a U.S. number-one album and a number-one song at the same time with Folklore's "Cardigan" and Evermore's "Willow".[225] Folklore was 2020's best-selling album in the U.S. with 1.2 million copies.[226] It won Album of the Year at the 63rd Annual Grammy Awards, making Swift the first woman to win the award thrice.[227] At the 2020 American Music Awards, Swift won three awards, including Artist of the Year for a record third consecutive time.[228] She was 2020's highest-paid musician in the U.S., and the world's highest-paid solo musician.[229]

2021–present: Re-recordings and Midnights

[edit]

Following the masters dispute, Swift released two re-recorded albums—Fearless (Taylor's Version) and Red (Taylor's Version)—in April and November 2021, respectively; both of them debuted atop the Billboard 200,[230] with the former becoming the first re-recorded album ever to do so.[231] Fearless (Taylor's Version) was preceded by the three tracks: "Love Story (Taylor's Version)", "You All Over Me" with Maren Morris, and "Mr. Perfectly Fine",[232] the first of which made Swift the first act since Dolly Parton to have both the original and the re-recording of a single reach number one on the Hot Country Songs chart.[233] The closing track of Red (Taylor's Version), "All Too Well (10 Minute Version)"—accompanied by the namesake short film directed by Swift—debuted atop the Hot 100, becoming the longest song in history to top the chart.[234] The film was met with critical acclaim for Swift's direction.[235] It won the MTV Video Music Award for Video of the Year—Swift's record third win in the category—and the Grammy Award for Best Music Video.[236][237] Swift was the highest-paid female musician of 2021,[238] and both her 2020 albums and the re-recordings were ranked among the top 10 best-sellers of the year.[239] She was awarded the National Music Publishers' Association's Songwriter Icon Award among others.[240] "Wildest Dreams (Taylor's Version)" and "This Love (Taylor's Version)" were released in 2022,[241][242] followed by "All of the Girls You Loved Before", "If This Was a Movie (Taylor's Version)", "Eyes Open (Taylor's Version)", and "Safe & Sound (Taylor's Version)" featuring Joy Williams and John Paul White in 2023.[243] Speak Now (Taylor's Version), the third album in the re-recording series, is set for release on July 7, 2023.[244]

Beyond her albums, Swift was featured on five songs in 2021–2023: "Renegade" and "Birch" by Big Red Machine,[245] a remix of Haim's "Gasoline"[246] and Sheeran's "The Joker and the Queen",[247] and "The Alcott" by the National.[248] She released "Carolina" as part of the soundtrack of the film Where the Crawdads Sing,[249] and played a brief role in the period comedy Amsterdam.[250] Searchlight Pictures announced a feature film written and directed by Swift.[251]

Swift's tenth studio album, Midnights, was released on October 21, 2022.[252] She experimented with electronica[253] and chill-out music styles on it.[254] Rolling Stone critics dubbed the album an "instant classic".[255][256] Commercially, Billboard described the album as a blockbuster,[257] and CNBC called it Swift's biggest success yet.[258] Breaking records across all formats of music consumption,[259][260] Midnights and its lead single, "Anti-Hero", became Spotify's most-streamed album and song in one day with 185 million and 17.4 million plays,[261][262] and the US' best-selling album and digital song of 2022, respectively.[260] The album debuted atop the Billboard 200 with 1.57 million units, marking Swift's fifth album to open with over one million sales. She tied Barbra Streisand for the most number-one albums among women (11), and became the first artist in history to monopolize the Hot 100's entire top 10.[259] "Lavender Haze", which had peaked at number two, became the second single in November 2022.[263] "Karma" became the third, accompanied by a remix featuring American rapper Ice Spice in May 2023.[264]

In March 2023, Swift embarked on the Eras Tour, which broke the record for most concert tickets ever sold in a single day;[259] however, Ticketmaster was widely castigated for its mishandling of the ticket sale, triggering government investigations into the company.[265] Media outlets reported that Swift and Alwyn had ended their six-year relationship,[266] and that she is dating English singer-songwriter Matty Healy.[267]

Artistry

[edit]Influences

[edit]One of Swift's earliest memories of music is listening to her grandmother, Marjorie Finlay, sing in church.[5] As a child, she enjoyed Disney film soundtracks: "My parents noticed that, once I had run out of words, I would just make up my own."[268] Swift said she owes her confidence to her mother, who helped her prepare for class presentations as a child.[269] She also attributes her "fascination with writing and storytelling" to her mother.[270] Swift was drawn to the storytelling aspect of country music,[271] and was introduced to the genre listening to "the great female country artists" of the 1990s—Shania Twain, Faith Hill, and the Dixie Chicks.[272][273] Twain, both as a songwriter and performer, was her biggest musical influence.[274] Hill was Swift's childhood role model, and she would often imitate her.[275] She admired the Dixie Chicks' defiant attitude and their ability to play their own instruments.[276] Swift also explored the music of older country stars such as Patsy Cline, Loretta Lynn, Tammy Wynette, and Dolly Parton,[22] the last of whom she believes is exemplary to female songwriters,[111] and alt-country artists like Patty Griffin[277] and Lori McKenna.[10] As a songwriter, Swift was influenced by Joni Mitchell, citing especially how Mitchell's autobiographical lyrics convey the deepest emotions: "I think [Blue] is my favorite because it explores somebody's soul so deeply."[278]

Swift has also been influenced by various pop and rock artists. She lists Paul McCartney, Bruce Springsteen, Bryan Adams,[279] the Rolling Stones,[280] Emmylou Harris, Kris Kristofferson, and Carly Simon as her career role models.[10][281] She likes Springsteen and the Stones for remaining musically relevant for a long time[282] and credits the Stones with being "a huge influence on my entire outlook on my career."[283] As she grows older, Swift aspires to be like Harris and prioritize music over fame.[284] Her synth-pop album 1989 was influenced by some of her favorite 1980s pop acts, including Peter Gabriel, Annie Lennox, Phil Collins, and Madonna.[285][286] She has also cited Keith Urban's musical style[287] and Fall Out Boy's lyrics as major influences.[288]

Music style

[edit]"If there's one thing that Swift has proven throughout her career, it's that she refuses to be put in a box. Her ever-evolving sound took her from country darling to pop phenom to folk's newest raconteur."

