Pornography

Pornography (colloquially known as porn or porno) has been defined as sexual subject material "such as a picture, video, or text," that is considered sexually arousing.[a] Indicated for the consumption by adults, pornography depictions have evolved from cave paintings, some forty millennia ago, to virtual reality presentations in modern-day. Pornography use is considered a widespread recreational activity among people in-line with other digitally mediated activities such as use of social media or video games.[b] A distinction is often made regarding adult content as whether to classify it as pornography or erotica.

The oldest artifacts that are considered pornographic were discovered in Germany in 2008 CE and are dated to be at least 35,000 years old.[c] Throughout the history of erotic depictions, various people have regarded them as noxious and made attempts to suppress them under obscenity laws, censor, or make them illegal. Such grounds and even the definition of pornography have differed in various historical, cultural, and national contexts.[4] The Indian Sanskrit text Kama Sutra (3rd century CE), contained prose, poetry, and illustrations regarding sexual behavior, and the book was celebrated; while the British English text Fanny Hill (1748), considered "the first original English prose pornography,"[5] has been one of the most prosecuted and banned books. In the late 19th century, a film by Thomas Edison that depicted a kiss was denounced as obscene in the United States, whereas Eugène Pirou's 1896 film Bedtime for the Bride was received very favorably in France. Starting from the mid-twentieth century on, societal attitudes towards sexuality became more lenient in the Western world where legal definitions of obscenity were made limited. In 1969, Blue Movie became the first film to depict unsimulated sex that received a wide theatrical release in the United States. This was followed by the "Golden Age of Porn" (1969–1984). The introduction of home video and the World Wide Web in the late 20th century led to global growth in the pornography business. Starting in the 21st century, greater access to the internet and affordable smartphones made pornography more mainstream.

Pornography has been notable for providing a safe outlet to sexual desires that may not be satisfied within relationships and for being a facilitator of sexual release in people who cannot or do not want to have a partner. It is often equated with Journalism as both offer a view into the unknown or the hidden aspects of people. Research has suggested four broad motivations in people for using pornography, namely: "using pornography for fantasy, habitual use, mood management, and as part of a relationship." Studies have indicated that sexual function defined as "a person's ability to respond sexually or to experience sexual pleasure," is better in women who consume pornography frequently than in women who do not; no such association had been noticed in men. Pornography has been found to serve the purpose of an anti-depressant for the unhappy. As for pornography use to have any implication on public health, scholars have stated that pornography use does not meet the definition of a public health crisis. People who regard porn as sex education material were identified as being more likely to not use condoms in their own sex lives, a risky behaviour that is warned against considering performers working for pornographic studios undergo regular testing for sexually transmitted infections every two weeks, unlike much of the general public. Comparative studies have found that higher "pornography consumption" and "pornography tolerance" among people to be associated with their greater support for gender equality; those who support regulated pornography were distinguished as being more egalitarian than those who support a pornography ban. While some feminist groups sought to abolish pornography believing it to be harmful, other feminist groups have opposed censorship efforts insisting pornography is benign. A longitudinal study has ascertained that pornography use could not be a contributing factor in intimate partner violence.[d]

Called an "erotic engine,"[7] pornography has been noted for its key role in the development of various communication and media processing technologies. By being an early adopter of innovations ahead of other industries and as a provider of financial capital, the pornography industry has been cited to be a contributing factor in the adoption and popularization of many technologies. The accurate economic size of the porn industry in the early twenty-first century is unknown. Kassia Wosick, a sociologist from New Mexico State University, estimated the worldwide market value of porn to be at US$97 billion in 2015, with the US revenue estimated between $10 and $12 billion. IBISWorld, a leading industry market researcher, projected the total US revenue to reach US$3.3 billion in the year 2020. In 2018, pornography in Japan was estimated to be worth over $20 billion. The US pornography industry employs numerous performers along with production and support staff, and has its own industry-specific publications: XBIZ and AVN; a trade association, the Free Speech Coalition; and award shows, XBIZ Awards and AVN Awards. From the mid 2010s, unscrupulous pornography such as deepfake pornography and revenge porn have become issues of concern.

Etymology and definition

[edit]The word pornography is a conglomerate of two ancient Greek words: πόρνος (pórnos) "fornicators," and γράφειν (gráphein) "writing, recording, or description."[8][9] In Greek language, the term pornography connotes depiction of sexual activity.[10]

The term porn is an abbreviation of pornography.[10] The related term πόρνη (pórnē) "prostitute" in Greek, originally meant "bought, purchased" similar to pernanai "to sell," from the proto-Indo-European root per-, "to hand over" – alluding to the notion of selling. In ancient Greece a brothel was called a "porneion".[10] No date is known for the first use of the word pornography in Greek; the earliest attested, most related word one could find in Greek is πορνογράφος (pornográphos), i.e. "someone writing about harlots" in the 3rd century CE work Deipnosophists by Athenaeus.[11][12] The oldest published reference to the term pornography as in 'new pornographie,' is dated back to 1638 and is credited to Nathaniel Butter in a history of the Fleet newspaper industry.[13]

The Modern Greek word pornographia (πορνογραφία) is a reborrowing of the French "pornographie,"[14] which was in use in the French language during the 1800s. The word did not enter the English language as the familiar word until 1847[15] or as a French import in New Orleans in 1842.[16] The word was originally introduced by classical scholars as "a bookish, and therefore nonoffensive, term for writing about prostitutes",[17] but its meaning was quickly expanded to include all forms of "objectionable or obscene material in art and literature."[17] In 1864, Webster's Dictionary published the meaning for the word pornography as "a licentious painting,"[17] and the Oxford English Dictionary as: "obscene painting" (1842), "description of obscene matters, obscene publication" (1977 or earlier).[18]

Another term generally used to identify sexual material is erotica. Sometimes used as a synonym for "pornography," "erotica" is derived from the feminine form of the ancient Greek adjective: ἐρωτικός (erōtikós), from ἔρως (érōs)—words used to indicate lust, and sexual love.[17]

