World War II

""Goak here": A.J.P. Taylor and 'The Origins of the Second World War.'". Canadian Journal of History. 1 August 1996.

Start and end dates

[edit]It is generally considered that, in Europe, World War II started on 1 September 1939, beginning with the German invasion of Poland and the United Kingdom and France's declaration of war on Germany two days later on 3 September 1939. Dates for the beginning of the Pacific War include the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War on 7 July 1937,[1][2] or the earlier Japanese invasion of Manchuria, on 19 September 1931.[3][4] Others follow the British historian A. J. P. Taylor, who held that the Sino-Japanese War and war in Europe and its colonies occurred simultaneously, and the two wars became World War II in 1941.[5] Other starting dates sometimes used for World War II include the Italian invasion of Abyssinia on .[6] The British historian Antony Beevor views the beginning of World War II as the Battles of Khalkhin Gol fought between Japan and the forces of Mongolia and the Soviet Union from May to September 1939.[7] Others view the Spanish Civil War as the start or prelude to World War II.[8][9]

Aftermath

[edit]The Allies established occupation administrations in Austria and Germany, both initially divided between western and eastern occupation zones controlled by the Western Allies and the Soviet Union, respectively. However, their paths soon diverged. In Germany, the western and eastern occupation zones controlled by the Western Allies and the Soviet Union officially ended in 1949, with the respective zones becoming separate countries, West Germany and East Germany. In Austria, however, occupation continued until 1955, when a joint settlement between the Western Allies and the Soviet Union permitted the reunification of Austria as a neutral democratic state, officially non-aligned with any political bloc (although in practice having better relations with the Western Allies). A denazification program in Germany led to the prosecution of Nazi war criminals in the Nuremberg trials and the removal of ex-Nazis from power, although this policy moved towards amnesty and re-integration of ex-Nazis into West German society.

Germany lost a quarter of its pre-war (1937) territory. Among the eastern territories, Silesia, Neumark and most of Pomerania were taken over by Poland, and East Prussia was divided between Poland and the Soviet Union, followed by the expulsion to Germany of the nine million Germans from these provinces, as well as three million Germans from the Sudetenland in Czechoslovakia. By the 1950s, one-fifth of West Germans were refugees from the east. The Soviet Union also took over the Polish provinces east of the Curzon line, from which 2 million Poles were expelled; north-east Romania, parts of eastern Finland, and the three Baltic states were annexed into the Soviet Union.

In an effort to maintain world peace, the Allies formed the United Nations, which officially came into existence on 24 October 1945, and adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948 as a common standard for all member nations. The great powers that were the victors of the war—France, China, the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union and the United States—became the permanent members of the UN's Security Council. The five permanent members remain so to the present, although there have been two seat changes, between the Republic of China and the People's Republic of China in 1971, and between the Soviet Union and its successor state, the Russian Federation, following the dissolution of the USSR in 1991. The alliance between the Western Allies and the Soviet Union had begun to deteriorate even before the war was over.

Besides Germany, the rest of Europe was also divided into Western and Soviet spheres of influence. Most eastern and central European countries fell into the Soviet sphere, which led to establishment of Communist-led regimes, with full or partial support of the Soviet occupation authorities. As a result, East Germany, Poland, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, and Albania became Soviet satellite states. Communist Yugoslavia conducted a fully independent policy, causing tension with the Soviet Union. A Communist uprising in Greece was put down with Anglo-American support and the country remained aligned with the West.

Post-war division of the world was formalised by two international military alliances, the United States-led NATO and the Soviet-led Warsaw Pact. The long period of political tensions and military competition between them, the Cold War, would be accompanied by an unprecedented arms race and number of proxy wars throughout the world.

In Asia, the United States led the occupation of Japan and administered Japan's former islands in the Western Pacific, while the Soviets annexed South Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands. Korea, formerly under Japanese colonial rule, was divided and occupied by the Soviet Union in the North and the United States in the South between 1945 and 1948. Separate republics emerged on both sides of the 38th parallel in 1948, each claiming to be the legitimate government for all of Korea, which led ultimately to the Korean War.

transferred most of Germany's industrial plants and exacted from its satellite states.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; refs with no name must have content; see the help page ().

[10] much later.[11] China returned to its pre-war industrial production by 1952.[12]

Impact

[edit]Casualties and war crimes

[edit]The Soviet Union alone lost around 27 million people during the war, including 8.7 million military and 19 million civilian deaths. A quarter of the total people in the Soviet Union were wounded or killed. Germany sustained 5.3 million military losses, mostly on the Eastern Front and during the final battles in Germany.

An estimated 11[13] to 17 million[14] civilians died as a direct or as an indirect result of Hitler's racist policies, including mass killing of around 6 million Jews, along with Roma, homosexuals, at least 1.9 million ethnic Poles[15][16] and millions of other Slavs (including Russians, Ukrainians and Belarusians), and other ethnic and minority groups.[17][14] Between 1941 and 1945, more than 200,000 ethnic Serbs, along with gypsies and Jews, were persecuted and murdered by the Axis-aligned Croatian Ustaše in Yugoslavia.[18] Concurrently, Muslims and Croats were persecuted and killed by Serb nationalist Chetniks,[19] with an estimated 50,000–68,000 victims (of which 41,000 were civilians).[20] Also, more than 100,000 Poles were massacred by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army in the Volhynia massacres, between 1943 and 1945.[21] At the same time, about 10,000–15,000 Ukrainians were killed by the Polish Home Army and other Polish units, in reprisal attacks.[22]

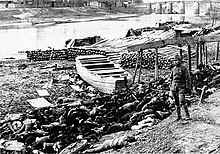

In Asia and the Pacific, the number of people killed by Japanese troops remains contested. According to R.J. Rummel, the Japanese killed between 3 million and more than 10 million people, with the most probable case of almost 6,000,000 people.[23] According to the British historian M. R. D. Foot, civilian deaths are between 10 million and 20 million, whereas Chinese military casualties (killed and wounded) are estimated to be over five million.[24] Other estimates say that up to 30 million people, most of them civilians, were killed.[25][26] The most infamous Japanese atrocity was the Nanking Massacre, in which fifty to three hundred thousand Chinese civilians were raped and murdered.[27] Mitsuyoshi Himeta reported that 2.7 million casualties occurred during the Sankō Sakusen. General Yasuji Okamura implemented the policy in Heipei and Shantung.[28]

Axis forces employed biological and chemical weapons. The Imperial Japanese Army used a variety of such weapons during its invasion and occupation of China (see Unit 731)[29][30] and in early conflicts against the Soviets.[31] Both the Germans and the Japanese tested such weapons against civilians,[32] and sometimes on prisoners of war.[33]

The Soviet Union was responsible for the Katyn massacre of 22,000 Polish officers,[34] and the imprisonment or execution of hundreds of thousands of political prisoners by the NKVD secret police, along with mass civilian deportations to Siberia, in the Baltic states and eastern Poland annexed by the Red Army.[35] Soviet soldiers committed mass rapes in occupied territories, especially in Germany.[36][37] The exact number of German women and girls raped by Soviet troops during the war and occupation is uncertain, but historians estimate their numbers are likely in the hundreds of thousands, and possibly as many as two million,[38] while figures for women raped by German soldiers in the Soviet Union go as far as ten million.[39][40]

The mass bombing of cities in Europe and Asia has often been called a war crime, although no positive or specific customary international humanitarian law with respect to aerial warfare existed before or during World War II.[41] The USAAF bombed a total of 67 Japanese cities, killing 393,000 civilians, including from the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and destroying 65% of built-up areas.[42]

Genocide, concentration camps, and slave labour

[edit]

Nazi Germany, under the dictatorship of Adolf Hitler, was responsible for the Holocaust (which killed approximately 6 million Jews) as well as for killing 2.7 million ethnic Poles[43] and 4 million others who were deemed "unworthy of life" (including the disabled and mentally ill, Soviet prisoners of war, Romani, homosexuals, Freemasons, and Jehovah's Witnesses) as part of a program of deliberate extermination, in effect becoming a "genocidal state".[44] Soviet POWs were kept in especially unbearable conditions, and 3.6 million Soviet POWs out of 5.7 million died in Nazi camps during the war.[45][46] In addition to concentration camps, death camps were created in Nazi Germany to exterminate people on an industrial scale. Nazi Germany extensively used forced labourers; about 12 million Europeans from German-occupied countries were abducted and used as a slave work force in German industry, agriculture and war economy.[47]

The Soviet Gulag became a de facto system of deadly camps during 1942–43, when wartime privation and hunger caused numerous deaths of inmates,[48] including foreign citizens of Poland and other countries occupied in 1939–40 by the Soviet Union, as well as Axis POWs.[49] By the end of the war, most Soviet POWs liberated from Nazi camps and many repatriated civilians were detained in special filtration camps where they were subjected to NKVD evaluation, and 226,127 were sent to the Gulag as real or perceived Nazi collaborators.[50]