Swift is known for venturing into various music genres and undergoing artistic reinventions,[290][251] having been described as a "music chameleon".[291][292] She self-identified as a country musician until 2012, when she released her fourth studio album, Red.[293] Her albums were promoted to country radio, but music critics noted wide-ranging styles of pop and rock.Template:Sfnm[294] After 2010, they observed that Swift's melodies are rooted in pop music, and the country music elements are limited to instruments such as banjo, mandolin, and fiddle, and her slight twang;[295][296] some commented that her country music identity was an indicator of her narrative songwriting rather than musical style.[297][298] Although the Nashville music industry was receptive of Swift's status as a country musician, critics accused her of abandoning the legitimate roots of country music in favor of crossover success in the mainstream pop market.[299][300] RedTemplate:'s eclectic pop, rock, and electronic styles intensified the critical debate, to which Swift responded, "I leave the genre labeling to other people."[301]

Music journalist Jody Rosen commented that by originating her musical career in Nashville, Swift made a "bait-and-switch maneuver ... planting roots in loamy country soil, then pivoting to pop".[302] She abandoned her country music identity in 2014 with the release of her synth-pop fifth studio album, 1989. Swift described it as her first "documented, official pop album".[303] Her subsequent albums Reputation (2017) and Lover (2019) have an upbeat pop production; the former incorporates hip hop, trap, and EDM elements.[304][305][306] Midnights (2022), on the other hand, is distinguished by a more experimental, "subdued and amorphous pop sound".[307][308] Although reviews of Swift's pop albums were generally positive, some critics lamented that the pop music production indicated Swift's pursuit of mainstream success, eroding her authenticity as a songwriter nurtured by her country music background—a criticism that has been retrospectively described as rockist.[309]Template:Sfnm Musicologist Nate Sloan remarked that Swift's pop music transition was rather motivated by her need to expand her artistry.[310] Swift eschewed mainstream pop in favor of alternative styles like indie rock with her 2020 studio albums Folklore and Evermore.[311][312] Clash said her career "has always been one of transcendence and covert boundary-pushing", reaching a point at which "Taylor Swift is just Taylor Swift", not defined by any genre.[313]

Voice

[edit]Swift possesses a mezzo-soprano vocal range,[314] and a generally soft but versatile timbre.[315][316] As a country singer, her vocals were criticized by some as weak and strained compared to those of her contemporaries.[317] Swift admitted her vocal ability often concerned her in her early career and has worked hard to improve.[318] Reviews of her vocals remained mixed after she transitioned to pop music with 1989; critics complained that she lacked proper technique but appreciated her usage of her voice to communicate her feelings to the audience, prioritizing "intimacy over power and nuance".[319] They also praised her for refraining from correcting her pitch with Auto-Tune.[320] Los Angeles Times remarked that Swift's defining vocal feature is her attention to detail to convey an exact feeling—"the line that slides down like a contented sigh or up like a raised eyebrow".[321] With Reputation, critics noted that she was "learning how to use her voice as a percussion instrument of its own",[322] swapping her "signature expressiveness" for cadences and rhythms that are "cool, conversational, detached" and reminiscent of hip hop and R&B styles.[323][324][325]

Reviews of Swift's later albums and performances were more appreciative of her vocals, finding them less nasal, richer, more resonant, and more powerful.[296][326][327] With Folklore and Evermore, Swift received praise for her sharp and agile yet translucent and controlled voice.[328][329][330] Pitchfork described her vocals on the albums as "versatile and expressive".[331] Music theory professor Alyssa Barna called Swift's timbre "breathy and bright" in the upper register and "full and dark" in the lower.[219] With her 2021 re-recorded albums, critics began to praise the mature, deeper and "fuller" tone of her voice.[332][333][334] An i review said Swift's voice is "leagues better now" with her newfound vocal furniture.[335] The Guardian highlighted "yo-yoing vocal yelps" and passionate climaxes as the trademarks of Swift's voice,[336] and that her country twang faded away.[337] Midnights received acclaim for Swift's nuanced vocal delivery.[338] She ranked 102nd on the 2023 Rolling Stone list of the 200 Greatest Singers of All Time.[316]

Songwriting

[edit]Swift has been referred to as one of the greatest songwriters of all time by several publications.[339][340][341] She told The New Yorker in 2011 that she identifies as a songwriter first: "I write songs, and my voice is just a way to get those lyrics across".[10] Swift's personal experiences were a common inspiration for her early songs, which helped her navigate life.[342][343] Her "diaristic" technique began with identifying an emotion, followed by a corresponding melody.[344][345] On her first three studio albums, love, heartbreak, and insecurities, from an adolescent perspective, were dominant themes.[346][347] She delved into the tumult of toxic relationships on Red,[348] and embraced nostalgia and post-romance positivity on 1989.[285] Reputation was inspired by the downsides of Swift's fame,[349] and Lover detailed her realization of the "full spectrum of love".[350] Other themes in Swift's music include family dynamics, friendship,[351][352] alienation, self-awareness, and tackling vitriol, especially sexism.[270][353]