Definitions for the term "pornography" are varied, with people from both pro- and anti-pornography groups defining it either favorably or unfavourably, thus making any definition of the term "pornography" very stipulative.[19][20] Nevertheless, academic researchers have defined pornography as sexual subject material "such as a picture, video, or text," that is primarily intended to assist sexual arousal in the consumer and is made and supplied with "the consent of all persons involved."[a] Arousal is considered the primary objective, the raison d'etre, that a material must fulfill for it to be treated as pornographic. As some people can feel aroused by an image that is not meant to be sexually arousing and conversely cannot feel aroused by material that is clearly intended for arousal, the material that can be considered as pornography becomes subjective.[21]

In 1964, when the US Supreme Court faced a controversy over whether Louis Malle's French film, The Lovers, violated the First Amendment prohibition against obscene speech, Justice Potter Stewart, in determining what exactly distinguishes pornography from obscenity, famously stated that he could never certainly succeed in precisely defining porn but knew what counts as porn when he encounters it: "I know it when I see it," he said.[22]

Pornography throughout history

[edit]

Pornography from ancient times

[edit]Depictions of a sexual nature have existed since prehistoric times, as seen in the venus figurines and rock art.[23] People across various civilizations have created works that depicted explicit sex; these works included artifacts, music, poetry, and murals among other things that are often interwined with religious and supernatural themes.[24] The oldest artifacts, including a venus figurine, which are considered to be pornographic were discovered in 2008 CE at a cave near Stuttgart in Germany, radiocarbon dating suggests they are at least 35,000 years old, belonging to the aurignacian period.[c] Vast number of artifacts have been discovered from ancient mesopotamia that had depictions of explicit heterosexual sex.[26][27]

Glyptic art from the Sumerian Early Dynastic Period frequently shows scenes of frontal sex in the missionary position.[26] In Mesopotamian votive plaques, from the early second millennium BCE, a man is usually shown penetrating a woman from behind while she bends over drinking beer through a straw.[26] Middle Assyrian lead votive figurines often represented a man standing and penetrating a woman as she rests on the top of an altar.[26] Scholars have traditionally interpreted all these depictions as scenes of hieros gamos (an ancient sacred marriage between a god and a goddess), but they are more likely to be associated with the cult of Inanna, the goddess of sex and prostitution.[26] Many sexually explicit images were found in the temple of Inanna at Assur, which also contained models of male and female sexual organs.[26]

Depictions of sexual intercourse were not part of the general repertory of ancient Egyptian formal art, but rudimentary sketches of heterosexual intercourse have been found on pottery fragments and in graffiti.[28] The final two thirds of the Turin Erotic Papyrus (Papyrus 55001), an Egyptian papyrus scroll discovered at Deir el-Medina,[29][28] consists of a series of twelve vignettes showing men and women in various sexual positions.[29] The scroll was probably painted in the Ramesside period (1292–1075 BCE) and its high artistic quality indicates that it was produced for a wealthy audience.[29] No other similar scrolls have yet been discovered.[28]

pornography is sometimes characterised as the symptom of a degenerate society, but anyone even noddingly familiar with Greek vases or statues on ancient Hindu temples will know that so-called unnatural sex acts, orgies and all manner of complex liaisons have for millennia past been represented in art for the pleasure and inspiration of the viewer everywhere. The desire to ponder images of love-making is clearly innate in the human – perhaps particularly the male – psyche.

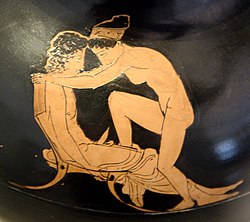

The society of ancient Greece was recognized for its lenient attitudes towards sexual representation in the fields of art and literature.[31] The Greek poet Sappho's Ode to Aphrodite (600 BCE) is considered an earliest example of lesbian poetry.[24] Red-figure pottery invented in Greece (530 BCE) often portrayed images that displayed eroticism.[32] The fifth-century BC comic Aristophanes elaborated 106 ways of describing the male genitalia and in 91 ways of describing the female genitalia.[31] Lysistrata (411 BCE) is a sex-war comedy play that was performed in ancient Greece.[33]

Some ancient Hindu temples incorporated various aspects of sexuality into their art. The temples at Khajuraho and Konark are particularly renowned for their sculptures, which have detailed human sexual activity.[34] These depictions were meant to be seen with a spiritual outlook as sexual arousal was believed to denote the embodying of the divine.[e]

In India, Hinduism embraced an inquisitive attitude towards sex as an art, science and spiritual practice.[37] Kama, the word used to connote sexual desire, was explored in the Indian literary works such as the Kama Sutra and Kamashastra. These collections of sexually explicit writings covered practical, as well as the psychological aspects of human courtship and sexual intercourse.[38][39] The Sanskrit text Kama sutra was put together by the sage Vatsyayana in its final form sometime during the second half of the third century CE.[40] The text included prose, poetry, as well as illustrations regarding erotic love and sexual behaviour,[24] and is one of the most celebrated Indian erotic works.[41] Another medieval Indian literary work that explored sexuality is the Koka shastra.[34]

Other examples of early art and literature of sexual nature include: Ars Amatoria (Art of Love), a second-century CE treatise on the art of seduction and sensuality by the ancient Roman poet Ovid;[42] the artifacts of the Moche people in Peru (100 CE to 800 CE);[24] The Decameron, a collection of short stories some of which are sexual in nature by the 14th-century Italian author Giovanni Boccaccio;[42] and the fifteenth-century Arabic sex manual The Perfumed Garden.[24]

Pornography in early modern era

[edit]A highly developed culture of visual erotica flourished in Japan during the early modern era. From at least the 17th century, erotic materials were part of the mainstream social culture with depictions of sexual intercourse present in pictures that were meant to provide sex education for medical professionals, courtesans, and married couples. Makura-e (pillow pictures) were made for entertainment as well as for guidance of married couples.[42] The ninth-century Japanese art form called "Shunga" that depicted sexual acts on woodblock prints and paintings became so popular by the 18th century that the Japanese government began to issue official edicts against it. Even so, Japanese erotica flourished, with the works of artists such as Suzuki Harunobu achieving worldwide recognition.[24][42]