Japanese prisoner-of-war camps, many of which were used as labour camps, also had high death rates. The International Military Tribunal for the Far East found the death rate of Western prisoners was 27 per cent (for American POWs, 37 per cent),[51] seven times that of POWs under the Germans and Italians.[52] While 37,583 prisoners from the UK, 28,500 from the Netherlands, and 14,473 from the United States were released after the surrender of Japan, the number of Chinese released was only 56.[53]

At least five million Chinese civilians from northern China and Manchukuo were enslaved between 1935 and 1941 by the East Asia Development Board, or Kōain, for work in mines and war industries. After 1942, the number reached 10 million.[54] In Java, between 4 and 10 million rōmusha (Japanese: "manual labourers"), were forced to work by the Japanese military. About 270,000 of these Javanese labourers were sent to other Japanese-held areas in Southeast Asia, and only 52,000 were repatriated to Java.[55]

Occupation

[edit]

In Europe, occupation came under two forms. In Western, Northern, and Central Europe (France, Norway, Denmark, the Low Countries, and the annexed portions of Czechoslovakia) Germany established economic policies through which it collected roughly 69.5 billion reichsmarks (27.8 billion U.S. dollars) by the end of the war; this figure does not include the sizeable plunder of industrial products, military equipment, raw materials and other goods.[56] Thus, the income from occupied nations was over 40 percent of the income Germany collected from taxation, a figure which increased to nearly 40 percent of total German income as the war went on.[57]

In the East, the intended gains of Lebensraum were never attained as fluctuating front-lines and Soviet scorched earth policies denied resources to the German invaders.[58] Unlike in the West, the Nazi racial policy encouraged extreme brutality against what it considered to be the "inferior people" of Slavic descent; most German advances were thus followed by mass executions.[59] Although resistance groups formed in most occupied territories, they did not significantly hamper German operations in either the East[60] or the West[61] until late 1943.

In Asia, Japan termed nations under its occupation as being part of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, essentially a Japanese hegemony which it claimed was for purposes of liberating colonised peoples.[62] Although Japanese forces were sometimes welcomed as liberators from European domination, Japanese war crimes frequently turned local public opinion against them.[63] During Japan's initial conquest, it captured 4,000,000 barrels (640,000 m3) of oil (~550,000 tonnes) left behind by retreating Allied forces; and by 1943, was able to get production in the Dutch East Indies up to 50 million barrels (7,900,000 m3) of oil (~6.8 million tonnes), 76 per cent of its 1940 output rate.[63]

Home fronts and production

[edit]In Europe, before the outbreak of the war, the Allies had significant advantages in both population and economics. In 1938, the Western Allies (United Kingdom, France, Poland and the British Dominions) had a 30 percent larger population and a 30 percent higher gross domestic product than the European Axis powers (Germany and Italy); if colonies are included, the Allies had more than a 5:1 advantage in population and a nearly 2:1 advantage in GDP.[64] In Asia at the same time, China had roughly six times the population of Japan but only an 89 percent higher GDP; this is reduced to three times the population and only a 38 percent higher GDP if Japanese colonies are included.[64]

The United States produced about two-thirds of all the munitions used by the Allies in World War II, including warships, transports, warplanes, artillery, tanks, trucks, and ammunition.[65] Though the Allies' economic and population advantages were largely mitigated during the initial rapid blitzkrieg attacks of Germany and Japan, they became the decisive factor by 1942, after the United States and Soviet Union joined the Allies, as the war largely settled into one of attrition.[66] While the Allies' ability to out-produce the Axis is often attributed[by whom?] to the Allies having more access to natural resources, other factors, such as Germany and Japan's reluctance to employ women in the labour force,[67] Allied strategic bombing,[68] and Germany's late shift to a war economy[69] contributed significantly. Additionally, neither Germany nor Japan planned to fight a protracted war, and had not equipped themselves to do so.[70] To improve their production, Germany and Japan used millions of slave labourers;[71] Germany used about 12 million people, mostly from Eastern Europe,[47] while Japan used more than 18 million people in Far East Asia.[54][55]

Advances in technology and its application

[edit]

Aircraft were used for reconnaissance, as fighters, bombers, and ground-support, and each role developed considerably. Innovations included airlift (the capability to quickly move limited high-priority supplies, equipment, and personnel);[72] and strategic bombing (the bombing of enemy industrial and population centres to destroy the enemy's ability to wage war).[73] Anti-aircraft weaponry also advanced, including defences such as radar and surface-to-air artillery. The use of the jet aircraft was pioneered and, though late introduction meant it had little impact, it led to jets becoming standard in air forces worldwide.[74]

Advances were made in nearly every aspect of naval warfare, most notably with aircraft carriers and submarines. Although aeronautical warfare had relatively little success at the start of the war, actions at Taranto, Pearl Harbor, and the Coral Sea established the carrier as the dominant capital ship (in place of the battleship).[75][76][77] In the Atlantic, escort carriers became a vital part of Allied convoys, increasing the effective protection radius and helping to close the Mid-Atlantic gap.[78] Carriers were also more economical than battleships because of the relatively low cost of aircraft[79] and their not requiring to be as heavily armoured.[80] Submarines, which had proved to be an effective weapon during the First World War,[81] were expected by all combatants to be important in the second. The British focused development on anti-submarine weaponry and tactics, such as sonar and convoys, while Germany focused on improving its offensive capability, with designs such as the Type VII submarine and wolfpack tactics.[82][better source needed] Gradually, improving Allied technologies such as the Leigh light, hedgehog, squid, and homing torpedoes proved effective against German submarines.[83]

Land warfare changed from the static front-lines of trench warfare of World War I, which had relied on improved artillery that outmatched the speed of both infantry and cavalry, to increased mobility and combined arms. The tank, which had been used predominantly for infantry support in the First World War, had evolved into the primary weapon.[84] In the late 1930s, tank design was considerably more advanced than it had been during World War I,[85] and advances continued throughout the war with increases in speed, armour and firepower.[86][87] At the start of the war, most commanders thought enemy tanks should be met by tanks with superior specifications.[88] This idea was challenged by the poor performance of the relatively light early tank guns against armour, and German doctrine of avoiding tank-versus-tank combat. This, along with Germany's use of combined arms, were among the key elements of their highly successful blitzkrieg tactics across Poland and France.[84] Many means of destroying tanks, including indirect artillery, anti-tank guns (both towed and self-propelled), mines, short-ranged infantry antitank weapons, and other tanks were used.[88] Even with large-scale mechanisation, infantry remained the backbone of all forces,[89] and throughout the war, most infantry were equipped similarly to World War I.[90] The portable machine gun spread, a notable example being the German MG 34, and various submachine guns which were suited to close combat in urban and jungle settings.[90] The assault rifle, a late war development incorporating many features of the rifle and submachine gun, became the standard post-war infantry weapon for most armed forces.[91]

Most major belligerents attempted to solve the problems of complexity and security involved in using large codebooks for cryptography by designing ciphering machines, the most well known being the German Enigma machine.[92] Development of SIGINT (signals intelligence) and cryptanalysis enabled the countering process of decryption. Notable examples were the Allied decryption of Japanese naval codes[93] and British Ultra, a pioneering method for decoding Enigma benefiting from information given to the United Kingdom by the Polish Cipher Bureau, which had been decoding early versions of Enigma before the war.[94] Another aspect of military intelligence was the use of deception, which the Allies used to great effect, such as in operations Mincemeat and Bodyguard.[93][95]

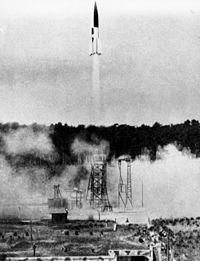

Other technological and engineering feats achieved during, or as a result of, the war include the world's first programmable computers (Z3, Colossus, and ENIAC), guided missiles and modern rockets, the Manhattan Project's development of nuclear weapons, operations research, the development of artificial harbours and oil pipelines under the English Channel.[96] Penicillin was first developed, mass-produced and used during the war.[97]

See also

[edit]- [[Archivo:

- REDIRECCIÓN Plantilla:Iconos|20px|Ver el portal sobre World War II]] Portal:World War II. Contenido relacionado con World.

- Lists of World War II topics

- Opposition to World War II

- Outline of World War II

- Lists of World War II military equipment

Notes

[edit]Citations

[edit]References

[edit]- Adamthwaite, Anthony P. (1992). The Making of the Second World War. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-90716-3.

- Anderson, Irvine H. Jr. (1975). "The 1941 De Facto Embargo on Oil to Japan: A Bureaucratic Reflex". The Pacific Historical Review. 44 (2): 201–231. doi:10.2307/3638003. JSTOR 3638003.