Her confessional lyrics received positive reviews from critics;[354][10][355] they highlighted its vivid details and emotional engagement, which they found uncommon in pop music.[356][357][358] Critics praised her melodic songwriting; Rolling Stone described Swift as "a songwriting savant with an intuitive gift for verse-chorus-bridge architecture".[359][360] NPR dubbed Swift "a master of the vernacular in her lyrics",[324] remarking that her songs offer emotional engagement because "the wit and clarity of her arrangements turn them from standard fare to heartfelt disclosures".[360] Despite the positive reception, The New Yorker stated she was generally portrayed "more as a skilled technician than as a Dylanesque visionary".[10] Tabloid media often speculated and linked the subjects of her songs with her ex-lovers, a practice reviewers and Swift herself criticized as sexist.[361][362][363] Aside from clues in album liner notes, Swift avoided talking about the subjects of her songs.[364]

On her 2020 albums Folklore and Evermore, Swift was inspired by escapism and romanticism to explore fictional narratives.[365] Without referencing her personal life, she imposed emotions onto imagined characters and story arcs, which liberated her from tabloid attention and suggested new paths for her artistry.[344] Swift explained that she welcomed the new songwriting direction after she stopped worrying about commercial success.[365] According to Spin, she explored complex emotions with "precision and devastation" on Evermore.[366] Consequence stated her 2020 albums provided a chance to convince skeptics of Swift had "songwriting power", noting her transformation from "teenage wunderkind to a confident and careful adult".[367]

Swift self-categorizes her songwriting into three types: "quill lyrics", referring to songs rooted in antiquated poeticism; "fountain pen lyrics", based on modern and vivid storylines; and "glitter gel pen lyrics"—lively and frivolous.[368] Critics note the fifth track of every Swift album as the most "emotionally vulnerable" song of the album.[369] Swift's bridges are often underscored as one of the best aspects of her songs,[370][367] earning her the title "Queen of Bridges" from Time.[371] Awarding her with the Songwriter Icon Award in 2021, the National Music Publishers' Association remarked that "no one is more influential when it comes to writing music today" than Swift.[372] The Week deemed her the foremost female songwriter of modern times,[373] and the Nashville Songwriters Association International named her Songwriter-Artist of the Decade in 2022.[259] Carole King considers Swift her "professional grand daughter" and thanked Swift for "carrying the torch forward".[374] Swift has also published two original poems: "Why She Disappeared" and "If You're Anything Like Me".[375]

Video and film

[edit]Swift emphasizes visuals as a key creative component of her music making process.[376] She has collaborated with different directors to produce her music videos, and over time she has become more involved with writing and directing. She developed the concept and treatment for "Mean" in 2011[377] and co-directed the music video for "Mine" with Roman White the year before.[378] In an interview, White said that Swift "was keenly involved in writing the treatment, casting and wardrobe. And she stayed for both the 15-hour shooting days, even when she wasn't in the scenes."[379]

From 2014 to 2018, Swift collaborated with director Joseph Kahn on eight music videos—four each from her albums 1989 and Reputation. Kahn has praised Swift's involvement in the craft.[380] She worked with American Express for the "Blank Space" music video (which Kahn directed), and served as an executive producer for the interactive app AMEX Unstaged: Taylor Swift Experience, for which she won a Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Interactive Program in 2015.[381] Swift produced the music video for "Bad Blood" and won a Grammy Award for Best Music Video in 2016.[382]

Her production house, Taylor Swift Productions, Inc., is credited with producing all of her visual media starting with her 2018 concert documentary Reputation Stadium Tour.[383] She continued to co-direct music videos for the Lover singles "Me!" with Dave Meyers, and "You Need to Calm Down" (also serving as a co-executive producer) and "Lover" with Drew Kirsch,[384] but also ventured into sole direction with the videos for "The Man" (which won her the MTV Video Music Award for Best Direction), "Cardigan", "Willow", "Anti-Hero" and "Bejeweled".[385] After Folklore: The Long Pond Studio Sessions, Swift debuted as a filmmaker with All Too Well: The Short Film,[259] which made her the first artist to win the Grammy Award for Best Music Video as a sole director.[386] Swift has cited Chloé Zhao, Greta Gerwig, Nora Ephron, Guillermo del Toro, John Cassavetes, and Noah Baumbach as her filmmaking influences.[376]

Accolades and achievements

[edit]

Swift has won 12 Grammy Awards (including three for Album of the Year—tying for the most by an artist),[387] an Emmy Award,[388] 40 American Music Awards (the most won by an artist),[389] 29 Billboard Music Awards (the most won by a woman),[390] 92 Guinness World Records,[391] 14 MTV Video Music Awards (including three Video of the Year wins—the most by an act),[236] 12 Country Music Association Awards (including the Pinnacle Award),[392] eight Academy of Country Music Awards,[393] and two Brit Awards.[165] As a songwriter, she has been honored by the Nashville Songwriters Association,[61][394] the Songwriters Hall of Fame, and the National Music Publishers' Association and was the youngest person on Rolling StoneTemplate:'s list of the 100 Greatest Songwriters of All Time in 2015.[395][396] At the 64th BMI Awards in 2016, Swift was the first woman to be honored with an award named after its recipient.[397]

