Censorship

Censorship is the suppression of speech or other public communication which may be considered objectionable, harmful, sensitive, politically incorrect or inconvenient as determined by a government, media outlet or other controlling body. It can be done by governments and private organizations or by individuals who engage in self-censorship. It occurs in a variety of different contexts including speech, books, music, films, and other arts, the press, radio, television, and the Internet for a variety of reasons including national security, to control obscenity, child pornography, and hate speech, to protect children, to promote or restrict political or religious views, and to prevent slander and libel. It may or may not be legal. Many countries provide strong protections against censorship by law, but none of these protections are absolute and it is frequently necessary to balance conflicting rights in order to determine what can and cannot be censored.

History

[edit]

Socrates defied censorship and was sentenced to drink poison in 399 BC for promoting his philosophies. Plato is said to have advocated censorship in his essay on The Republic. The playwright Euripides (480–406 BC) defended the true liberty of freeborn men, the right to speak freely.[2]

Rationale

[edit]The rationale for censorship is different for various types of information censored:

- Moral censorship is the removal of materials that are obscene or otherwise considered morally questionable. Pornography, for example, is often censored under this rationale, especially child pornography, which is illegal and censored in most jurisdictions in the world.[3][4]

- Military censorship is the process of keeping military intelligence and tactics confidential and away from the enemy. This is used to counter espionage, which is the process of gleaning military information.

- Political censorship occurs when governments hold back information from their citizens. This is often done to exert control over the populace and prevent free expression that might foment rebellion.

- Religious censorship is the means by which any material considered objectionable by a certain faith is removed. This often involves a dominant religion forcing limitations on less prevalent ones. Alternatively, one religion may shun the works of another when they believe the content is not appropriate for their faith.

- Corporate censorship is the process by which editors in corporate media outlets intervene to disrupt the publishing of information that portrays their business or business partners in a negative light,[5][6] or intervene to prevent alternate offers from reaching public exposure.[7]

Types

[edit]Political

[edit]Strict censorship existed in the Eastern Bloc.[9] Throughout the bloc, the various ministries of culture held a tight rein on their writers.[10] Cultural products there reflected the propaganda needs of the state.[10] Party-approved censors exercised strict control in the early years.[11] In the Stalinist period, even the weather forecasts were changed if they had the temerity to suggest that the sun might not shine on May Day.[11] Under Nicolae Ceauşescu in Romania, weather reports were doctored so that the temperatures were not seen to rise above or fall below the levels which dictated that work must stop.[11]

Independent journalism did not exist in the Soviet Union until Mikhail Gorbachev became its leader; all reporting was directed by the Communist Party or related organizations. Pravda, the predominant newspaper in the Soviet Union, had a monopoly. Foreign newspapers were available only if they were published by Communist Parties sympathetic to the Soviet Union.

Possession and use of copying machines was tightly controlled in order to hinder production and distribution of samizdat, illegal self-published books and magazines. Possession of even a single samizdat manuscript such as a book by Andrei Sinyavsky was a serious crime which might involve a visit from the KGB. Another outlet for works which did not find favor with the authorities was publishing abroad.

The People's Republic of China employs sophisticated censorship mechanisms, referred to as the Golden Shield Project, to monitor the internet. Popular search engines such as Baidu also remove politically sensitive search results.[12]

Iraq under Baathist Saddam Hussein had much the same techniques of press censorship as did Romania under Nicolae Ceauşescu but with greater potential violence.[citation needed]

Cuban media is operated under the supervision of the Communist Party's Department of Revolutionary Orientation, which "develops and coordinates propaganda strategies".[13] Connection to the Internet is restricted and censored.[14]

Censorship also takes place in capitalist nations, such as Uruguay. In 1973, a military coup took power in Uruguay, and the State practiced censorship. For example, writer Eduardo Galeano was imprisoned and later was forced to flee. His book Open Veins of Latin America was banned by the right-wing military government, not only in Uruguay, but also in Chile and Argentina.[15]

Critics of the Campaign finance reform in the United States claim that this reform imposes widespread restrictions on political speech.[16][17]

State secrets and prevention of attention

[edit]

In wartime, explicit censorship is carried out with the intent of preventing the release of information that might be useful to an enemy. Typically it involves keeping times or locations secret, or delaying the release of information (e.g., an operational objective) until it is of no possible use to enemy forces. The moral issues here are often seen as somewhat different, as the proponents of this form of censorship argues that release of tactical information usually presents a greater risk of casualties among one's own forces and could possibly lead to loss of the overall conflict.