In Europe, the development of printing press led to the publication of written and visual material which was essentially pornographic. Heptaméron written in French by Marguerite de Navarre and published posthumously in 1558 is one of the earliest example of salacious work from that period. Starting with the age of enlightenment (18th century) along with the advances in printing technology, the production of erotic material became popular enough that an underground marketplace for such works developed in England with a separate publishing and bookselling business.[42] The book Fanny Hill (1748) considered "the first original English prose pornography, and the first pornography to use the form of the novel,"[5] was an erotic literary work by John Cleland, first published in England as Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure.[43][44] The novel has been one of the most prosecuted and banned books in history.[45][46] The author was charged for "corrupting the King's subjects."[47]

At around the same time, erotic graphic art that began to be extensively produced in Paris came to be known in the Anglosphere as "French postcards".[42] Apart from its sexual component, pornography became a medium for protest against the social and political norms of the time. It was used to explore the ideas of sexual freedom for women along with men, the various methods of contraception, and to expose the offences of powerful royals and elites.[42] One of the most important authors of socially radical pornography was the French aristocrat Marquis de Sade (1740–1814), whose name helped derive the words "sadism" and "sadist". He advocated libertine sexuality and published writings that were critical of authorities, many of which contained pornographic content.[48] His work Justine (1791) interlaced orgiastic scenes along with extensive debates on the ills of property and traditional hierarchy in society.[42]

When large-scale archaeological excavations of Pompeii were undertaken in the 18th century, much of the erotic art in Pompeii and Herculaneum came to light, shocking the authorities who endeavored to hide them away from the general public. In 1821, the moveable objects were locked away in the Secret Museum in Naples and what could not be removed was either covered or cordoned off.[50]

During the Victorian era (1837–1901) the invention of the rotary printing press made publication of books easier, many works of lascivious nature were published during this period, often under pen names or anonymity.[51] In 1837, the Holywell Street (known as “Booksellers’ Row”) in London had more than 50 shops that sold pornographic material.[42] Many of the Works published in the Victorian era are considered bold and graphic even by today's lenient standards. Some of the popular publications from this era include: The Pearl (magazine of erotic tales and poems published from 1879 to 1881); Gamiani, or Two Nights of Excess (1870) by Alfred de Musset; and Venus in Furs (1870) by Leopold von Sacher-Masoch, from whose name the term "masochism" was derived.[51] The Sins of the Cities of the Plain (1881) is one of the first sole male homosexual literary work published in English, this work is said to have inspired another gay literary work Teleny, or The Reverse of the Medal (1893), whose authorship has often been attributed to Oscar Wilde.[52] The Romance of Lust, written anonymously and published in four volumes during 1873–1876, contained graphical descriptions of themes detailing incest, homosexuality, and orgies.[53] Other publications from the Victorian era that included fetish and taboo themes like sadomasochism and 'cross-generational sex' are: My Secret Life (1888–1894) and Forbidden Fruit (1898). On accusations of obscenity many of these works had been outlawed until the 1960s.[53]

Criminalization

[edit]The world's first law that criminalized pornography was the English Obscene Publications Act 1857, which was enacted at the urging of the Society for the Suppression of Vice.[54][53] The Act, passed by the British Parliament in 1857 applied to the United Kingdom and Ireland, made the sale of obscene material a statutory offence, and gave authorities the power to seize and destroy any offending material.[55]

When pornographic material flourished in Victorian-era England, the affluent classes believed they are sensible enough to deal with it, unlike the lower working classes whom they thought would get distracted by such material and cease to be productive. Beliefs that masturbation would make people ill, insane, or become blind also flourished.[53] The obscenity act gave government officials the power to interfere in the private lives of people unlike any other law before.[55] Some of the people suspected for masturbation were forced to wear chastity devices. "Cures" and "treatment" for masturbation involved such measures like giving electric shock and applying carbolic acid to the clitoris.[53] The law was criticised for being established on still yet unproven claims that sexual material is noxius for people or public health.[55]

The American equivalent of the Obscene Act was the Comstock Act of 1873.[56][57] The anti-obscenity bill, drafted by Anthony Comstock, was debated for less than an hour in the US Congress before being passed into law. Apart from the power to seize and destroy any material alleged to be obscene, the law made it possible for the authorities to make arrests over any perceived act of obscenity, including possession of contraceptives by married couples. Reportedly in the US 15 tonnes of books and 4 million pictures were destroyed and about 15 people were driven to suicide with 4,000 arrests.[58]

The English Act did not apply to Scotland where the common law continued to apply. Before the English Act the publication of obscene material was treated as a common law misdemeanour,[59] which made effectively prosecuting authors and publishers difficult even in cases where the material was clearly intended as pornography.[60] However, neither the English, nor the United States Act defined what constituted "obscene," leaving this for the courts to determine.[59] For implementing the Comstock act, the US courts used the British Hicklin test to define obscenity, the definition of which became cemented in 1896 and continued until the mid-twentieth century. Starting from 1957 to 1997, the US Supreme Court made numerous judgements that redefined obscenity.[58]

The nineteenth-century legislation eventually outlawed the publication, retail and trafficking of certain writings and images that were deemed pornographic. Although laws ordered the destruction of shop and warehouse stock meant for sale, the private possession and viewing of (some forms of) pornography was not made an offence until the twentieth century.[60] Historians have explored the role of pornography in social history and the history of morality.[61] The Victorian attitude that pornography was only for a select few can be seen in the wording of the Hicklin test stemming from a court case in 1868, where it asked: "whether the tendency of the matter charged as obscenity is to deprave and corrupt those whose minds are open to such immoral influences."[62]