- Applebaum, Anne (2003). Gulag: A History of the Soviet Camps. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-7139-9322-6.

- ——— (2012). Iron Curtain: The Crushing of Eastern Europe 1944–56. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-7139-9868-9.

- Bacon, Edwin (1992). "Glasnost' and the Gulag: New Information on Soviet Forced Labour around World War II". Soviet Studies. 44 (6): 1069–1086. doi:10.1080/09668139208412066. JSTOR 152330.

- Badsey, Stephen (1990). Normandy 1944: Allied Landings and Breakout. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85045-921-0.

- Balabkins, Nicholas (1964). Germany Under Direct Controls: Economic Aspects of Industrial Disarmament 1945–1948. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-0449-0.

- Barber, John; Harrison, Mark (2006). "Patriotic War, 1941–1945". In Ronald Grigor Suny (ed.). The Cambridge History of Russia. Vol. III: The Twentieth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 217–242. ISBN 978-0-521-81144-6.

- Barker, A.J. (1971). The Rape of Ethiopia 1936. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-02462-6.

- Beevor, Antony (1998). Stalingrad. New York: Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-87095-0.

- ——— (2012). The Second World War. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-84497-6.

- Belco, Victoria (2010). War, Massacre, and Recovery in Central Italy: 1943–1948. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-9314-1.

- Bellamy, Chris T. (2007). Absolute War: Soviet Russia in the Second World War. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-375-41086-4.

- Ben-Horin, Eliahu (1943). The Middle East: Crossroads of History. New York: W.W. Norton.

- Berend, Ivan T. (1996). Central and Eastern Europe, 1944–1993: Detour from the Periphery to the Periphery. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-55066-6.

- Bernstein, Gail Lee (1991). Recreating Japanese Women, 1600–1945. Berkeley & Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-07017-2.

- Bilhartz, Terry D.; Elliott, Alan C. (2007). Currents in American History: A Brief History of the United States. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-1821-4.

- Bilinsky, Yaroslav (1999). Endgame in NATO's Enlargement: The Baltic States and Ukraine. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-96363-7.

- Bix, Herbert P. (2000). Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-019314-0.

- Black, Jeremy (2003). World War Two: A Military History. Abingdon & New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-30534-1.

- Blinkhorn, Martin (2006) [1984]. Mussolini and Fascist Italy (3rd ed.). Abingdon & New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-26206-4.

- Bonner, Kit; Bonner, Carolyn (2001). Warship Boneyards. Osceola, WI: MBI Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-7603-0870-7.

- Borstelmann, Thomas (2005). "The United States, the Cold War, and the colour line". In Melvyn P. Leffler; David S. Painter (eds.). Origins of the Cold War: An International History (2nd ed.). Abingdon & New York: Routledge. pp. 317–332. ISBN 978-0-415-34109-7.

- Bosworth, Richard; Maiolo, Joseph (2015). The Cambridge History of the Second World War Volume 2: Politics and Ideology. The Cambridge History of the Second World War (3 vol). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 313–314. Archived from the original on 20 August 2016. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- Brayley, Martin J. (2002). The British Army 1939–45, Volume 3: The Far East. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-238-8.

- British Bombing Survey Unit (1998). The Strategic Air War Against Germany, 1939–1945. London & Portland, OR: Frank Cass Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7146-4722-7.

- Brody, J. Kenneth (1999). The Avoidable War: Pierre Laval and the Politics of Reality, 1935–1936. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7658-0622-2.

- Brown, David (2004). The Road to Oran: Anglo-French Naval Relations, September 1939 – July 1940. London & New York: Frank Cass. ISBN 978-0-7146-5461-4.

- Buchanan, Andrew. "Globalizing the Second World War," Past and Present no. 258 (February 2023): 246-281. online; also see online review

- Buchanan, Tom (2006). Europe's Troubled Peace, 1945–2000. Oxford & Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-22162-3.

- Bueno de Mesquita, Bruce; Smith, Alastair; Siverson, Randolph M.; Morrow, James D. (2003). The Logic of Political Survival. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-02546-1.

- Bull, Martin J.; Newell, James L. (2005). Italian Politics: Adjustment Under Duress. Polity. ISBN 978-0-7456-1298-0.

- Bullock, Alan (1990). Hitler: A Study in Tyranny. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-013564-0.

- Burcher, Roy; Rydill, Louis (1995). Concepts in Submarine Design. Vol. 62. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 268. Bibcode:1995JAM....62R.268B. doi:10.1115/1.2895927. ISBN 978-0-521-55926-3.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Busky, Donald F. (2002). Communism in History and Theory: Asia, Africa, and the Americas. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0-275-97733-7.

- Canfora, Luciano (2006) [2004]. Democracy in Europe: A History. Oxford & Malden MA: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-1131-7.

- Cantril, Hadley (1940). "America Faces the War: A Study in Public Opinion". Public Opinion Quarterly. 4 (3): 387–407. doi:10.1086/265420. JSTOR 2745078.

- Chang, Iris (1997). The Rape of Nanking: The Forgotten Holocaust of World War II. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-06835-7.

- Christofferson, Thomas R.; Christofferson, Michael S. (2006). France During World War II: From Defeat to Liberation. New York: Fordham University Press. ISBN 978-0-8232-2562-0.

- Chubarov, Alexander (2001). Russia's Bitter Path to Modernity: A History of the Soviet and Post-Soviet Eras. London & New York: Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8264-1350-5.

- Ch'i, Hsi-Sheng (1992). "The Military Dimension, 1942–1945". In James C. Hsiung; Steven I. Levine (eds.). China's Bitter Victory: War with Japan, 1937–45. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe. pp. 157–184. ISBN 978-1-56324-246-5.

- Cienciala, Anna M. (2010). "Another look at the Poles and Poland during World War II". The Polish Review. 55 (1): 123–143. doi:10.2307/25779864. JSTOR 25779864. S2CID 159445902.

- Clogg, Richard (2002). A Concise History of Greece (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-80872-9.

- Coble, Parks M. (2003). Chinese Capitalists in Japan's New Order: The Occupied Lower Yangzi, 1937–1945. Berkeley & Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-23268-6.

- Collier, Paul (2003). The Second World War (4): The Mediterranean 1940–1945. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-539-6.

- Collier, Martin; Pedley, Philip (2000). Germany 1919–45. Oxford: Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-435-32721-7.

- Commager, Henry Steele (2004). The Story of the Second World War. Brassey's. ISBN 978-1-57488-741-9.

- Coogan, Anthony (1993). "The Volunteer Armies of Northeast China". History Today. 43. Archived from the original on 11 May 2012. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- Cook, Chris; Bewes, Diccon (1997). What Happened Where: A Guide to Places and Events in Twentieth-Century History. London: UCL Press. ISBN 978-1-85728-532-1.

- Cowley, Robert; Parker, Geoffrey, eds. (2001). The Reader's Companion to Military History. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 978-0-618-12742-9.

- Darwin, John (2007). After Tamerlane: The Rise & Fall of Global Empires 1400–2000. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-101022-9.

- Davies, Norman (2006). Europe at War 1939–1945: No Simple Victory. London: Macmillan. ix+544 pages. ISBN 978-0-333-69285-1. OCLC 70401618.

- Dear, I.C.B.; Foot, M.R.D., eds. (2001) [1995]. The Oxford Companion to World War II. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860446-4.

- DeLong, J. Bradford; Eichengreen, Barry (1993). "The Marshall Plan: History's Most Successful Structural Adjustment Program". In Rudiger Dornbusch; Wilhelm Nölling; Richard Layard (eds.). Postwar Economic Reconstruction and Lessons for the East Today. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. pp. 189–230. ISBN 978-0-262-04136-2.

- Dower, John W. (1986). War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War. New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-0-394-50030-0.

- Drea, Edward J. (2003). In the Service of the Emperor: Essays on the Imperial Japanese Army. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-6638-4.

- de Grazia, Victoria; Paggi, Leonardo (Autumn 1991). "Story of an Ordinary Massacre: Civitella della Chiana, 29 June, 1944". Cardozo Studies in Law and Literature. 3 (2): 153–169. doi:10.1525/lal.1991.3.2.02a00030. JSTOR 743479.

- Dunn, Dennis J. (1998). Caught Between Roosevelt & Stalin: America's Ambassadors to Moscow. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-2023-2.

- Eastman, Lloyd E. (1986). "Nationalist China during the Sino-Japanese War 1937–1945". In John K. Fairbank; Denis Twitchett (eds.). The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 13: Republican China 1912–1949, Part 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-24338-4.