During World War I letters written by British soldiers would have to go through censorship. This consisted of officers going through letters with a black marker and crossing out anything which might compromise operational secrecy before the letter was sent. The World War II catchphrase "Loose lips sink ships" was used as a common justification to exercise official wartime censorship and encourage individual restraint when sharing potentially sensitive information.

An example of "sanitization" policies comes from the USSR under Joseph Stalin, where publicly used photographs were often altered to remove people whom Stalin had condemned to execution. Though past photographs may have been remembered or kept, this deliberate and systematic alteration to all of history in the public mind is seen as one of the central themes of Stalinism and totalitarianism.

Censorship is occasionally carried out to aid authorities or to protect an individual, as with some kidnappings when attention and media coverage of the victim can sometimes be seen as unhelpful.[18][19]

Religion

[edit]Censorship by religion is a form of censorship where freedom of expression is controlled or limited using religious authority or on the basis of the teachings of the religion. This form of censorship has a long history and is practiced in many societies and by many religions. Examples include the Galileo affair, Edict of Compiègne, the Index Librorum Prohibitorum (list of prohibited books) and the condemnation of Salman Rushdie's novel The Satanic Verses by Iranian leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. Images of the Islamic figure Muhammad are also regularly censored.

Educational sources

[edit]

The content of school textbooks is often the issue of debate, since their target audience is young people, and the term "whitewashing" is the one commonly used to refer to removal of critical or conflicting events. The reporting of military atrocities in history is extremely controversial, as in the case of The Holocaust (or Holocaust denial), Bombing of Dresden, the Nanking Massacre as found with Japanese history textbook controversies, the Armenian Genocide, the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989, and the Winter Soldier Investigation of the Vietnam War.

In the context of secondary school education, the way facts and history are presented greatly influences the interpretation of contemporary thought, opinion and socialization. One argument for censoring the type of information disseminated is based on the inappropriate quality of such material for the young. The use of the "inappropriate" distinction is in itself controversial, as it changed heavily. A Ballantine Books version of the book Fahrenheit 451 which is the version used by most school classes[20] contained approximately 75 separate edits, omissions, and changes from the original Bradbury manuscript.

In February 2006 a National Geographic cover was censored by the Nashravaran Journalistic Institute. The offending cover was about the subject of love and a picture of an embracing couple was hidden beneath a white sticker.[21][21]

Copy, picture, and writer approval

[edit]Copy approval is the right to read and amend an article, usually an interview, before publication. Many publications refuse to give copy approval but it is increasingly becoming common practice when dealing with publicity anxious celebrities.[22] Picture approval is the right given to an individual to choose which photos will be published and which will not. Robert Redford is well known for insisting upon picture approval.[23] Writer approval is when writers are chosen based on whether they will write flattering articles or not. Hollywood publicist Pat Kingsley is known for banning certain writers who wrote undesirably about one of her clients from interviewing any of her other clients.[citation needed]

Creative censorship

[edit]There are many ways that censors exhibit creativity, but a specific variant is of concern in which censors rewrite texts, giving these texts secret co-authors. This form of censorship is discussed in George Orwell's novel Nineteen Eighty-Four.[citation needed][original research?]

Self-censorship

[edit]

According to a Pew Research Center and the Columbia Journalism Review survey, "About one-quarter of the local and national journalists say they have purposely avoided newsworthy stories, while nearly as many acknowledge they have softened the tone of stories to benefit the interests of their news organizations. Fully four-in-ten (41%) admit they have engaged in either or both of these practices."[25]

Censorship by medium

[edit]Books

[edit]

Book censorship can be enacted at the national or sub-national level, and can carry legal penalties for their infraction. Books may also be challenged at a local, community level. As a result, books can be removed from schools or libraries, although these bans do not extend outside of that area.