Even though officially prohibited, the sale of sexual material nevertheless continued through "under the counter" means. Magazines specialising in a genre called "saucy and spicy" became popular during this time. Titles of few popular magazines from this period, around 1896 to 1955, are Wink: A Whirl of Girls, Flirt: A FRESH Magazine, and Snappy. Cover stories of these magazines featured segments such as "perky pin-ups" and "high-heel cuties."[63] Some of the popular erotic literary works from the twentieth century include the novels: Story of the Eye (1928), Tropic of Cancer (1934), Tropic of Capricorn (1938), the French Histoire d'O (Story of O) (1954); and short stories: Delta of Venus (1977), and Little Birds (1979).[64]

After the invention of photography, the birth of erotic photography followed. The oldest surviving image of a pornographic photo is dated back to about 1846, described as to depict "a rather solemn man gingerly inserting his penis into the vagina of an equally solemn and middle-aged woman."[63] The Parisian demimonde included Napoleon III's minister, Charles de Morny, an early patron who delighted in acquiring and displaying erotic photos at large gatherings.[65]

Pornographic film production commenced almost immediately after the invention of the motion picture in 1895. A pioneer of the motion picture camera, Thomas Edison, released various films, including The Kiss that were denounced as obscene in late 19th century America.[66][67] Two of the earliest pioneers of pornographic films were Eugène Pirou and Albert Kirchner. Kirchner directed the earliest surviving pornographic film for Pirou under the trade name "Léar". The 1896 film, Le Coucher de la Mariée, showed Louise Willy performing a striptease. Pirou's film inspired a genre of risqué French films that showed women disrobing, and other filmmakers realised profits could be made from such films.[68][69]

Legalization

[edit]Sexually explicit films opened producers and distributors to prosecution. Such films were produced illicitly by amateurs, starting in the 1920s, primarily in France and the United States. Processing the film was risky as was their distribution which was strictly private.[70][71] In 1969, Denmark became the first country to abolish censorship thereby legalizing pornography,[72] including child pornography, which led to an explosion of investment in, and commercial production of pornography. In 1980, Denmark prohibited Child pornography.[73][74] Although legalized in Denmark, pornography was still illegal in other countries and had to be smuggled in where it was then sold "under the counter", or (sometimes) shown in "members only" cinema clubs.[70]

Nonetheless, and also in 1969, Blue Movie by Andy Warhol became the first feature film to depict explicit sexual intercourse that received a wide theatrical release in the United States.[75][76][77]

Blue Movie was real. But it wasn't done as pornography—it was done as an exercise, an experiment. But I really do think movies should arouse you, should get you excited about people, should be prurient. Prurience is part of the machine. It keeps you happy. It keeps you running."

Film scholar Linda Williams remarked that prurience "is a key term in any discussion of moving-image sex since the sixties. Often it is the "interest" to which no one wants to own up."[79] Blue Movie was a seminal film in the Golden Age of Porn and, according to Warhol, a major influence in the making of Last Tango in Paris, an internationally controversial erotica drama film starring Marlon Brando that was released a few years after Blue Movie was made.[76]

In 1970, the United States President's Commission on Obscenity and Pornography, set up to study the effects of pornography, found that there was "no evidence to date that exposure to explicit sexual materials plays a significant role in the causation of delinquent or criminal behavior among youths or adults."[80] The report further recommended against placing any restriction on the access of pornography by adults and suggested that legislation "should not seek to interfere with the right of adults who wish to do so to read, obtain, or view explicit sexual materials."[81] Regarding the notion that sexually explicit content is improper, the Commission found it "inappropriate to adjust the level of adult communication to that considered suitable for children." The Supreme Court supported this view.[81]

In 1979, the British Committee on Obscenity and Film Censorship better known as the Williams Committee, formed to review the laws concerning obscenity reported that pornography could not be harmful and to think anything else is to see pornography "out of proportion". The committee declared that existing variety of laws in the field should be scrapped and so long as it is prohibited from children, adults should be free to consume pornography as they see fit.[82][83]

The Meese Report in 1986, argued against loosening restrictions on pornography in the US. The report was criticized as biased, inaccurate, and not credible.

Pornographic films appeared throughout the twentieth century. First as stag films (1900–1940s), then as porn loops or short films for peep shows (1960s), followed by as feature films for theatrical release in adult movie theaters (1970s), and as home videos (1980s).[84] In 1988, the Supreme Court of California ruled in the People v. Freeman case that "filming sexual activity for sale" does not amount to procuring or prostitution and shall be given protection under the first amendment.[85] This ruling effectively legalized the production of X-rated adult content in the Los Angeles county, which by 2005 had emerged as the largest centre in the world for the production of pornographic films.[85][86]

Pornographic magazines published during the mid-twentieth century have been noted for playing an important role in the sexual revolution,[87] and the liberalization of laws and attitudes towards sexual representation in the Western world.[88] Hugh Hefner, in 1953, published the first US issue of the Playboy, a magazine which as Hefner described is a "handbook for the urban male". The magazine contained images of nude women along with articles and interviews covering politics and culture.[64] Twelve years later, in 1965, Bob Guccione in the UK started his publication Penthouse, and published its first American issue in 1969 as a direct competitor to Playboy. In its early days the images of naked women in Playboy did not show any pubic hair or genitals, Penthouse became the first magazine to show pubic hair in 1970. Playboy followed the lead and there ensued a competition between the two magazines over publication of racy pictures, a contest that got labelled as the "Pubic wars".[88]

"We were the first to show full frontal nudity. The first to expose the clitoris completely. I think we made a very serious contribution to the liberalization of laws and attitudes. HBO would not have gone as far as it does if it wasn't for us breaking the barriers. Much that has happened now in the Western world with respect to sexual advances is directly due to steps that we took." — Bob Guccione, Penthouse founder in 2004.[88]