- Ellman, Michael (2002). "Soviet Repression Statistics: Some Comments" (PDF). Europe-Asia Studies. 54 (7): 1151–1172. doi:10.1080/0966813022000017177. JSTOR 826310. S2CID 43510161. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 November 2012. Copy

- ———; Maksudov, S. (1994). "Soviet Deaths in the Great Patriotic War: A Note" (PDF). Europe-Asia Studies. 46 (4): 671–680. doi:10.1080/09668139408412190. JSTOR 152934. PMID 12288331. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 February 2022. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- Emadi-Coffin, Barbara (2002). Rethinking International Organization: Deregulation and Global Governance. London & New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-19540-9.

- Erickson, John (2001). "Moskalenko". In Shukman, Harold [in Russian] (ed.). Stalin's Generals. London: Phoenix Press. pp. 137–154. ISBN 978-1-84212-513-7.

- ——— (2003). The Road to Stalingrad. London: Cassell Military. ISBN 978-0-304-36541-8.

- Evans, David C.; Peattie, Mark R. (2012) [1997]. Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics, and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-244-7.

- Evans, Richard J. (2008). The Third Reich at War. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-7139-9742-2.

- Fairbank, John King; Goldman, Merle (2006) [1994]. China: A New History (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01828-0.

- Farrell, Brian P. (1993). "Yes, Prime Minister: Barbarossa, Whipcord, and the Basis of British Grand Strategy, Autumn 1941". Journal of Military History. 57 (4): 599–625. doi:10.2307/2944096. JSTOR 2944096.

- Ferguson, Niall (2006). The War of the World: Twentieth-Century Conflict and the Descent of the West. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-311239-6.

- Forrest, Glen; Evans, Anthony; Gibbons, David (2012). The Illustrated Timeline of Military History. New York: The Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-4488-4794-5.

- Förster, Jürgen (1998). "Hitler's Decision in Favour of War". In Horst Boog; Jürgen Förster; Joachim Hoffmann; Ernst Klink; Rolf-Dieter Muller; Gerd R. Ueberschar (eds.). Germany and the Second World War. Vol. IV: The Attack on the Soviet Union. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 13–52. ISBN 978-0-19-822886-8.

- Förster, Stig; Gessler, Myriam (2005). "The Ultimate Horror: Reflections on Total War and Genocide". In Roger Chickering; Stig Förster; Bernd Greiner (eds.). A World at Total War: Global Conflict and the Politics of Destruction, 1937–1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 53–68. ISBN 978-0-521-83432-2.

- Frei, Norbert (2002). Adenauer's Germany and the Nazi Past: The Politics of Amnesty and Integration. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-11882-8.

- Gardiner, Robert; Brown, David K., eds. (2004). The Eclipse of the Big Gun: The Warship 1906–1945. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-953-9.

- Garver, John W. (1988). Chinese-Soviet Relations, 1937–1945: The Diplomacy of Chinese Nationalism. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-505432-3.

- Gilbert, Martin (1989). Second World War. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-79616-9.

- Glantz, David M. (1986). "Soviet Defensive Tactics at Kursk, July 1943". Combined Arms Research Library. CSI Report No. 11. Command and General Staff College. OCLC 278029256. Archived from the original on 6 March 2008. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- ——— (1989). Soviet Military Deception in the Second World War. Abingdon & New York: Frank Cass. ISBN 978-0-7146-3347-3.

- ——— (1998). When Titans Clashed: How the Red Army Stopped Hitler. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-0899-7.

- ——— (2001). "The Soviet-German War 1941–45 Myths and Realities: A Survey Essay" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 July 2011.

- ——— (2002). The Battle for Leningrad: 1941–1944. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-1208-6.

- ——— (2005). "August Storm: The Soviet Strategic Offensive in Manchuria". Combined Arms Research Library. Leavenworth Papers. Command and General Staff College. OCLC 78918907. Archived from the original on 2 March 2008. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- Goldstein, Margaret J. (2004). World War II: Europe. Minneapolis: Lerner Publications. ISBN 978-0-8225-0139-8.

- Gordon, Andrew (2004). "The greatest military armada ever launched". In Jane Penrose (ed.). The D-Day Companion. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. pp. 127–144. ISBN 978-1-84176-779-6.

- Gordon, Robert S.C. (2012). The Holocaust in Italian Culture, 1944–2010. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-6346-2.

- Grove, Eric J. (1995). "A Service Vindicated, 1939–1946". In J.R. Hill (ed.). The Oxford Illustrated History of the Royal Navy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 348–380. ISBN 978-0-19-211675-8.

- Hane, Mikiso (2001). Modern Japan: A Historical Survey (3rd ed.). Boulder, CO: Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-3756-2.

- Hanhimäki, Jussi M. (1997). Containing Coexistence: America, Russia, and the "Finnish Solution". Kent, OH: Kent State University Press. ISBN 978-0-87338-558-9.

- Harris, Sheldon H. (2002). Factories of Death: Japanese Biological Warfare, 1932–1945, and the American Cover-up (2nd ed.). London & New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-93214-1.

- Harrison, Mark (1998). "The economics of World War II: an overview". In Mark Harrison (ed.). The Economics of World War II: Six Great Powers in International Comparison. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–42. ISBN 978-0-521-62046-8.

- Hart, Stephen; Hart, Russell; Hughes, Matthew (2000). The German Soldier in World War II. Osceola, WI: MBI Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-86227-073-2.

- Hauner, Milan (1978). "Did Hitler Want a World Dominion?". Journal of Contemporary History. 13 (1): 15–32. doi:10.1177/002200947801300102. JSTOR 260090. S2CID 154865385.

- Healy, Mark (1992). Kursk 1943: The Tide Turns in the East. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85532-211-0.

- Hearn, Chester G. (2007). Carriers in Combat: The Air War at Sea. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-3398-4.

- Hempel, Andrew (2005). Poland in World War II: An Illustrated Military History. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 978-0-7818-1004-3.

- Herbert, Ulrich (1994). "Labor as spoils of conquest, 1933–1945". In David F. Crew (ed.). Nazism and German Society, 1933–1945. London & New York: Routledge. pp. 219–273. ISBN 978-0-415-08239-6.

- Herf, Jeffrey (2003). "The Nazi Extermination Camps and the Ally to the East. Could the Red Army and Air Force Have Stopped or Slowed the Final Solution?". Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History. 4 (4): 913–930. doi:10.1353/kri.2003.0059. S2CID 159958616.

- Hill, Alexander (2005). The War Behind The Eastern Front: The Soviet Partisan Movement In North-West Russia 1941–1944. London & New York: Frank Cass. ISBN 978-0-7146-5711-0.

- Holland, James (2008). Italy's Sorrow: A Year of War 1944–45. London: HarperPress. ISBN 978-0-00-717645-8.

- Hosking, Geoffrey A. (2006). Rulers and Victims: The Russians in the Soviet Union. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02178-5.

- Howard, Joshua H. (2004). Workers at War: Labor in China's Arsenals, 1937–1953. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-4896-4.

- Hsu, Long-hsuen; Chang, Ming-kai (1971). History of The Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) (2nd ed.). Chung Wu Publishers. ASIN B00005W210. OCLC 12828898.[unreliable source?]

- Ingram, Norman (2006). "Pacifism". In Lawrence D. Kritzman; Brian J. Reilly (eds.). The Columbia History Of Twentieth-Century French Thought. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 76–78. ISBN 978-0-231-10791-4.

- Iriye, Akira (1981). Power and Culture: The Japanese-American War, 1941–1945. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-69580-1.

- Jackson, Ashley (2006). The British Empire and the Second World War. London & New York: Hambledon Continuum. ISBN 978-1-85285-417-1.

- Joes, Anthony James (2004). Resisting Rebellion: The History And Politics of Counterinsurgency. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-2339-4.

- Jowett, Philip S. (2001). The Italian Army 1940–45, Volume 2: Africa 1940–43. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85532-865-5.

- ———; Andrew, Stephen (2002). The Japanese Army, 1931–45. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-353-8.

- Jukes, Geoffrey (2001). "Kuznetzov". In Harold Shukman [in Russian] (ed.). Stalin's Generals. London: Phoenix Press. pp. 109–116. ISBN 978-1-84212-513-7.

- Kantowicz, Edward R. (1999). The Rage of Nations. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8028-4455-2.

- ——— (2000). Coming Apart, Coming Together. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8028-4456-9.

- Keeble, Curtis (1990). "The historical perspective". In Alex Pravda; Peter J. Duncan (eds.). Soviet-British Relations Since the 1970s. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-37494-1.

- Keegan, John (1997). The Second World War. London: Pimlico. ISBN 978-0-7126-7348-8.

- Kennedy, David M. (2001). Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929–1945. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514403-1.

- Kennedy-Pipe, Caroline (1995). Stalin's Cold War: Soviet Strategies in Europe, 1943–56. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-4201-0.

- Kershaw, Ian (2001). Hitler, 1936–1945: Nemesis. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-04994-7.