From available data, Swift has amassed over 50 million album sales, 150 million single sales,[398][399][400] and 114 million units globally, including 78 billion streams.[401][402] The International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI) ranked her as the Global Recording Artist of the Year for a record three times (2014, 2019 and 2022).[403] Swift has the most number-one albums in the United Kingdom and Ireland for a female artist this millennium,[404][405] and earned the highest income for an artist on Chinese digital music platforms—Template:Currency.[406] Swift is the most streamed female act on Spotify,[407] and the only artist to have received more than 200 million streams in one day (228 million streams on October 21, 2022).[408] The most entries and the most simultaneous entries for an artist on the Billboard Global 200, with 94 and 31 songs, respectively, are among her feats.[409][410] Her Reputation Stadium Tour (2018) is the highest-grossing North American tour ever,[411] and she was the world's highest-grossing female touring act of the 2010s.[412] Beginning with Fearless, all of her studio albums opened with over a million global units.[413]

In the US, Swift has sold over 37.3 million albums as of 2019,[400] when Billboard placed her eighth on its Greatest of All Time Artists Chart.[414] Nine of her songs have topped the Billboard Hot 100. She is the longest-reigning act of Billboard Artist 100 (64 weeks),[415] the soloist with the most cumulative weeks (56) atop the Billboard 200,[407] the woman with the most Hot 100 entries (189),[416] top-ten songs (40),[417] and weeks atop the Top Country Albums (98),[418] and the act with the most Digital Songs number-ones (23).[419][420] Swift is the second highest-certified female digital singles artist (and third overall) in the U.S., with 134 million total units certified by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA),[421] and the first woman to have both an album (Fearless) and a song ("Shake It Off") certified Diamond.[422]

Swift has appeared in various power listings. Time included her on its annual list of the 100 most influential people in 2010, 2015, and 2019.[423] She was one of the "Silence Breakers" honored as Time Person of the Year in 2017 for speaking up about sexual assault.[424] In 2014, she was named to Forbes' 30 Under 30 list in the music category[425] and again in 2017 in its "All-Star Alumni" category.[426] Swift became the youngest woman to be included on Forbes' list of the 100 most powerful women in 2015, ranked at number 64.[427] Swift received an honorary Doctor of Fine Arts degree from New York University and served as its commencement speaker on May 18, 2022.[259]

Cultural status

[edit]

As one of the leading music artists of the 21st century, Swift has influenced the music industry in many aspects.[428] Publications describe Swift as a cultural "vitality" or zeitgeist,[429][430] with Billboard noting only few artists have had her chart success, critical acclaim, and fan support, resulting in her wide impact.[431] Publications consider Swift's million-selling albums an anomaly in the streaming-dominated industry following the end of the album era in the 2010s.[432][433] Swift is the only artist in Luminate Data history to have five albums sell over a million copies in a week,[434] proving she is "the one bending the music industry to her will" to New York magazine.[433] Swift is also regarded as a champion of independent record shops,[435][436] contributing to the 21st-century vinyl revival.[437][438] Variety dubbed Swift the "Queen of Stream" after she achieved multiple streaming feats.[439] Economist Alan Krueger devised his concept "rockonomics"—a microeconomic analysis of the music industry—using Swift, whom he considers an "economic genius".[440]

New York magazine's Jody Rosen dubbed Swift the "world's biggest pop star", and opined that the trajectory of her stardom has defied established patterns: "[Swift] falls between genres, eras, demographics, paradigms, trends", leaving all the other artists such as Beyoncé, Rihanna, Lady Gaga, Katy Perry, Miley Cyrus, and Justin Bieber "all vying for second place".[302] According to CNN, Swift began the 2010s decade as a country star and ended it as an "all-time musical titan".[441] She was the most googled woman in 2019 and musician in 2022.[442][443]

Legacy

[edit]Swift helped shape the modern country music scene,[444] having extended her success and fame beyond the U.S.,[302][444] pioneered the use of internet (Myspace) as a marketing tool,[32][51] and introduced the genre to a younger generation.[445][302] Country labels have since become interested in signing young singers who write their own music;[446] her guitar performances contributed to the "Taylor Swift factor", a phenomenon to which upsurge in guitar sales to women, a previously ignored demographic, is attributed.[447][448] According to publications, Swift changed the contemporary music landscape "forever" with the genre transitions across her career, a discography that accommodates cultural shifts,[449] and her power "to pull any sound she wants into mainstream orbit".[450] Furthermore, in being personal and vulnerable in her lyrics, music journalist Nick Catucci opined Swift helped make space for later pop stars like Billie Eilish, Ariana Grande, and Halsey to do the same.[451] Scholars have also highlighted the literary sensibility and poptimist implications of Swift and her music in the 21st century.[452][453]

Swift has influenced numerous music artists, and her albums have inspired an entire generation of singer-songwriters.[445][311][454] Journalists praise her ability to change industry practices, noting how her actions reformed policies of streaming platforms, prompted awareness of intellectual property among upcoming musicians,[455][456] and reshaped the concert ticketing model.[457] Various sources deem Swift's music a paradigm representing the millennial generation;[458] Vox called her the "millennial Bruce Springsteen",[459] and The Times named her "the Bob Dylan of our age".[460] In recognition of her cultural impact, Swift earned the title Woman of the Decade (2010s) from Billboard,[461] Artist of the Decade (2010s) at the American Music Awards,[462] and Global Icon at the Brit Awards.[402]

Swift is also a subject of academic study;[463] her artistry and fame are popular topics of scholarly media research.[290] Various educational institutions offer courses on Swift in literary, cultural and sociopolitical contexts.[464][290] Her songs are studied by evolutionary psychologists and cultural analysts to understand the relationship between popular music and human mating strategies.[465][466] Entomologists named a millipede species Nannaria swiftae in her honor.[252]