The tussle between Playboy and Penthouse paled into obscurity when Larry Flynt started Hustler, which became the first magazine to publish labial "pink shots" in 1974. Hustler projected itself as the magazine for the working classes as opposed to the urban centered Playboy and Penthouse.[89] During the same time in 1972, Helen Gurley Brown, editor of the Cosmopolitan magazine, published a centerfold that featured actor Burt Reynolds in nude. His popular pose has been later emulated by many other famous people. The success of Cosmo led to the launch of Playgirl in 1973.[89] In the 2010s, as the market for printed versions of the pornographic magazines declined, many magazines developed their own websites and became online publications.[90] The best-selling US adult magazines maintain greater reach compared to most other non-pornographic magazines, and are amongst the top-sellers.[91]

Modern-day pornography

[edit]Since the 1990s, the Internet has made pornography more accessible and culturally visible.[92] Before the 90s, Usenet newsgroups served as the base for what has been called the "amateur revolution" where non-professionals from the late 1980s and early 1990s, with the help of digital cameras and the internet, created and distributed their own pornographic content independent of the mainstream networks.[93]

The use of the World Wide Web became popular with the introduction of Netscape navigator in 1994. This development paved the way for newer methods of pornography distribution and consumption.[94] The notion that internet is a medium to access pornography became popular enough that in 1995 Time published a cover story titled "Cyberporn".[95]

Danni's Hard Drive started in 1995, by Danni Ashe is considered to be one of the earliest online pornographic websites; coded by Ashe, a former stripper and nude model, the website was reported by CNN in 2000 to have made revenues of $6.5 million.[96][94] In 2012, the total number of pornographic websites were estimated to be around 25 million, comprising 12% of all the websites.[96]

With the introduction of broadband connections, much of the distribution networks moved online, giving consumers anonymous access to a wide range of pornographic material.[92] The development of streaming sites, peer-to-peer file sharing (P2P) networks, and tube sites led to a subsequent decline in the sale of DVDs and adult magazines.[92] Data from 2015 suggests an increase in pornography viewing over the past few decades and has been attributed to the growth of Internet pornography.[97]

Through the 2010s, many pornographic production companies and top pornographic websites[98] such as Pornhub, RedTube and YouPorn have been acquired by MindGeek, a company that has been described as "a monopoly" in the pornography business.[99] As of 2022, the total pornographic content accessible online is estimated to be over 10,000 terabytes.[100] Xvideos.com and Pornhub.com are the two most visited pornographic websites.[101]

Technological advancements such as laptops, digital cameras, smartphones, and Wi-Fi have democratized the production and accessibility of pornography in the modern world.[102][93] Subscription-based service providers such as OnlyFans, founded in 2016, are increasingly becoming popular as the platforms for pornography distribution in the digital era.[103][104] Apart from professional pornographers, content creators on such platforms include others:[103] from a physics teacher,[105] to a race car driver, to a woman undergoing cancer treatment.[106]

XBIZ and AVN are the two industry-specific organizations based in the US that provide legal news and information about the adult entertainment industry.[107] They also present the award shows, XBIZ Awards and AVN Awards. The scholarly study of pornography notably in cultural studies is limited. Porn Studies, started publishing in 2014, is the first peer-reviewed academic journal about the study of pornography.[108] Greater access to the internet and affordable smartphones among people made pornography more culturally mainstream in the twenty-first century.[109]

Classification and commercialism

[edit]Classification

[edit]Pornography is generally classified as either softcore or hardcore based on its content. Nudity is regularly included in both the forms. Softcore pornography contains nudity or partial nudity in a sexually suggestive way but without any explicit depiction of sexual activity,[110] whereas hardcore pornography includes depiction of explicit sexual activity.[111] Softcore pornography is often considered erotica.[112] The distinctness between erotica and pornography is mostly subjective.[42]

Based on the production methods and the intended consumers, pornography is classified as either mainstream or indie.[113] Mainstream pornography mostly caters to the hetrosexual consumers and involves performers working under corporate film studios for their respective productions.[114] Pornography featuring heterosexual acts comprise the bulk of the mainstream porn, marking the industry more or less as "heteronormative."[115]

Indie or independent pornography refers to pornography productions by performers who work independent of mainstream studios. These productions often feature different scenarios and sexual activity compared to the mainstream porn, and cater to a more specific audience.[116][115] The performers in indie porn sometimes work in partnership with other performers. Apart from content creation they do the background work such as videography, editing, and web development themselves and distribute under their own brand.[116] The rise of indie porn has been noted as a cause for decline in the business of mainstream porn. Reportedly, applications for porn-shoot permits by established pornography companies fell by 95 percent during the years 2012-2015.[117]

Pornography encompasses a wide variety of genres, providing for an enormous range of consumer tastes.[115] Some examples of the pornography genres include: alt, bondage, bisexual, convent, ethnic, gonzo, gay, mormon, parody, reality, rape, transgender, zombie etc. The most searched for pornography genres on the internet are: lesbian, hentai, fauxcest, milf, big ass, and creampie.[118] Pornography also features numerous fetishes like: "'fat' porn, amateur porn, disabled porn, porn produced by women, queer porn, BDSM and body modification."[f]

Commercialism

[edit]The production and distribution of pornography are economic activities of some importance. In the United States, the pornography industry employs about 20,000 people, including 2000 to 3000 performers, and is centered in the San Fernando Valley of Los Angeles. By 2005, it had become the largest pornography production centre in the world.[119][85][86] Apart from regular media coverage, the industry receives considerable attention from private organizations, government agencies, and political organizations.[120]

In Europe, Budapest is regarded as the industry center.[121][122][123] Other pornography production centres in the world are located in Florida (US), Brazil, Czech Republic and Japan.[86] Piracy, the illegal copying and distribution of material, is of great concern to the porn industry.[124] The industry is the subject of many litigations and formalized anti-piracy efforts.[125][126]

| Commercialization of pornography | |||

| |||

Revenues of the adult industry in the United States are difficult to determine. In 1970, a federal study estimated the total retail value of hardcore pornography in the United States was no more than $10 million.[81] In 1998, Forrester Research published a report on the online "adult content" industry, estimating annual revenue at $750 million to $1 billion. Studies in 2001 put the total (including video, pay-per-view, Internet and magazines) between $2.6 billion and $3.9 billion.[127] The introduction of home video and the World Wide Web in the late twentieth century led to a global growth in the business of pornography.[128]