- ——— (2007). Fateful Choices: Ten Decisions That Changed the World, 1940–1941. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-7139-9712-5.

- Kitson, Alison (2001). Germany 1858–1990: Hope, Terror, and Revival. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-913417-5.

- Klavans, Richard A.; Di Benedetto, C. Anthony; Prudom, Melanie J. (1997). "Understanding Competitive Interactions: The U.S. Commercial Aircraft Market". Journal of Managerial Issues. 9 (1): 13–361. JSTOR 40604127.

- Kleinfeld, Gerald R. (1983). "Hitler's Strike for Tikhvin". Military Affairs. 47 (3): 122–128. doi:10.2307/1988082. JSTOR 1988082.

- Koch, H.W. (1983). "Hitler's 'Programme' and the Genesis of Operation 'Barbarossa'". The Historical Journal. 26 (4): 891–920. doi:10.1017/S0018246X00012747. JSTOR 2639289. S2CID 159671713.

- Kolko, Gabriel (1990) [1968]. The Politics of War: The World and United States Foreign Policy, 1943–1945. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-679-72757-6.

- Laurier, Jim (2001). Tobruk 1941: Rommel's Opening Move. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-092-6.

- Lee, En-han (2002). "The Nanking Massacre Reassessed: A Study of the Sino-Japanese Controversy over the Factual Number of Massacred Victims". In Robert Sabella; Fei Fei Li; David Liu (eds.). Nanking 1937: Memory and Healing. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe. pp. 47–74. ISBN 978-0-7656-0816-1.

- Leffler, Melvyn P.; Westad, Odd Arne, eds. (2010). The Cambridge History of the Cold War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83938-9, in 3 volumes.

- Levine, Alan J. (1992). The Strategic Bombing of Germany, 1940–1945. Westport, CT: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-275-94319-6.

- Lewis, Morton (1953). "Japanese Plans and American Defenses". In Greenfield, Kent Roberts (ed.). The Fall of the Philippines. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office. LCCN 53-63678. Archived from the original on 8 January 2012. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- Liberman, Peter (1996). Does Conquest Pay?: The Exploitation of Occupied Industrial Societies. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02986-3.

- Liddell Hart, Basil (1977). History of the Second World War (4th ed.). London: Pan. ISBN 978-0-330-23770-3.

- Lightbody, Bradley (2004). The Second World War: Ambitions to Nemesis. London & New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-22404-8.

- Lindberg, Michael; Todd, Daniel (2001). Brown-, Green- and Blue-Water Fleets: the Influence of Geography on Naval Warfare, 1861 to the Present. Westport, CT: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-275-96486-3.

- Lowe, C.J.; Marzari, F. (2002). Italian Foreign Policy 1870–1940. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-26681-9.

- Lynch, Michael (2010). The Chinese Civil War 1945–49. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-671-3.

- Maddox, Robert James (1992). The United States and World War II. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-0437-3.

- Maingot, Anthony P. (1994). The United States and the Caribbean: Challenges of an Asymmetrical Relationship. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-2241-4.

- Mandelbaum, Michael (1988). The Fate of Nations: The Search for National Security in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Cambridge University Press. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-521-35790-6.

- Marston, Daniel (2005). The Pacific War Companion: From Pearl Harbor to Hiroshima. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-882-3.

- Masaya, Shiraishi (1990). Japanese Relations with Vietnam, 1951–1987. Ithaca, NY: SEAP Publications. ISBN 978-0-87727-122-2.

- May, Ernest R. (1955). "The United States, the Soviet Union, and the Far Eastern War, 1941–1945". Pacific Historical Review. 24 (2): 153–174. doi:10.2307/3634575. JSTOR 3634575.

- Mazower, Mark (2008). Hitler's Empire: Nazi Rule in Occupied Europe. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-1-59420-188-2.

- Milner, Marc (1990). "The Battle of the Atlantic". In Gooch, John (ed.). Decisive Campaigns of the Second World War. Abingdon: Frank Cass. pp. 45–66. ISBN 978-0-7146-3369-5.

- Milward, A.S. (1964). "The End of the Blitzkrieg". The Economic History Review. 16 (3): 499–518. JSTOR 2592851.

- ——— (1992) [1977]. War, Economy, and Society, 1939–1945. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-03942-1.

- Minford, Patrick (1993). "Reconstruction and the UK Postwar Welfare State: False Start and New Beginning". In Rudiger Dornbusch; Wilhelm Nölling; Richard Layard (eds.). Postwar Economic Reconstruction and Lessons for the East Today. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. pp. 115–138. ISBN 978-0-262-04136-2.

- Mingst, Karen A.; Karns, Margaret P. (2007). United Nations in the Twenty-First Century (3rd ed.). Boulder, CO: Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-4346-4.

- Miscamble, Wilson D. (2007). From Roosevelt to Truman: Potsdam, Hiroshima, and the Cold War. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-86244-8.

- Mitcham, Samuel W. (2007) [1982]. Rommel's Desert War: The Life and Death of the Afrika Korps. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-3413-4.

- Mitter, Rana (2014). Forgotten Ally: China's World War II, 1937–1945. Mariner Books. ISBN 978-0-544-33450-2.

- Molinari, Andrea (2007). Desert Raiders: Axis and Allied Special Forces 1940–43. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84603-006-2.

- Murray, Williamson (1983). Strategy for Defeat: The Luftwaffe, 1933–1945. Maxwell Air Force Base, AL: Air University Press. ISBN 978-1-4294-9235-5. Archived from the original on 24 January 2022. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ———; Millett, Allan Reed (2001). A War to Be Won: Fighting the Second World War. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-00680-5.

- Myers, Ramon; Peattie, Mark (1987). The Japanese Colonial Empire, 1895–1945. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-10222-1.

- Naimark, Norman (2010). "The Sovietization of Eastern Europe, 1944–1953". In Melvyn P. Leffler; Odd Arne Westad (eds.). The Cambridge History of the Cold War. Vol. I: Origins. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 175–197. ISBN 978-0-521-83719-4.

- Neary, Ian (1992). "Japan". In Martin Harrop (ed.). Power and Policy in Liberal Democracies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 49–70. ISBN 978-0-521-34579-8.

- Neillands, Robin (2005). The Dieppe Raid: The Story of the Disastrous 1942 Expedition. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34781-7.

- Neulen, Hans Werner (2000). In the skies of Europe – Air Forces allied to the Luftwaffe 1939–1945. Ramsbury, Marlborough, UK: The Crowood Press. ISBN 1-86126-799-1.

- Niewyk, Donald L.; Nicosia, Francis (2000). The Columbia Guide to the Holocaust. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-11200-0.

- Overy, Richard (1994). War and Economy in the Third Reich. New York: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-820290-5.

- ——— (1995). Why the Allies Won. London: Pimlico. ISBN 978-0-7126-7453-9.

- ——— (2004). The Dictators: Hitler's Germany, Stalin's Russia. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-02030-4.

- ———; Wheatcroft, Andrew (1999). The Road to War (2nd ed.). London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-028530-7.

- O'Reilly, Charles T. (2001). Forgotten Battles: Italy's War of Liberation, 1943–1945. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-0195-7.

- Painter, David S. (2012). "Oil and the American Century". The Journal of American History. 99 (1): 24–39. doi:10.1093/jahist/jas073.

- Padfield, Peter (1998). War Beneath the Sea: Submarine Conflict During World War II. New York: John Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-24945-0.

- Pape, Robert A. (1993). "Why Japan Surrendered". International Security. 18 (2): 154–201. doi:10.2307/2539100. JSTOR 2539100. S2CID 153741180.

- Parker, Danny S. (2004). Battle of the Bulge: Hitler's Ardennes Offensive, 1944–1945 (New ed.). Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-81391-7.

- Payne, Stanley G. (2008). Franco and Hitler: Spain, Germany, and World War II. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12282-4.

- Perez, Louis G. (1998). The History of Japan. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-30296-1.

- Petrov, Vladimir (1967). Money and Conquest: Allied Occupation Currencies in World War II. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-0530-1.

- Polley, Martin (2000). An A–Z of Modern Europe Since 1789. London & New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-18597-4.

- Portelli, Alessandro (2003). The Order Has Been Carried Out: History, Memory, and Meaning of a Nazi Massacre in Rome. Basingstoke & New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-8008-3.

- Preston, P. W. (1998). Pacific Asia in the Global System: An Introduction. Oxford & Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 978-0-631-20238-7.

- Prins, Gwyn (2002). The Heart of War: On Power, Conflict and Obligation in the Twenty-First Century. London & New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-36960-2.

- Radtke, K.W. (1997). "'Strategic' concepts underlying the so-called Hirota foreign policy, 1933–7". In Aiko Ikeo (ed.). Economic Development in Twentieth Century East Asia: The International Context. London & New York: Routledge. pp. 100–120. ISBN 978-0-415-14900-6.