Public image

[edit]Swift's music, life and image are points of attention in the global celebrity culture.[290] She started as a teen idol,[467] and has become a dominant figure in popular culture,[468] often referred to as a pop icon.[304][469] Publications note her immense popularity and longevity as the kind of fame unwitnessed since the 20th century.[470][471] Music critics Sam Sanders and Ann Powers regard Swift as a "surprisingly successful composite of megawatt pop star and bedroom singer-songwriter."[472]

Journalists have written about Swift's polite and "open" personality,[35][44] calling her a "media darling" and "a reporter's dream".[354] Awarding her for her humanitarian endeavors in 2012, former First Lady Michelle Obama described Swift as an artist who "has rocketed to the top of the music industry but still keeps her feet on the ground, someone who has shattered every expectation of what a 22-year-old can accomplish".[473] Swift was labeled by the media in her early career as "America's Sweetheart" for her likability and girl-next-door image.[474][475] YouGov surveys ranked her as the world's most admired female musician from 2019 to 2021.[476]

Though Swift is reluctant to publicly discuss her personal life, believing it to be "a career weakness",[477] it is a topic of widespread media attention and tabloid speculation,[478] with all her moves "closely monitored and analyzed."[430] Clash described Swift as a lightning rod for both praise and criticism.[479] The New York Times asserted in 2013 that her "dating history has begun to stir what feels like the beginning of a backlash" and questioned whether she was in the midst of a "quarter-life crisis".[480] Critics have highlighted that Swift's life and career have been subject to intense misogyny and slut-shaming.[481][482] Glamour opined Swift is an easy target for male derision, triggering "fragile male egos".[483] The Daily Telegraph said her antennae for sexism are crucial for the industry.[484]

Swift is known for her love of cats. Her pet cats have been featured in her visual works,[485] and one of them is the third richest pet animal in the world, with an estimated net worth of $97 million.[486]

Entrepreneurship

[edit]Media outlets describe Swift as a savvy businesswoman.[487][488] She is also known for her traditional album rollouts, consisting of a variety of promotional activities that Rolling Stone termed as an inescapable "multimedia bonanza".[489][490] Easter eggs and cryptic teasers became a common practice in contemporary pop music because of Swift.[491] Publications describe her discography as a music "universe" subject to analyses by fans, critics and journalists.[492][493][468] Swift maintains an active presence on social media and a close relationship with fans, to which many journalists attribute her success.[494][428][495]

Swift has endorsed many brands and businesses. In 2009, she launched a l.e.i. sundress range at Walmart,[496] and designed American Greetings cards and Jakks Pacific dolls.[497][498] Also that year, she became a spokesperson for the National Hockey League's Nashville Predators and Sony Cyber-shot digital cameras.[499][500] Swift launched two Elizabeth Arden fragrances—"Wonderstruck" and "Wonderstruck Enchanted",[501] followed by "Taylor" and its "Made of Starlight" variation in 2013,[502][503] and "Incredible Things" in 2014.[504] She signed a multi-year deal with AT&T in 2016 and bank corporation Capital One in 2019.[505][506] Swift released a sustainable clothing line with Stella McCartney in 2019.[507] In light of her philanthropic support for independent record stores during the COVID-19 pandemic, Record Store Day named Swift their first-ever global ambassador.[435] Swift has refused to invest in cryptocurrency and "unregistered securities".[508][509]

Politics

[edit]Swift identifies as a pro-choice[510] feminist, and is one of the founding signatories of the Time's Up movement against sexual harassment.[511] She criticized the US Supreme Court's decision to overturn Roe v. Wade (1973) and end federal abortion rights in 2022.[512] Swift advocates for LGBT rights,[513] and has called for the passing of the Equality Act, which prohibits discrimination based on sex, sexual orientation, and gender identity.[514][515] The New York Times wrote her 2011 music video for "Mean" had a positive impact on the LGBTQ+ community.[516] Swift performed during WorldPride NYC 2019 at the Stonewall Inn, a gay rights monument.[517] She has donated to the LGBT organizations Tennessee Equality Project and GLAAD.[518][519]

A supporter of the March for Our Lives movement and gun control reform in the U.S.,[520] Swift is a vocal critic of white supremacy, racism, and police brutality.[521][510] In 2020, she urged her fans to check their voter registration ahead of elections, which resulted in 65,000 people registering to vote within a day after her post,[522] and then endorsed Joe Biden and Kamala Harris in the U.S. presidential election.[523] In the wake of the George Floyd protests, she donated to the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund and the Black Lives Matter movement,[524] called for the removal of Confederate monuments in Tennessee,[525] and advocated for Juneteenth to become a national holiday.[526]

Wealth and philanthropy

[edit]Swift's net worth is $570 million, per a 2022 estimate by Forbes. Additionally, her publication rights over her first six albums are valued at $200 million.[527] Forbes has named her the annual top-earning female musician four times (2016, 2019, 2021, and 2022).[528] She was the highest-paid celebrity of 2016 with $170 million—a feat recognized by the Guinness World Records as the highest annual earnings ever for a female musician,[529] which she herself surpassed with $185 million in 2019.[530] Overall, Swift was the highest paid female artist of the 2010s decade, earning $825 million.[531] She has invested in a real estate portfolio worth $84 million,[532] including the Samuel Goldwyn Estate in Beverly Hills, California;[532] the High Watch in Watch Hill, Rhode Island;[533] and multiple adjacent purchases in Tribeca, Manhattan, nicknamed as "Taybeca" by local realtors.[534]