In 2010, CNBC has estimated that pornography was a $13 billion industry in the US, with $3,075 being spent on porn every second and a new porn video being produced every 39 minutes.[129] As of 2011, pornography was becoming one of the biggest businesses in the United States.[130] In 2014, the porn industry was believed to bring in more than $13 billion on a yearly basis in the United States.[131]

The exact economic size of the porn industry in the early-twenty-first century is unknown to anyone.[96] Kassia Wosick, a sociologist from New Mexico State University, estimated the global porn market value at $97 billion in 2015, with the US revenue estimated at $10 and $12 billion. IBISWorld, a leading researcher of various markets and industries, calculated total US revenue to reach $3.3 billion by 2020.[96][132] In 2018, pornography in Japan was estimated to be worth over $20 billion.[133]

Technology

[edit]Template:See also Pornographers have taken advantage of each major technological advancement in the production and distribution of their services.[134] Pornography has been called an "erotic engine" and a driving force in the development of various media technologies from the printing press, through photography (still and motion), to satellite TV, from home video, to internet Streaming.[135]

The porn industry has been noted for its influence on the development and popularization of various communication and media processing technologies by being an early adopter of innovations.[136][137] From smaller film cameras, VCR's, to the internet, the porn industry has employed newer technologies much before than other commercial industries, thus aiding in their development by providing the early financial capital.[138][139]

One of the world's leading anti-pornography campaigners, Gail Dines, has stated that "the demand for porn has driven the development of core cross-platform technologies for data compression, search, transmission and micro-payments." Many of the technological developments that have been led by pornography have benefited other fields of human activitiy too.[30]

The way you know if your technology is good and solid is if it's doing well in the porn world.

In the early 2000s, Wicked Pictures pushed for the adoption of the MPEG-4 file format ahead of others, this later became the most commonly used format across high-speed internet connections.[141] In 2009, Pink Visual became one of the first companies to license and produce content with a software introduced by a small toronto-based company called "Spatial view" that later made it possible to view 3-D content on iphones.[136]

Many of the innovative data rendering procedures, enhanced payment systems, customer service models, and security methods developed by pornography companies have been co-opted by other mainstream businesses.[142][7] Pornography companies served as the basis for a large number of innovations in web development. Much of the IT work in porn companies is done by people who are referred to as a "porn webmaster", often paid well in what are small businesses, they have more freedom to test innovations compared to other IT employees in larger organizations who tend to be risk-averse.[143]

The pornography industry has been considered an influential factor in deciding the format wars in media, including being a factor in the VHS vs. Betamax format war (the videotape format war)[144][145] and the Blu-ray vs. HD DVD format war (the high-def format war).[144][145][146] The success of innovative technologies is predicted by their greater use in the porn industry.[147]

The various mediums for pornography depictions have evolved throughout the course of human history; starting from prehistoric cave paintings, about forty millennia ago, to futuristic virtual reality renditions.[148][149][7] Some pornography is produced without human actors at all. The idea of completely computer-generated pornography was conceived very early as one of the obvious areas of application for computer graphics and 3D rendering. Until the late 1990s, digitally manipulated pornography could not be produced cost-effectively. In the early 2000s, it became a growing segment as the modelling and animation software matured, and the rendering capabilities of computers improved. Further advances in technology have allowed increasingly photorealistic 3D figures to be used in interactive pornography.[150][151][152] The first pornographic film to be shot in 3D was 3D Sex and Zen: Extreme Ecstasy, released on 14 April 2011, in Hong Kong.[153]

Consumption

[edit]Pornography is a product made by adults for adult consumers.[154] The vast majority of US men use porn.[g][156] The Huffington Post reported in 2013 that 70% of men and 30% of women watch porn, with porn websites registering higher number of visitors than Netflix, Amazon, and Twitter combined.[157][158] A study in 2008 found that among University students aged 18 to 26, located in six college sites across the United States; 67% of young men and 49% of young women approved pornography viewing, with nearly 9 out of 10 men (87%) and 31% women reportedly using pornography.[159]

About 90% of pornography is consumed on the internet with consumers preferring content that's in tune with their sexuality.[160][161] Researchers at McGill University ascertained that on viewing pornographic content, men reached their maximum arousal in about 11 minutes and women in about 12 minutes.[162] An average visit to a pornographic website lasts for 11.6 minutes.[163] Both marriage and divorce are found to be associated with lower subscription rates for adult entertainment websites.[164] Subscriptions are more widespread in regions that have higher measures of social capital.[165] Pornographic websites are often visited during office hours.[166] No correlation has been found between the practice of sexual consent or lack thereof and pornography consumption in people.[167]

A 2006 study of Norwegian adults found that over 80% of the respondents used pornography at some point in their lives. A difference of 20% between men and women was observed in their respective use. Since the late 1960s, attitudes towards pornography have become more positive in Nordic countries, in Sweden and Finland the consumption of pornography has increased over the years.[168] In 2022, a national survey in Japan, of men and women aged 20 to 69 revealed that 76% of men and 29% of women used pornography as part of their sexual activity.[169]

Legality and regulations

[edit]Template:Sex and the Law The legal status of pornography varies widely from country to country.[170][171] Regulating hardcore pornography is more common than regulating softcore pornography.[172] Child pornography is illegal in almost all countries,[173][174] some countries have restrictions on rape pornography and animal pornography.[174]