- Rahn, Werner (2001). "The War in the Pacific". In Horst Boog; Werner Rahn; Reinhard Stumpf; Bernd Wegner (eds.). Germany and the Second World War. Vol. VI: The Global War. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 191–298. ISBN 978-0-19-822888-2.

- Ratcliff, R.A. (2006). Delusions of Intelligence: Enigma, Ultra, and the End of Secure Ciphers. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85522-8.

- Read, Anthony (2004). The Devil's Disciples: Hitler's Inner Circle. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-04800-1.

- Read, Anthony; Fisher, David (2002) [1992]. The Fall Of Berlin. London: Pimlico. ISBN 978-0-7126-0695-0.

- Record, Jeffery (2005). Appeasement Reconsidered: Investigating the Mythology of the 1930s (PDF). Diane Publishing. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-58487-216-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 April 2010. Retrieved 15 November 2009.

- Rees, Laurence (2008). World War II Behind Closed Doors: Stalin, the Nazis and the West. London: BBC Books. ISBN 978-0-563-49335-8.

- Regan, Geoffrey (2004). The Brassey's Book of Military Blunders. Brassey's. ISBN 978-1-57488-252-0.

- Reinhardt, Klaus (1992). Moscow – The Turning Point: The Failure of Hitler's Strategy in the Winter of 1941–42. Oxford: Berg. ISBN 978-0-85496-695-0.

- Reynolds, David (2006). From World War to Cold War: Churchill, Roosevelt, and the International History of the 1940s. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-928411-5.

- Rich, Norman (1992) [1973]. Hitler's War Aims, Volume I: Ideology, the Nazi State, and the Course of Expansion. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-00802-9.

- Ritchie, Ella (1992). "France". In Martin Harrop (ed.). Power and Policy in Liberal Democracies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 23–48. ISBN 978-0-521-34579-8.

- Roberts, Cynthia A. (1995). "Planning for War: The Red Army and the Catastrophe of 1941". Europe-Asia Studies. 47 (8): 1293–1326. doi:10.1080/09668139508412322. JSTOR 153299.

- Roberts, Geoffrey (2006). Stalin's Wars: From World War to Cold War, 1939–1953. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11204-7.

- Roberts, J.M. (1997). The Penguin History of Europe. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-026561-3.

- Ropp, Theodore (2000). War in the Modern World (Revised ed.). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-6445-2.

- Roskill, S.W. (1954). The War at Sea 1939–1945, Volume 1: The Defensive. History of the Second World War. United Kingdom Military Series. London: HMSO. Archived from the original on 4 January 2022. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- Ross, Steven T. (1997). American War Plans, 1941–1945: The Test of Battle. Abingdon & New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7146-4634-3.

- Rottman, Gordon L. (2002). World War II Pacific Island Guide: A Geo-Military Study. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-31395-0.

- Rotundo, Louis (1986). "The Creation of Soviet Reserves and the 1941 Campaign". Military Affairs. 50 (1): 21–28. doi:10.2307/1988530. JSTOR 1988530.

- Salecker, Gene Eric (2001). Fortress Against the Sun: The B-17 Flying Fortress in the Pacific. Conshohocken, PA: Combined Publishing. ISBN 978-1-58097-049-5.

- Schain, Martin A., ed. (2001). The Marshall Plan Fifty Years Later. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-92983-4.

- Schmitz, David F. (2000). Henry L. Stimson: The First Wise Man. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8420-2632-1.

- Schoppa, R. Keith (2011). In a Sea of Bitterness, Refugees during the Sino-Japanese War. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-05988-7.

- Sella, Amnon (1978). ""Barbarossa": Surprise Attack and Communication". Journal of Contemporary History. 13 (3): 555–583. doi:10.1177/002200947801300308. JSTOR 260209. S2CID 220880174.

- ——— (1983). "Khalkhin-Gol: The Forgotten War". Journal of Contemporary History. 18 (4): 651–687. JSTOR 260307.

- Senn, Alfred Erich (2007). Lithuania 1940: Revolution from Above. Amsterdam & New York: Rodopi. ISBN 978-90-420-2225-6.

- Shaw, Anthony (2000). World War II: Day by Day. Osceola, WI: MBI Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-7603-0939-1.

- Shepardson, Donald E. (1998). "The Fall of Berlin and the Rise of a Myth". Journal of Military History. 62 (1): 135–154. doi:10.2307/120398. JSTOR 120398.

- Shirer, William L. (1990) [1960]. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-72868-7.

- Shore, Zachary (2003). What Hitler Knew: The Battle for Information in Nazi Foreign Policy. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-518261-3.

- Slim, William (1956). Defeat into Victory. London: Cassell. ISBN 978-0-304-29114-4.

- Smith, Alan (1993). Russia and the World Economy: Problems of Integration. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-08924-1.

- Smith, J.W. (1994). The World's Wasted Wealth 2: Save Our Wealth, Save Our Environment. Institute for Economic Democracy. ISBN 978-0-9624423-2-2.

- Smith, Peter C. (2002) [1970]. Pedestal: The Convoy That Saved Malta (5th ed.). Manchester: Goodall. ISBN 978-0-907579-19-9.

- Smith, David J.; Pabriks, Artis; Purs, Aldis; Lane, Thomas (2002). The Baltic States: Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-28580-3.

- Smith, Winston; Steadman, Ralph (2004). All Riot on the Western Front, Volume 3. Last Gasp. ISBN 978-0-86719-616-0.

- Snyder, Timothy (2010). Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. London: The Bodley Head. ISBN 978-0-224-08141-2.

- Spring, D. W. (1986). "The Soviet Decision for War against Finland, 30 November 1939". Soviet Studies. 38 (2): 207–226. doi:10.1080/09668138608411636. JSTOR 151203. S2CID 154270850.

- Steinberg, Jonathan (1995). "The Third Reich Reflected: German Civil Administration in the Occupied Soviet Union, 1941–4". The English Historical Review. 110 (437): 620–651. doi:10.1093/ehr/cx.437.620. JSTOR 578338.

- Steury, Donald P. (1987). "Naval Intelligence, the Atlantic Campaign and the Sinking of the Bismarck: A Study in the Integration of Intelligence into the Conduct of Naval Warfare". Journal of Contemporary History. 22 (2): 209–233. doi:10.1177/002200948702200202. JSTOR 260931. S2CID 159943895.

- Stueck, William (2010). "The Korean War". In Melvyn P. Leffler; Odd Arne Westad (eds.). The Cambridge History of the Cold War. Vol. I: Origins. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 266–287. ISBN 978-0-521-83719-4.

- Sumner, Ian; Baker, Alix (2001). The Royal Navy 1939–45. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-195-4.

- Swain, Bruce (2001). A Chronology of Australian Armed Forces at War 1939–45. Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-86508-352-0.

- Swain, Geoffrey (1992). "The Cominform: Tito's International?". The Historical Journal. 35 (3): 641–663. doi:10.1017/S0018246X00026017. S2CID 163152235.

- Tanaka, Yuki (1996). Hidden Horrors: Japanese War Crimes in World War II. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-2717-4.

- Taylor, A.J.P. (1961). The Origins of the Second World War. London: Hamish Hamilton.

- ——— (1979). How Wars Begin. London: Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 978-0-241-10017-2.

- Taylor, Jay (2009). The Generalissimo: Chiang Kai-shek and the Struggle for Modern China. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-03338-2.

- Thomas, Nigel; Andrew, Stephen (1998). German Army 1939–1945 (2): North Africa & Balkans. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85532-640-8.

- Thompson, John Herd; Randall, Stephen J. (2008). Canada and the United States: Ambivalent Allies (4th ed.). Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0-8203-3113-3.

- Trachtenberg, Marc (1999). A Constructed Peace: The Making of the European Settlement, 1945–1963. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-00273-6.

- Tucker, Spencer C.; Roberts, Priscilla Mary (2004). Encyclopedia of World War II: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-999-7.

- Umbreit, Hans (1991). "The Battle for Hegemony in Western Europe". In P. S. Falla (ed.). Germany and the Second World War. Vol. 2: Germany's Initial Conquests in Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 227–326. ISBN 978-0-19-822885-1.

- United States Army (1986) [1953]. The German Campaigns in the Balkans (Spring 1941). Washington, DC: Department of the Army. Archived from the original on 17 January 2022. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- Waltz, Susan (2002). "Reclaiming and Rebuilding the History of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights". Third World Quarterly. 23 (3): 437–448. doi:10.1080/01436590220138378. JSTOR 3993535. S2CID 145398136.

- Ward, Thomas A. (2010). Aerospace Propulsion Systems. Singapore: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-82497-9.

- Watson, William E. (2003). Tricolor and Crescent: France and the Islamic World. Westport, CT: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-275-97470-1.