Swift is well known for her philanthropic efforts.[535] She was ranked at number one on DoSomething's "Gone Good" list,[536] and has received the "Star of Compassion" accolade from the Tennessee Disaster Services,[537] The Big Help Award from the Nickelodeon Kids' Choice Awards for her "dedication to helping others" as well as "inspiring others through action".[538] In 2008, she donated $100,000 to the Red Cross to help the victims of the Iowa flood.[539] Swift has performed at charity relief events, including Sydney's Sound Relief concert.[540] In response to the May 2010 Tennessee floods, Swift donated $500,000 during a telethon hosted by WSMV.[541] In 2011, Swift used a dress rehearsal of her Speak Now tour as a benefit concert for victims of recent tornadoes in the U.S., raising more than $750,000.[542] In 2016, she donated $1 million to Louisiana flood relief efforts and $100,000 to the Dolly Parton Fire Fund.[543][544] Swift donated to food banks after Hurricane Harvey struck Houston in 2017 and to various cities during the Eras Tour in 2023.[545][546] In 2020, she donated $1 million for Tennessee tornado relief.[547]

Swift is a supporter of the arts. She is a benefactor of the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame.[548] She has donated $75,000 to Nashville's Hendersonville High School to help refurbish the school auditorium,[549] $4 million to fund the building of a new education center at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum in Nashville,[550] $60,000 to the music departments of six U.S. colleges,[551] and $100,000 to the Nashville Symphony.[552] Also a promoter of children's literacy, she has donated money and books to various schools around the country to improve education.[553][554] In 2007, Swift partnered with the Tennessee Association of Chiefs of Police to launch a campaign to protect children from online predators.[555] She has donated items to several charities for auction, including the UNICEF Tap Project and MusiCares.[556] As recipient of the Academy of Country Music's Entertainer of the Year in 2011, Swift donated $25,000 to St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, Tennessee.[557] In 2012, Swift participated in the Stand Up to Cancer telethon, performing the charity single "Ronan", which she wrote in memory of a four-year-old boy who died of neuroblastoma.[558] She has also donated $100,000 to the V Foundation for Cancer Research[559] and $50,000 to the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia.[560] Swift has encouraged young people to volunteer in their local communities as part of Global Youth Service Day.[561]

Swift donated to fellow singer-songwriter Kesha to help with her legal battles against Dr. Luke[535] and to actress Mariska Hargitay's Joyful Heart Foundation organization.[562] After the COVID-19 pandemic began, Swift donated to the World Health Organization and Feeding America[563] and offered one of her signed guitars as part of an auction to raise money for the National Health Service.[564] Swift performed "Soon You'll Get Better" during the One World: Together At Home television special, a benefit concert curated by Lady Gaga for Global Citizen to raise funds for the World Health Organization's COVID-19 Solidarity Response Fund.[565] In 2018 and 2021, Swift donated to the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network in honor of Sexual Assault Awareness and Prevention Month.[535][566] In addition to charitable causes, she has made donations to her fans several times for their medical or academic expenses.[567]

Discography

[edit]

Studio albums[edit]

|

Re-recorded albums[edit]

|

Filmography

[edit]- Hannah Montana: The Movie (2009)

- Valentine's Day (2010)

- Journey to Fearless (2010)

- The Lorax (2012)

- The Giver (2014)

- The 1989 World Tour Live (2015)

- Taylor Swift: Reputation Stadium Tour (2018)

- Cats (2019)

- Miss Americana (2020)

- City of Lover (2020)

- Folklore: The Long Pond Studio Sessions (2020)

- All Too Well: The Short Film (2021)

- Amsterdam (2022)

Tours

[edit]- Fearless Tour (2009–2010)

- Speak Now World Tour (2011–2012)

- The Red Tour (2013–2014)

- The 1989 World Tour (2015)

- Reputation Stadium Tour (2018)

- The Eras Tour (2023)

See also

[edit]- List of best-selling female music artists

- List of Grammy Award winners and nominees by country

- List of highest-certified music artists in the United States

- List of most-followed Instagram accounts

- List of most-followed Twitter accounts

- List of most-subscribed YouTube channels

Footnotes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "What Is Taylor Swift's Pseudonym And When Does She Use It? The Pop Sensation's Alias Explained". CapitalFM. May 26, 2020. Retrieved March 26, 2023.

- ^ "Taylor Swift: The record-breaking artist in numbers". Newsround. March 2, 2020. Archived from the original on March 8, 2020. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- ^ Sutherland, Mark (May 23, 2015). "Taylor Swift interview: 'A relationship? No one's going to sign up for this'". The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on January 10, 2022. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- ^ "Taylor Swift is not an "underdog": The real story about her 1 percent upbringing that the New York Times won't tell you". Salon. May 23, 2015. Retrieved December 26, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jepson 2013, p. 1.

- ^ Roth, Madeline (May 19, 2015). "Taylor Swift's Brother Had The Most Epic Graduation Weekend Ever". MTV News. Archived from the original on July 23, 2016. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- ^ Scott, Walter (June 11, 2015). "What Famous Pop Star Is Named After James Taylor?". Parade. Archived from the original on October 15, 2016. Retrieved December 12, 2018.

- ^ Eleftheriou-Smith, Loulla-Mae (June 24, 2015). "Taylor Swift tells Scotland: 'I am one of you'". The Independent. Archived from the original on May 26, 2022. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- ^ "Taylor Swift stammt aus dem Freistaat". BR24 (in German). September 17, 2015. Retrieved August 27, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Widdicombe, Lizzie (October 10, 2011). "You Belong With Me". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on July 24, 2014. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ Raab, Scott (October 20, 2014). "Taylor Swift Interview". Esquire. Archived from the original on February 16, 2015. Retrieved April 11, 2015.