In the United States, a person receiving unwanted commercial mail that he or she deems pornographic (or otherwise offensive) may obtain a Prohibitory Order.[175] Disseminating pornography to a minor is generally illegal.[174] Many online sites require the user to tell the website they are a certain age and no other age verification is required.[176] The Child Online Protection Act would have restricted access by minors to any material on the Internet that is considered harmful to them, but it did not take effect.[176] There are various measures to restrict minors' any access to pornography,[174][176] including protocols for pornographic stores.[174]

The adult film industry regulations in California require that all actors and actresses practice safe sex using condoms. It is rare to see condom use in pornography.[177] As porn does better financially when actors are without condoms, many companies film in other states. Miami is a major area for amateur porn.[178] Twitter is the popular social media platform used by the performers in porn industry as it does not censor content unlike Instagram and Facebook.[178][179]

Pornography can infringe into basic human rights of those involved, especially when sexual consent was not obtained. For example, revenge porn is a phenomenon where disgruntled sexual partners release images or video footage of intimate sexual activity, usually on the internet, without authorization from the other person.[180] Lawmakers have also raised concerns about "upskirt" photos taken of women without their consent. In many countries there has been a demand to make such activities specifically illegal carrying higher punishments than mere breach of privacy, or image rights, or circulation of prurient material.[181][182] As a result, some jurisdictions have enacted specific laws against "revenge porn".[183] The UK government has criminalized possession of what it terms "extreme pornography," following the highly publicized murder of Jane Longhurst.

What is not pornography

[edit]In the US, a July 2014 criminal case decision in Massachusetts; Commonwealth v. Rex, 469 Mass. 36 (2014),[184] made a legal determination of what was not to be considered "pornography" and in this particular case "child pornography".[185] It was determined that photographs of naked children that were from sources such as National Geographic magazine, a sociology textbook, and a nudist catalog were not considered pornography in Massachusetts even while in the possession of a convicted and (at the time) incarcerated sex offender.[185]

Drawing the line depends on time, place and context; Occidental mainstream culture has been increasingly getting "pornified" (i.e. influenced by pornographic themes, and mainstream films often include unsimulated sexual acts).[186] As the very definition of pornography is subjective, material that is considered erotic or even religious in one society may be denounced as pornography in another. Thus, Europeans who visited India in the 19th century were appalled by the religious representation of sexuality on the Hindu temples and considered them as pornographic. Similarly many films and television programs that are unobjectionable in contemporary Western societies are labelled as "pornography" in Muslim societies. As an adaptation of a popular cliché, "pornography is very much in the eye of the beholder."[42]

Copyright status

[edit]In the United States, some courts have applied US copyright protection to pornographic materials.[187][188] Some courts have held that copyright protection effectively applies to works, whether they are obscene or not,[189] but not all courts have ruled the same way.[190] The copyright protection rights of pornography in the United States has again been challenged as late as February 2012.[187][191]

STIs prevention and safer sex practices

[edit]Template:See also Performers working in pornographic film studios undergo regular testing for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) every two weeks.[192] They have to test negative for: HIV, trichomoniasis, chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, and hepatitis B and C before showing up on a set who are then inspected for sores on their mouths, hands, and genitals before commencing work. The industry believes this method of testing to be a viable practice for safer sex as its medical consultants claim that since 2004, about 350,000 pornographic scenes have been filmed without condoms and HIV has not been transmitted even once because of performance on set.[193][194] However, some studies suggest that adult film performers have high rates of chlamydia and/or gonorrhea infection, and many of these cases may be missed by industry screening because these bacteria can colonize many sites on the body.[85][86]

Allan Ronald, a Canadian doctor and HIV/AIDS specialist who did groundbreaking studies on the transmission of STIs among prostitutes in Africa, said there's no doubt about the efficiency of the testing method, but he felt a little uncomfortable: "because it's giving the wrong message — that you can have multiple sex partners without condoms — but I can't say it doesn't work."[193][194]

Relatedly, it has been found that individuals who have received little sex education and/or perceive pornography as a source of information about sex are less apt to use condoms.[195][196] The Free Speech Coalition cautions viewers to not consider pornography as sex education material and to not enact what they see as porn presents an unrealistic image of sexuality, much as tobacco ads present an ideal image of people smoking without showing its ill effects.[197] In 2020, the US National Sex Education Standards, released recommendations to incorporate porn literacy to students from grade 6 to 12 as part of sex education in the United States.[198]

Pornographic actress Nina Hartley, who has a degree in nursing, stated that the amount of time involved in shooting a scene can be very long, and with condoms in place it becomes a painful proposition as their usage is uncomfortable despite the use of lube, causes friction burn, and opens up lesions in the genital mucosa. Advocating the testing method for performers in the industry, Hartley said, "Testing works for us, and condoms work for outsiders."[193][199]

Emphasizing that performers in the industry take necessary precautions like PrEP and are at lower risk to contract HIV than most sexually active persons outside the industry,[194] many prominent female performers have vehemently opposed regulatory measures like Measure B that sought to make the use of condoms mandatory in pornographic films. Professional female performers have called the use of condoms on a daily basis at work an occupational hazard as they cause micro-tears, friction burn, swelling, and yeast infections, which altogether, they say, makes them more susceptible to contract STIs.[h]

Views on pornography

[edit]General

[edit]Pornography has been notable for serving as a safe outlet to sexual desires that may not be satisfied within relationships and for being a facilitator of sexual release in people who cannot or do not want to have real partners.[137] Pornography is viewed by people in general for various reasons; varying from a need to enrich their sexual arousal, to facilitate orgasm, as an aid for masturbation, learn about sexual techniques, reduce stress, alleviate boredom, enjoy themselves, see representation of people like themselves, know their sexual orientation, improve their romantic relationships, or simply because their partner wants them to. Research has suggested presence of four broad motivations in people for using pornography, namely: "using pornography for fantasy, habitual use, mood management, and as part of a relationship."[101] Men are found to consume pornography more frequently than women, with the intent for consumption that may vary with men more likely to use pornography as a stimulant for sexual arousal during solitary sexual activity, while women are more likely to use pornography as a source of information or entertainment, and rather prefer using it together with a partner to enhance sexual stimulation during partnered sexual activity.[1][100]