Films

[edit]Aside from the usual justifications of pornography and obscenity, some films are censored due to changing racial attitudes or political correctness in order to avoid ethnic stereotyping and/or ethnic offense despite its historical or artistic value. One example is the still withdrawn "Censored Eleven" series of animated cartoons, which may have been innocent then, but are "incorrect" now.

Film censorship is carried out by various countries to differing degrees. For example, only 34 foreign films a year are approved for official distribution in China's strictly controlled film market.[26]

Music

[edit]Music censorship has been implemented by states, religions, educational systems, families, retailers and lobbying groups – and in most cases they violate international conventions of human rights.[27]

Maps

[edit]Censorship of maps is often employed for military purposes. For example, the technique was used in former East Germany, especially for the areas near the border to West Germany in order to make attempts of defection more difficult. Censorship of maps is also applied by Google maps, where certain areas are grayed out or blacked or areas are purposely left outdated with old imagery.[28]

Internet

[edit]

Internet censorship is control or suppression of the publishing or accessing of information on the Internet. It may be carried out by governments or by private organizations either at the behest of government or on their own initiative. Individuals and organizations may engage in self-censorship on their own or due to intimidation and fear.

The issues associated with Internet censorship are similar to those for offline censorship of more traditional media. One difference is that national borders are more permeable online: residents of a country that bans certain information can find it on websites hosted outside the country. Thus censors must work to prevent access to information even though they lack physical or legal control over the websites themselves. This in turn requires the use of technical censorship methods that are unique to the Internet, such as site blocking and content filtering.[32]

Unless the censor has total control over all Internet-connected computers, such as in North Korea or Cuba, total censorship of information is very difficult or impossible to achieve due to the underlying distributed technology of the Internet. Pseudonymity and data havens (such as Freenet) protect free speech using technologies that guarantee material cannot be removed and prevents the identification of authors. Technologically savvy users can often find ways to access blocked content. Nevertheless, blocking remains an effective means of limiting access to sensitive information for most users when censors, such as those in China, are able to devote significant resources to building and maintaining a comprehensive censorship system.[32]

Views about the feasibility and effectiveness of Internet censorship have evolved in parallel with the development of the Internet and censorship technologies:

- A 1993 Time Magazine article quotes computer scientist John Gillmore, one of the founders of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, as saying "The Net interprets censorship as damage and routes around it."[33]

- In November 2007, "Father of the Internet" Vint Cerf stated that he sees government control of the Internet failing because the Web is almost entirely privately owned.[34]

- A report of research conducted in 2007 and published in 2009 by the Beckman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University stated that: "We are confident that the [censorship circumvention] tool developers will for the most part keep ahead of the governments' blocking efforts", but also that "...we believe that less than two percent of all filtered Internet users use circumvention tools".[35]

- In contrast, a 2011 report by researchers at the Oxford Internet Institute published by UNESCO concludes "... the control of information on the Internet and Web is certainly feasible, and technological advances do not therefore guarantee greater freedom of speech."[32]

A BBC World Service poll of 27,973 adults in 26 countries, including 14,306 Internet users,[36] was conducted between 30 November 2009 and 7 February 2010. The head of the polling organization felt, overall, that the poll showed that:

- Despite worries about privacy and fraud, people around the world see access to the internet as their fundamental right. They think the web is a force for good, and most don’t want governments to regulate it.[37]

The poll found that nearly four in five (78%) Internet users felt that the Internet had brought them greater freedom, that most Internet users (53%) felt that "the internet should never be regulated by any level of government anywhere", and almost four in five Internet users and non-users around the world felt that access to the Internet was a fundamental right (50% strongly agreed, 29% somewhat agreed, 9% somewhat disagreed, 6% strongly disagreed, and 6% gave no opinion).[38]

Surveillance as an aid to censorship

[edit]Surveillance and censorship are different. Surveillance can be performed without censorship, but it is harder to engage in censorship without some form of surveillance.[39] And even when surveillance does not lead directly to censorship, the widespread knowledge or belief that a person, their computer, or their use of the Internet is under surveillance can lead to self-censorship.[40]