- ^ "Taylor Swift on Politicians Co-opting Faith: 'I'm a Christian. That's Not What We Stand For'". Relevant. January 31, 2020. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ Uhrich, Bill (February 13, 2010). "Photos Students at Alvernia Montessori School sending Taylor Swift a valentine". Reading Eagle. Archived from the original on October 16, 2013. Retrieved February 25, 2013.

- ^ Hatza, George (December 8, 2008). "Taylor Swift: Growing into superstardom". Reading Eagle. Archived from the original on April 1, 2012. Retrieved April 17, 2012.

- ^ Mennen, Lauren (November 12, 2014). "Taylor Swift's Wyomissing childhood home on the market for $799,500". Philadelphia Daily News. Archived from the original on October 17, 2016. Retrieved October 13, 2016.

- ^ Chang, David (February 22, 2016). "Taylor Swift Returns to Reading Pennsylvania as Maid of Honor in Friend's Wedding". WCAU. Archived from the original on September 16, 2016. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

- ^ Qureshi, Hira. "Visit this Stone Harbor café where Taylor Swift was 'always coming in to play' as a child". courierpostonline.com. courierpostonline.com. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ^ Kuperinsky, Amy (July 28, 2020). "Taylor Swift shouts out Jersey Shore town in video for surprise album". NJ.com. Advance Local Media, LLC. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ^ "Taylor Swift, Age 12". Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on August 27, 2016. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

- ^ Cooper, Brittany Joy (April 15, 2012). "Taylor Swift Opens Up About a Future in Acting and Admiration for Emma Stone". Taste of Country. Archived from the original on April 17, 2012. Retrieved April 17, 2012.

- ^ MacPherson, Alex (October 18, 2012). "Taylor Swift: 'I want to believe in pretty lies'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 26, 2016. Retrieved August 3, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rolling Stone Interview: The Unabridged Taylor Swift, December 2, 2008

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Morris, Edward (December 1, 2006). "When She Thinks 'Tim McGraw', Taylor Swift Savors Payoff: Hardworking Teen to Open for George Strait Next Year". CMT. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved March 11, 2010.

- ^ Diu, Nisha Lilia (April 3, 2011). "Taylor Swift: 'I won't do sexy shoots'". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on May 6, 2013. Retrieved April 17, 2012.

- ^ "News : CMT Insider Interview: Taylor Swift (Part 1 of 2)". CMT. November 26, 2008. Archived from the original on January 23, 2015. Retrieved July 1, 2012.

- ^ Malec, Jim (May 2, 2011). "Taylor Swift: The Garden In The Machine". American Songwriter. Archived from the original on May 10, 2012. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ Martino, Andy (January 10, 2015). "EXCLUSIVE: The real story of Taylor Swift's guitar 'legend'". Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on November 22, 2015. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- ^ The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon (October 4, 2019). "Name That Song Challenge with Taylor Swift (timestamp: 3:35)". Archived from the original on October 29, 2021. Retrieved May 24, 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ "americanbar.org PDF" (PDF). Americanbar.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 11, 2012. Retrieved April 18, 2012.

- ^ "On tour with Taylor Swift – Dateline NBC". NBC News. May 31, 2009. Archived from the original on October 5, 2013. Retrieved July 1, 2012.

- ^ Castro, Vicky (February 6, 2015). "How to Succeed as an Entrepreneur, Taylor Swift Style". Inc. Monsueto Ventures. Archived from the original on June 7, 2016. Retrieved February 9, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Willman, Chris (July 25, 2007). "Getting to know Taylor Swift". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved January 25, 2022.

- ^ Jo, Nancy (January 2, 2014). "Taylor Swift and the Growing of a Superstar: Her Men, Her Moods, Her Music". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on November 10, 2015. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- ^ "News : Taylor Swift's High School Names Auditorium in Her Honor". CMT. September 23, 2010. Archived from the original on November 21, 2014. Retrieved April 18, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Grigoriadis, Vanessa (March 5, 2009). "The Very Pink, Very Perfect Life of Taylor Swift". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on May 3, 2019. Retrieved July 28, 2019.

- ^ "Taylor Swift: The Garden In The Machine". American Songwriter. May 2, 2011. Archived from the original on August 7, 2013. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ "Songwriter Taylor Swift Signs Publishing Deal With Sony/ATV". Broadcast Music, Inc. May 12, 2005. Archived from the original on December 4, 2012. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- ^ Kosser, Michael (June 3, 2010). "Liz Rose: Co-Writer to the Stars". American Songwriter. Archived from the original on December 24, 2011. Retrieved April 19, 2012.

- ^ Leahey, Andrew (October 24, 2014). "Songwriter Spotlight: Liz Rose". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on September 26, 2016. Retrieved September 24, 2016.

- ^ DeLuca, Dan (November 11, 2008). "Focused on 'great songs' Taylor Swift isn't thinking about 'the next level' or Joe Jon as gossip". Philadelphia Daily News. p. 1. Archived from the original on November 18, 2012. Retrieved April 17, 2012.

- ^ Preston, John (April 26, 2009). "Taylor Swift: the 19-year-old country music star conquering America – and now Britain". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 5, 2012. Retrieved August 30, 2012.