- Weinberg, Gerhard L. (2005). A World at Arms: A Global History of World War II (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85316-3.; comprehensive overview with emphasis on diplomacy

- Wettig, Gerhard (2008). Stalin and the Cold War in Europe: The Emergence and Development of East-West Conflict, 1939–1953. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-5542-6.

- Wiest, Andrew; Barbier, M.K. (2002). Strategy and Tactics: Infantry Warfare. St Paul, MN: MBI Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-7603-1401-2.

- Williams, Andrew (2006). Liberalism and War: The Victors and the Vanquished. Abingdon & New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-35980-1.

- Wilt, Alan F. (1981). "Hitler's Late Summer Pause in 1941". Military Affairs. 45 (4): 187–191. doi:10.2307/1987464. JSTOR 1987464.

- Wohlstetter, Roberta (1962). Pearl Harbor: Warning and Decision. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-0597-4.

- Wolf, Holger C. (1993). "The Lucky Miracle: Germany 1945–1951". In Rudiger Dornbusch; Wilhelm Nölling; Richard Layard (eds.). Postwar Economic Reconstruction and Lessons for the East Today. Cambridge: MIT Press. pp. 29–56. ISBN 978-0-262-04136-2.

- Wood, James B. (2007). Japanese Military Strategy in the Pacific War: Was Defeat Inevitable?. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-5339-2.

- Yoder, Amos (1997). The Evolution of the United Nations System (3rd ed.). London & Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-56032-546-8.

- Zalampas, Michael (1989). Adolf Hitler and the Third Reich in American magazines, 1923–1939. Bowling Green University Popular Press. ISBN 978-0-87972-462-7.

- Zaloga, Steven J. (1996). Bagration 1944: The Destruction of Army Group Centre. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85532-478-7.

- ——— (2002). Poland 1939: The Birth of Blitzkrieg. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-408-5.

- Zeiler, Thomas W. (2004). Unconditional Defeat: Japan, America, and the End of World War II. Wilmington, DE: Scholarly Resources. ISBN 978-0-8420-2991-9.

- Zetterling, Niklas; Tamelander, Michael (2009). Bismarck: The Final Days of Germany's Greatest Battleship. Drexel Hill, PA: Casemate. ISBN 978-1-935149-04-0.

External links

[edit]- West Point Maps of the European War Archived 23 March 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- West Point Maps of the Asian-Pacific War Archived 23 March 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- Atlas of the World Battle Fronts (July 1943 to August 1945)

- Records of World War II propaganda posters are held by Simon Fraser University's Special Collections and Rare Books Archived 2 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- Maps of World War II in Europe at Omniatlas

Template:World War II Template:WWII history by nation Template:Western culture

- ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^ Förster & Gessler 2005, p. 64.

- ^ Ghuhl, Wernar (2007) Imperial Japan's World War Two Transaction Publishers pp. 7, 30

- ^ Polmar, Norman; Thomas B. Allen (1991) World War II: America at war, 1941–1945 ISBN 978-0-394-58530-7

- ^ ""Goak here": A.J.P. Taylor and 'The Origins of the Second World War.'". Canadian Journal of History. 1 August 1996.

- ^ Template:Harvnb; Template:Harvnb; Yisreelit, Hevrah Mizrahit (1965). Asian and African Studies, p. 191.

For 1941 see Template:Harvnb; Kellogg, William O (2003). American History the Easy Way. Barron's Educational Series. p. 236 ISBN 0-7641-1973-7.

There is also the viewpoint that both World War I and World War II are part of the same "European Civil War" or "Second Thirty Years War": Template:Harvnb; Template:Harvnb. - ^ Beevor 2012, p. 10.

- ^ "In Many Ways, Author Says, Spanish Civil War Was 'The First Battle Of WWII'". Fresh Air. NPR. 10 March 2017. Archived from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ Frank, Willard C. (1987). "The Spanish Civil War and the Coming of the Second World War". The International History Review. 9 (3): 368–409. doi:10.1080/07075332.1987.9640449. JSTOR 40105814. Archived from the original on 1 February 2022. Retrieved 17 February 2022 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Mark Kramer, "The Soviet Bloc and the Cold War in Europe," in Larresm, Klaus, ed. (2014). A Companion to Europe Since 1945. Wiley. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-118-89024-0.

- ^ Template:Harvnb.

- ^ Genzberger, Christine (1994). China Business: The Portable Encyclopedia for Doing Business with China. Petaluma, CA: World Trade Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-9631864-3-0.

- ^ Florida Center for Instructional Technology (2005). "Victims". A Teacher's Guide to the Holocaust. University of South Florida. Archived from the original on 16 May 2016. Retrieved 2 February 2008.

- ^ a b Template:Harvnb.

- ^ Snyder, Timothy (16 July 2009). "Holocaust: The Ignored Reality". The New York Review of Books. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- ^ "Polish Victims". www.ushmm.org. Archived from the original on 7 May 2016. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- ^ "Non-Jewish Holocaust Victims : The 5,000,000 others". BBC. April 2006. Archived from the original on 3 March 2013. Retrieved 4 August 2013.

- ^ Template:Harvnb.

- ^ Redžić, Enver (2005). Bosnia and Herzegovina in the Second World War. New York: Tylor and Francis. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-7146-5625-0. Archived from the original on 18 August 2021. Retrieved 18 August 2021.

- ^ Geiger, Vladimir (2012). "Human Losses of the Croats in World War II and the Immediate Post-War Period Caused by the Chetniks (Yugoslav Army in the Fatherand) and the Partisans (People's Liberation Army and the Partisan Detachments of Yugoslavia/Yugoslav Army) and the Communist Authorities: Numerical Indicators". Review of Croatian History. VIII (1). Croatian Institute of History: 117. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ^ Massacre, Volhynia. "The Effects of the Volhynian Massacres". Volhynia Massacre. Archived from the original on 21 June 2018. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- ^ "Od rzezi wołyńskiej do akcji Wisła. Konflikt polsko-ukraiński 1943–1947". dzieje.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on 24 June 2018. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ^ Rummell, R.J. "Statistics". Freedom, Democide, War. The University of Hawaii System. Archived from the original on 23 March 2010. Retrieved 25 January 2010.

- ^ Template:Harvnb.

- ^ Carmichael, Cathie; Maguire, Richard (2015). The Routledge History of Genocide. Routledge. p. 105. ISBN 978-0367867065.

- ^ "A Culture of Cruelty". HistoryNet. 6 November 2017. Archived from the original on 7 May 2022. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ Template:Harvnb.

- ^ Template:Harvnb.

- ^ Gold, Hal (1996). Unit 731 testimony. Tuttle. pp. 75–77. ISBN 978-0-8048-3565-7.

- ^ Template:Harvnb.

- ^ Template:Harvnb.

- ^ Template:Harvnb.

- ^ "Japan tested chemical weapons on Aussie POW: new evidence". The Japan Times Online. 27 July 2004. Archived from the original on 29 May 2012. Retrieved 25 January 2010.

- ^ Kużniar-Plota, Małgorzata (30 November 2004). "Decision to commence investigation into Katyn Massacre". Departmental Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes against the Polish Nation. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- ^ Robert Gellately (2007). Lenin, Stalin, and Hitler: The Age of Social Catastrophe. Knopf, ISBN 1-4000-4005-1 p. 391

- ^ Women and War. ABC-CLIO. 2006. pp. 480–. ISBN 978-1-85109-770-8.

- ^ Bird, Nicky (October 2002). "Berlin: The Downfall 1945 by Antony Beevor". International Affairs. 78 (4). Royal Institute of International Affairs: 914–916.

- ^ Norman M., Naimark, Norman M. (1995). The Russians in Germany: A History of the Soviet Zone of Occupation, 1945–1949. Cambridge: Belknap Press. p. 70.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zur Debatte um die Ausstellung Vernichtungskrieg. Verbrechen der Wehrmacht 1941–1944 im Kieler Landeshaus (Debate on the War of Extermination. Crimes of the Wehrmacht, 1941–1944) (PDF). Kiel. 1999.

- ^ Pascale R . Bos, "Feminists Interpreting the Politics of Wartime Rape: Berlin, 1945"; Yugoslavia, 1992–1993 Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 2006, vol. 31, no. 4, pp. 996–1025

- ^ Terror from the Sky: The Bombing of German Cities in World War II. Berghahn Books. 2010. p. 167. ISBN 978-1-84545-844-7.

- ^ John Dower (2007). "Lessons from Iwo Jima". Perspectives. 45 (6): 54–56. Archived from the original on 17 January 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2022.

- ^ Institute of National Remembrance, Polska 1939–1945 Straty osobowe i ofiary represji pod dwiema okupacjami. Materski and Szarota. p. 9 "Total Polish population losses under German occupation are currently calculated at about 2 770 000".