Protection of sources is no longer just a matter of journalistic ethics; it increasingly also depends on the journalist’s computer skills and all journalists should equip themselves with a “digital survival kit” if they are exchanging sensitive information online or storing it on a computer or mobile phone.[41][42] And individuals associated with high profile rights organizations, dissident, protest, or reform groups are urged to take extra precautions to protect their online identities.[43]

Implementation

[edit]

The former Soviet Union maintained a particularly extensive program of state-imposed censorship. The main organ for official censorship in the Soviet Union was the Chief Agency for Protection of Military and State Secrets generally known as the Glavlit, its Russian acronym. The Glavlit handled censorship matters arising from domestic writings of just about any kind—even beer and vodka labels. Glavlit censorship personnel were present in every large Soviet publishing house or newspaper; the agency employed some 70,000 censors to review information before it was disseminated by publishing houses, editorial offices, and broadcasting studios. No mass medium escaped Glavlit's control. All press agencies and radio and television stations had Glavlit representatives on their editorial staffs.[citation needed]

Sometimes, public knowledge of the existence of a specific document is subtly suppressed, a situation resembling censorship. The authorities taking such action will justify it by declaring the work to be "subversive" or "inconvenient". An example is Michel Foucault's 1978 text "Sexual Morality and the Law" (later republished as "The Danger of Child Sexuality"), originally published as La loi de la pudeur [literally, "the law of decency"]. This work defends the decriminalization of statutory rape and the abolition of age of consent laws.[citation needed]

When a publisher comes under pressure to suppress a book, but has already entered into a contract with the author, they will sometimes effectively censor the book by deliberately ordering a small print run and making minimal, if any, attempts to publicize it. This practice became known in the early 2000s as privishing (private publishing).[44]

Criticism of censorship

[edit]Censorship has been criticized throughout history for being unfair and hindering progress. In a 1997 essay on Internet censorship, social commentator Michael Landier claims that censorship is counter productive as it prevents the censored topic from being discussed. Landier expands his argument by claiming that those who impose censorship must consider what they censor to be true, as individuals believing themselves to be correct would welcome the opportunity to disprove those with opposing views.[45]

Censorship is often used to impose moral values on society, as in the censorship of material considered obscene. English novelist E. M. Forster was a staunch opponent of censoring material on the grounds that it was obscene or immoral, raising the issue of moral subjectivity and the constant changing of moral values. In regard to the novel "Lady Chatterley's Lover" Forster wrote:[46]

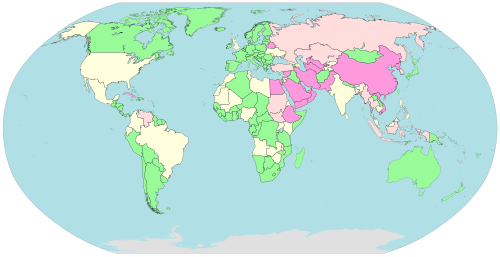

Censorship by country

[edit]Censorship by country collects information on censorship, Internet censorship, Freedom of the Press, Freedom of speech, and Human Rights by country and presents it in a sortable table, together with links to articles with more information. In addition to countries, the table includes information on former countries, disputed countries, political sub-units within countries, and regional organizations.

See also

[edit]|

Related articles

|

Freedoms

|

References

[edit]- ^ Sui-Lee Wee; Ben Blanchard (June 4, 2012). "China blocks Tiananmen talk on crackdown anniversary". Reuters. Retrieved May 8, 2013.

- ^ "The Long History of Censorship", Mette Newth, Beacon for Freedom of Expression (Norway), 2010

- ^ "Child Pornography: Model Legislation & Global Review" (PDF) (5 ed.). International Centre for Missing & Exploited Children. 2008. Retrieved 2012-08-25.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ "World Congress against CSEC". Csecworldcongress.org. 2002-07-27. Retrieved 2011-10-21.

- ^ Timothy Jay (2000). Why We Curse: A Neuro-psycho-social Theory of Speech. John Benjamins Publishing Company. pp. 208–209. ISBN 1-55619-758-6.