- ^ Rosa, Christopher (March 24, 2015). "Opening Acts Who Became Bigger Than The Headliner". VH1. Archived from the original on November 10, 2015. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- ^ Rapkin, Mickey (July 27, 2017). "Oral History of Nashville's Bluebird Cafe: Taylor Swift, Maren Morris, Dierks Bentley & More on the Legendary Venue". Billboard. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved July 28, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hiatt, Brian (October 25, 2012). "Taylor Swift in Wonderland". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on July 31, 2016. Retrieved August 1, 2016.

- ^ Greenburg, Zack O'Malley (June 26, 2013). "Toby Keith, Cowboy Capitalist: Country's $500 Million Man". Forbes. Archived from the original on August 27, 2016. Retrieved August 1, 2016.

- ^ Template:Cite AV media notes

- ^ Tamarkin, Jeff. "Taylor Swift – Taylor Swift". AllMusic. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ^ Neal, Chris (December 4, 2006). "Taylor Swift Review". Country Weekly. Archived from the original on July 22, 2012. Retrieved March 31, 2010.

- ^ Trust, Gary (October 29, 2009). "Chart Beat Thursday: Taylor Swift, Tim McGraw Linked Again". Billboard. Archived from the original on March 7, 2013. Retrieved November 8, 2016.

- ^ "Taylor Swift". Songwriters' Hall of Fame. Retrieved September 21, 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Willman, Chris (February 5, 2008). "Taylor Swift's Road to Fame". Entertainment Weekly. p. 3. Archived from the original on February 21, 2015. Retrieved April 22, 2012.

- ^ "Taylor Swift Joins Rascal Flatts Tour". CMT. October 18, 2006. Archived from the original on January 7, 2015. Retrieved March 11, 2010.

- ^ Whitaker, Sterling; Hammar, Ania (May 27, 2019). "How Eric Church's Rascal Flatts Feud Helped Launch Taylor Swift's Career". Taste of Country. Archived from the original on June 6, 2019. Retrieved June 10, 2019.

- ^ "Taylor Swift No. 1 on iTunes". Great American Country. December 19, 2007. Archived from the original on March 3, 2012. Retrieved July 5, 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Taylor Swift – Chart history". Billboard. Archived from the original on August 9, 2016. Retrieved July 26, 2016.

- ^ "Taylor Swift owns top of country chart". Country Standard Time. July 23, 2008. Archived from the original on July 31, 2008. Retrieved December 26, 2008.

- ^ "Wal-Mart "Eyes" New Taylor Swift Project". Great American Country. Archived from the original on July 23, 2008. Retrieved July 24, 2008.

- ^ "Taylor Swift Joins George Strait's 2007 Tour". CMT. November 17, 2006. Retrieved February 16, 2020.

- ^ "Brad Paisley Plans Tour With Three Opening Acts". CMT. January 9, 2007. Retrieved February 16, 2020.

- ^ "Taylor Swift Joins Tim McGraw, Faith Hill on Tour". CMT. June 1, 2007. Retrieved February 16, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Taylor Swift Youngest Winner of Songwriter/Artist Award". Great American Country. October 16, 2007. Archived from the original on January 11, 2015. Retrieved February 2, 2015.

- ^ "Photos : All Taylor Swift Pictures : Horizon Award Winner Poses in the Pressroom". CMT. September 7, 2007. Archived from the original on November 13, 2012. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ "Photos : 43rd Annual ACM Awards – Onstage: Winners : Acceptance Speech". CMT. May 18, 2008. Archived from the original on November 13, 2012. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ "Taylor Swift, Rascal Flatts, Carrie Underwood Score at 2008 AMA Awards" (Blog). Roughstock.com. November 24, 2008. Archived from the original on July 10, 2014. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ "Amy Winehouse Wins Best New Artist, Kanye West Pays Tribute to Mom – Grammy Awards 2008, Grammy Awards". People. October 2, 2008. Archived from the original on November 13, 2012. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ "Rascal Flatts Announce Summer Tour With Taylor Swift". CMT. May 5, 2008. Retrieved June 5, 2019.

- ^ Caplan, David (September 8, 2008). "Scoop". People. Archived from the original on February 2, 2016. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

- ^ Rizzo, Monica (November 24, 2008). "Scoop – Couples, Camilla Belle, Joe Jonas". People. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

- ^ Akers, Shelley (June 9, 2008). "Taylor Swift to Appear in Hannah Montana Movie". People. Archived from the original on October 27, 2017. Retrieved October 27, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Hannah Montana: The Movie (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack) by Hannah Montana". iTunes Store. January 2009. Archived from the original on May 2, 2016. Retrieved August 2, 2016.

- ^ "Taylor Swift – Fearless" (in Portuguese). Universal Music Group. Archived from the original on January 18, 2021. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ^ Raphael, Amy (February 1, 2009). "First, she conquered Nashville. Now she's set for world domination". The Observer. ProQuest 250507223. Retrieved December 9, 2022.

- ^ Widdicombe, Lizzie (October 10, 2011). "You Belong with Me". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on July 24, 2014. Retrieved July 24, 2014.

- ^ "Discography Taylor Swift". ARIA Charts. Archived from the original on March 21, 2012. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ Trust, Gary (December 15, 2009). "Best of 2009: Part 1". Billboard. Archived from the original on March 3, 2013. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ^ Ben-Yehuda, Ayala (August 13, 2009). "Black Eyed Peas, Jason Mraz Tie Records on Billboard Hot 100". Billboard. Archived from the original on May 8, 2013. Retrieved March 13, 2010.

- ^ Trust, Gary (September 24, 2009). "Taylor Swift Climbs Hot 100, Black Eyed Peas Still No. 1". Billboard. Archived from the original on February 1, 2013. Retrieved September 20, 2022.