- ^ The World Must Know: The History of the Holocaust as Told in the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (2nd ed.), 2006. Washington, DC: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. ISBN 978-0801883583.

- ^ Template:Harvnb

- ^ Template:Harvnb.

- ^ a b Marek, Michael (27 October 2005). "Final Compensation Pending for Former Nazi Forced Laborers". dw-world.de. Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 2 May 2006. Retrieved 19 January 2010.

- ^ J. Arch Getty, Gábor T. Rittersporn and Viktor N. Zemskov. Victims of the Soviet Penal System in the Pre-War Years: A First Approach on the Basisof Archival Evidence. The American Historical Review, Vol. 98, No. 4 (Oct. 1993), pp. 1017–49

- ^ Template:Harvnb.

- ^ Zemskov V.N. On repatriation of Soviet citizens. Istoriya SSSR., 1990, No. 4, (in Russian). See also [1] Archived 14 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine (online version), and Template:Harvnb; Template:Harvnb.

- ^ "Japanese Atrocities in the Philippines". American Experience: the Bataan Rescue. PBS Online. Archived from the original on 27 July 2003. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- ^ Template:Harvnb.

- ^ Template:Harvnb.

- ^ a b Ju, Zhifen (June 2002). "Japan's Atrocities of Conscripting and Abusing North China Draftees after the Outbreak of the Pacific War". Joint Study of the Sino-Japanese War: Minutes of the June 2002 Conference. Harvard University Faculty of Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on 21 May 2012. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

- ^ a b "Indonesia: World War II and the Struggle For Independence, 1942–50; The Japanese Occupation, 1942–45". Library of Congress. 1992. Archived from the original on 30 October 2004. Retrieved 9 February 2007.

- ^ Template:Harvnb.

- ^ Template:Harvnb.

- ^ Template:Harvnb.

- ^ Template:Harvnb.

- ^ Template:Harvnb.

- ^ Template:Harvnb

- ^ Template:Harvnb.

- ^ a b Template:Harvnb.

- ^ a b Template:Harvnb.

- ^ Compare:

Wilson, Mark R. (2016). Destructive Creation: American Business and the Winning of World War II. American Business, Politics, and Society (reprint ed.). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-8122-9354-8. Archived from the original on 22 November 2020. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

By producing nearly two thirds of the munitions used by Allied forces – including huge numbers of aircraft, ships, tanks, trucks, rifles, artillery shells, and bombs – American industry became what President Franklin D. Roosevelt once called 'the arsenal of democracy' [...].

- ^ Template:Harvnb.

- ^ Template:Harvnb.

- ^ Griffith, Charles (1999). The Quest: Haywood Hansell and American Strategic Bombing in World War II. Diane Publishing. p. 203. ISBN 978-1-58566-069-8.

- ^ Template:Harvnb.

- ^ Template:Harvnb; Template:Harvnb..

- ^ Unidas, Naciones (2005). World Economic And Social Survey 2004: International Migration. United Nations Pubns. p. 23. ISBN 978-92-1-109147-2.

- ^ Template:Harvnb.

- ^ Template:Harvnb.

- ^ Template:Harvnb; Template:Harvnb.

- ^ Template:Harvnb.

- ^ Bishop, Chris; Chant, Chris (2004). Aircraft Carriers: The World's Greatest Naval Vessels and Their Aircraft. Wigston, Leics: Silverdale Books. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-84509-079-1.

- ^ Chenoweth, H. Avery; Nihart, Brooke (2005). Semper Fi: The Definitive Illustrated History of the U.S. Marines. New York: Main Street. p. 180. ISBN 978-1-4027-3099-3.

- ^ Template:Harvnb.

- ^ Template:Harvnb.

- ^ Template:Harvnb.

- ^ Template:Harvnb.

- ^ Template:Harvnb.

- ^ Burns, R. W. (September 1994). "Impact of technology on the defeat of the U-boat September 1939 – May 1943". IEE Proceedings – Science, Measurement and Technology. 141 (5): 343–355. doi:10.1049/ip-smt:19949918.

- ^ a b Template:Harvnb.

- ^ Dupuy, Trevor Nevitt (1982). The Evolution of Weapons and Warfare. Jane's Information Group. p. 231. ISBN 978-0-7106-0123-0.

- ^ "The Vital Role Of Tanks In The Second World War". Imperial War Museums. Archived from the original on 25 March 2022. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ Castaldi, Carolina; Fontana, Roberto; Nuvolari, Alessandro (1 August 2009). "'Chariots of fire': the evolution of tank technology, 1915–1945". Journal of Evolutionary Economics. 19 (4): 545–566. doi:10.1007/s00191-009-0141-0. ISSN 1432-1386. S2CID 36789517.

- ^ a b Template:Harvnb.

- ^ Template:Harvnb.

- ^ a b Template:Harvnb.

- ^ Sprague, Oliver; Griffiths, Hugh (2006). "The AK-47: the worlds favourite killing machine" (PDF). controlarms.org. p. 1. Archived from the original on 28 December 2018. Retrieved 14 November 2009.

- ^ Template:Harvnb.

- ^ a b Schoenherr, Steven (2007). "Code Breaking in World War I". History Department at the University of San Diego. Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 15 November 2009.

- ^ Macintyre, Ben (10 December 2010). "Bravery of thousands of Poles was vital in securing victory". The Times. London. p. 27. Template:Gale.

- ^ Rowe, Neil C.; Rothstein, Hy. "Deception for Defense of Information Systems: Analogies from Conventional Warfare". Departments of Computer Science and Defense Analysis U.S. Naval Postgraduate School. Air University. Archived from the original on 23 November 2010. Retrieved 15 November 2009.

- ^ "World War – II". InsightsIAS. Archived from the original on 11 July 2022. Retrieved 17 September 2022.

- ^ "Discovery and Development of Penicillin: International Historic Chemical Landmark". Washington, DC: American Chemical Society. Archived from the original on 28 June 2019. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- Pages using the JsonConfig extension

- حوالہ جات میں غلطیوں کے ساتھ صفحات

- Pages with graphs

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with specifically marked weasel-worded phrases from December 2019

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- All articles lacking reliable references

- Articles lacking reliable references from July 2020

- CS1: long volume value

- CS1 errors: periodical ignored

- Articles lacking reliable references from November 2021

- Pages using Sister project links with default search

- Webarchive template wayback links

- World War II

- World Wars

- Conflicts in 1939

- Conflicts in 1940

- Conflicts in 1941

- Conflicts in 1942

- Conflicts in 1943

- Conflicts in 1944

- Conflicts in 1945

- Global conflicts

- Late modern Europe

- Nuclear warfare

- War

- Wars involving Albania

- Wars involving Australia

- Wars involving Austria

- Wars involving Belgium

- Wars involving Bolivia

- Wars involving Brazil

- Wars involving British India

- Wars involving Bulgaria

- Wars involving Myanmar

- Wars involving Cambodia

- Wars involving Canada

- Wars involving Chile

- Wars involving Colombia

- Wars involving Costa Rica

- Wars involving Croatia

- Wars involving Cuba

- Wars involving Czechoslovakia

- Wars involving Denmark

- Wars involving the Dominican Republic

- Wars involving Ecuador

- Wars involving Egypt

- Wars involving El Salvador

- Wars involving Estonia

- Wars involving Ethiopia

- Wars involving Finland

- Wars involving France

- Wars involving Germany

- Wars involving Greece

- Wars involving Guatemala

- Wars involving Haiti

- Wars involving Honduras

- Wars involving Hungary

- Wars involving Iceland

- Wars involving Indonesia

- Wars involving Italy

- Wars involving Iran

- Wars involving Iraq

- Wars involving Japan

- Wars involving Kazakhstan

- Wars involving Laos

- Wars involving Latvia

- Wars involving Lebanon

- Wars involving Liberia

- Wars involving Lithuania

- Wars involving Luxembourg

- Wars involving Mexico

- Wars involving Mongolia

- Wars involving Montenegro

- Wars involving Nepal

- Wars involving Norway

- Wars involving Nicaragua

- Wars involving Panama

- Wars involving Paraguay

- Wars involving Peru

- Wars involving Poland

- Wars involving Rhodesia

- Wars involving Romania

- Wars involving Saudi Arabia

- Wars involving Serbia

- Wars involving Slovakia

- Wars involving Slovenia

- Wars involving South Africa

- Wars involving Sri Lanka

- Wars involving Syria

- Wars involving Thailand

- Wars involving the Netherlands

- Wars involving the Philippines

- Wars involving the Republic of China

- Wars involving the Soviet Union

- Wars involving the United Kingdom

- Wars involving the United States

- Wars involving Uruguay

- Wars involving Venezuela

- Wars involving Vietnam

- Wars involving Yugoslavia

- Wars involving India

- CS1 errors: empty citation

- CS1 Polish-language sources (pl)

- CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list