- ^ David Goldberg, Stefaan G. Verhulst, Tony Prosser (1998). Regulating the Changing Media: A Comparative Study. Oxford University Press. p. 207. ISBN 0-19-826781-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ McCullagh, Declan (2003-06-30). "Microsoft's new push in Washington". CNET. Retrieved 2011-10-21.

- ^ The Commissar vanishes (The Newseum)

- ^ Template:Harvnb

- ^ Jump up to: a b Template:Harvnb

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Template:Harvnb

- ^ Baidu’s Internal Monitoring and Censorship Document Leaked (1), Xiao Qiang, China Digital Times, April 30, 2009

Baidu’s Internal Monitoring and Censorship Document Leaked (2)

Baidu’s Internal Monitoring and Censorship Document Leaked (3) - ^ "10 most censored countries". The Committee to Protect Journalists.

- ^ "Going online in Cuba: Internet under surveillance" (PDF). Reporters Without Borders. 2006.

- ^ "Fresh Off Worldwide Attention for Joining Obama's Book Collection, Uruguayan Author Eduardo Galeano Returns with "Mirrors: Stories of Almost Everyone"". Democracynow.org. 28 May 2009. Retrieved 2011-10-21.

- ^ "The Trick of Campaign Finance Reform". Christian Science Monitor.

- ^ "Felonious Advocacy". reason.

- ^ New York Times

- ^ The Raw Story | Investigative News and Politics

- ^ Bradbury, Ray. Fahrenheit 451. Del Rey Books. April 1991.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lundqvist, J. "More pictures of Iranian Censorship". Retrieved August 2007-01-21.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Ian Mayes (2005-04-23). "The readers' editor on requests that are always refused". London: The Guardian. Retrieved August 2007-01-21.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Barber, Lynn (2002-01-27). "Caution: big name ahead". London: The Observer. Retrieved August 2007-01-21.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Green Illusions: The Dirty Secrets of Clean Energy and the Future of Environmentalism, Ozzie Zehner, University of Nebraska Press, 2012, 464 pp, ISBN 978-0-8032-3775-9. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- ^ "Self Censorship: How Often and Why". Pew Research Center.

- ^ "Why China is letting 'Django Unchained' slip through its censorship regime". Quartz. March 13, 2013.

- ^ "What is Music Censorship?". Freemuse.org. 1 January 2001. Retrieved 2008-10-25.

- ^ Jenna Johnson (2007-07-22). "Google's View of D.C. Melds New and Sharp, Old and Fuzzy". News. Washington Post. Retrieved 2007-07-22.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ OpenNet Initiative "Summarized global Internet filtering data spreadsheet", 8 November 2011 and "Country Profiles", the OpenNet Initiative is a collaborative partnership of the Citizen Lab at the Munk School of Global Affairs, University of Toronto; the Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University; and the SecDev Group, Ottawa

- ^ Internet Enemies, Reporters Without Borders (Paris), 12 March 2012

- ^ Due to legal concerns the OpenNet Initiative does not check for filtering of child pornography and because their classifications focus on technical filtering, they do not include other types of censorship.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Freedom of Connection, Freedom of Expression: The Changing Legal and Regulatory Ecology Shaping the Internet, Dutton, William H.; Dopatka, Anna; Law, Ginette; Nash, Victoria, Division for Freedom of Expression, Democracy and Peace, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), Paris, 2011, 103 pp., ISBN 978-92-3-104188-4

- ^ "First Nation in Cyberspace", Philip Elmer-Dewitt, Time, 6 December 1993, No. 49

- ^ "Cerf sees government control of Internet failing", Pedro Fonseca, Reuters, 14 November 2007

- ^ 2007 Circumvention Landscape Report: Methods, Uses, and Tools, Hal Roberts, Ethan Zuckerman, and John Palfrey, Beckman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University, March 2009

- ^ For the BBC poll Internet users are those who used the Internet within the previous six months.

- ^ "BBC Internet Poll: Detailed Findings", BBC World Service, 8 March 2010

- ^ "Internet access is 'a fundamental right'", BBC News, 8 March 2010

- ^ "Censorship is inseparable from surveillance", Cory Doctorow, The Guardian, 2 March 2012

- ^ "Online Censorship : Ubiquitous Big Brother, witchhunt for dissidents", WeFightCensorship.org, Reporters Without Borders, retrieved 12 March 2013

- ^ "When Secrets Aren’t Safe With Journalists", Christopher Soghoian, New York Times, 26 October 2011

- ^ The Enemies of the Internet Special Edition : Surveillance, Reporters Without Borders, 12 March 2013

- ^ Everyone's Guide to By-passing Internet Censorship, The Citizen Lab, University of Toronto, September 2007

- ^ Winkler, David (11 July 2002). "Journalists Thrown 'Into the Buzzsaw'". CommonDreams.org.

- ^ "Internet Censorship is Absurd and Unconstitutional", Michael Landier, 4 June 1997

- ^ "The Trial of Lady Chatterley's Lover", Paul Gallagher, Dangerous Minds, 10 November 2010

Further reading

[edit]- Abbott, Randy. "A Critical Analysis of the Library-Related Literature Concerning Censorship in Public Libraries and Public School Libraries in the United States During the 1980s." Project for degree of Education Specialist, University of South Florida, December 1987.

- Burress, Lee. Battle of the Books. Metuchen, NJ: The Scarecrow Press, 1989.

- Butler, Judith, "Excitable Speech: A Politics of the Performative"(1997)

- Foucault, Michel, edited by Lawrence D. Kritzman. Philosophy, Culture: interviews and other writings 1977–1984 (New York/London: 1988, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-90082-4) (The text Sexual Morality and the Law is Chapter 16 of the book).

- Gilbert, Nora. "Better Left Unsaid: Victorian Novels, Hays Code Films, and the Benefits of Censorship." Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2013.

- O'Reilly, Robert C. & Parker, Larry. "Censorship or Curriculum Modification?" Paper presented at a School Boards Association, 1982, 14 p.

- Hendrikson, Leslie. "Library Censorship: ERIC Digest No. 23." ERIC Clearinghouse for Social Studies/Social Science Education, Boulder, Colorado, November 1985.

- Wittern-Keller, Laura. Freedom of the Screen: Legal Challenges to State Film Censorship, 1915–1981. University Press of Kentucky 2008

- Hoffman, Frank. "Intellectual Freedom and Censorship." Metuchen, NJ: The Scarecrow Press, 1989.

- Marek, Kate. "Schoolbook Censorship USA." June 1987.

- Mathiesen, Kay Censorship and Access to Information HANDBOOK OF INFORMATION AND COMPUTER ETHICS, Kenneth E. Himma, Herman T. Tavani, eds., John Wiley and Sons, New York, 2008

- National Coalition against Censorship (NCAC). "Books on Trial: A Survey of Recent Cases." January 1985.

- Ringmar, Erik A Blogger's Manifesto: Free Speech and Censorship in the Age of the Internet (London: Anthem Press, 2007)

- Small, Robert C., Jr. "Preparing the New English Teacher to Deal with Censorship, or Will I Have to Face it Alone?" Annual Meeting of the National Council of Teachers of English, 1987, 16 p.

- (Arguing that an English teacher should get advice from school librarians in preparing to encounter three levels of censorship:

- Rejection of adolescent fiction and popular teen magazines as having low value,

- Experienced colleagues discouraging "difficult" lesson plans,

- Outside interest groups limiting students' exposure.

- Supreme Court rejects advocates' plea to preserve useful formats

- Terry, John David II. "Censorship: Post Pico." In "School Law Update, 1986," edited by Thomas N. Jones and Darel P. Semler.

- World Book Encyclopedia, volume 3 (C-Ch), pages 345, 346

Template:Censorship Template:Media manipulation Template:Propaganda Template:Internet censorship by country

- Pages using the JsonConfig extension

- CS1 errors: missing periodical

- CS1 errors: invalid parameter value

- CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list

- CS1 errors: dates

- CS1 maint: date and year

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Wikipedia pages with incorrect protection templates

- Articles with missing files

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from April 2010

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Articles with unsourced statements from August 2008

- Articles with unsourced statements from April 2011

- All articles that may contain original research

- Articles that may contain original research from April 2011

- Articles with unsourced statements from March 2013

- Censorship

- Historical deletion

- Propaganda techniques

- Ethically disputed political practices