Studies have found that sexual functioning defined as "a person's ability to respond sexually or to experience sexual pleasure" is greater in women who frequently consume pornography than in women who do not. No such association has been found in men though.[1] Women who consume pornography are more likely to know about their own sexual interests and desires, and in turn be willing and able to communicate them during partnered sexual activity; it has been reported that in women the ability to communicate sexual preferences is associated with greater sexual satisfaction. Pornographic material is found to expand the sexual repertoire in women by making them learn new rewarding sexual behaviours such as clitoral stimulation and enhance their overall 'sexual flexibility'. Women who consume pornography frequently are more easily aroused during partnered sex and are more likely to engage in oral sexual activity compared to the women who do not view pornography.[1] Women users of pornography had reported (almost 50%) to have engaged in cunnilingus, which research suggests is related to female orgasm, and to have had experienced orgasms more frequently than women who do not use pornography (87% vs. 64%).[101]

A two year long survey (2018-2020) conducted to assess the role of pornography in the lives of highly educated medical university students, with median age of 24, in Germany found that pornography served as an inspiration for many students in their sex life.[100] Pornography use among students was higher in males than in females, among the male students those who did not cheat on their partner or contracted an STI were found to be more frequent consumers of pornography. Although pornography use was more common among men, associations between pornography use and sexuality were more apparent in women. Among the female students, those who reported to be satisfied with their physical appearance have consumed three times as much pornography than the female students who had reported to be dissatisfied with their body. A feeling of physical inadequacy was found to be a restraining factor in the consumption of pornography. Female students who consume pornography more often had reported to have had multiple sexual partners. Both female and male students who enjoyed the experience of anal intercourse in their life have been reported to be frequent consumers of pornography. Sexual content depicting bondage, domination, or violence was consumed by only a minority of 10%. More sexual openness and less sexual anxiety was observed in students who regularly consumed pornography. No association has been found between regular pornography use and experience of sexual dissatisfaction in either female or male students. This finding was in concurrence with another finding from a longitudinal study, which demonstrated that most consumers of pornography differentiate pornographic sex from real partnered sex and do not experience diminishing satisfaction with their own sex life.[100]

Pornography is often equated with Journalism as both offer a view of the unknown or hidden aspects of people in a society. French philosopher Michel Foucault remarked that, "it is in pornography that we find information about the hidden, the forbidden and the taboo."[203] Pornography has been referred by people as a means to explore their own sexuality. People have reported porn being helpful in learning about human sexuality in general. Studies have encouraged clinical practitioners to use pornography as an instruction material to show clients new and alternative sexual behaviours as part of their psychosexual therapy.[1] British psychologist, Oliver James, known for his work on 'happiness', stated that "a high proportion of men use porn as a distraction or to reduce stress … It serves an anti-depressant purpose for the unhappy."[204] Surveys have found a gradual increase in acceptance of pornography over the years among the general American public.[205]

Feminist

[edit]Feminist movements in the late 1970s and 1980s dealt with the issues of pornography and sexuality in debates that are referred to as the "sex wars".[206] While some feminist groups sought to abolish pornography believing it to be harmful, other feminist groups have opposed censorship efforts insisting it is benign.[2]

A large scale study of data from the General Social Survey (2010–2018) refuted the argument that pornography is inherently anti-woman or anti-feminist and that it drives sexism. The study did not find a relationship between "pornography viewing" and "pornography tolerance" with higher sexism—a posit that was held by some feminists; it instead found them to be associated with greater support for gender equality. The study concluded that "pornography is more likely to be about the sex rather than the sexism."[2] People who supported regulated pornography expressed lesser attitudes of sexism than people who sought to abolish pornography. Notably, non-feminists are found more likely to support a ban on pornography than feminists. Many feminists, both male and female, have reflected that the effects of pornography on society are neutral.[2] Users of pornography were found more egalitarian than nonusers; they are more likely to hold favorable attitudes towards women in positions of power and in workplaces outside home than the nonusers.[207]

Black feminist scholars have criticised the American adult entertainment industry for what they perceive as omission and exclusion of non-white women.[208] Mainstream porn studios feature Black women for lesser number of times than white women in their productions.[209] Mireille Miller-Young in her research on porn industry had found that black women make less money then their white counterparts. White women have historically made 75 percent more per scene and sometimes still make 50 percent more compared to the black women.[209] Black feminists have identified the non representation of black women in interracial pornography, which happens to be one of the most financially prosperous genres in contemporary American commercial pornography, and the creation of another category "reverse IR," as reflective of the larger societal ideals of beauty and body that render women of color as "not merely invisible but also inhuman."[208] As pornography becomes a kind of manual on how bodies in pleasure can look, and is "one of the few places where we see our bodies--and other people's bodies," it becomes imperative on pornography to represent "variety of forms," stated the black feminist scholars.[208]

Prominent anti-pornography feminists such as Andrea Dworkin and Catharine MacKinnon argue that all pornography is demeaning to women, or that it contributes to violence against women–both in its production and in its consumption. The production of pornography, they argue, entails the physical, psychological, or economic coercion of the women who perform in it. They charged that pornography eroticizes the domination, humiliation and coercion of women, and reinforces sexual and cultural attitudes that are complicit in rape and sexual harassment.[210][211][212] Other exclusionary feminists have insisted that pornography presents a severely distorted image of sexual consent, and that it reinforces sexual myths like: women are readily available–and desire to engage in sex at any time–with any man–on men's terms–and always respond positively to men's advances.[213]

In contrast to the objections, other feminist scholars "ranging from Betty Friedan and Kate Millett to Karen DeCrow, Wendy Kaminer and Jamaica Kincaid" have supported the right to consume pornography.[214] Wendy McElroy has noted that both feminism and pornography are mutually related, with both thriving in environments of tolerance, and both repressed anytime regulations are placed on sexual expression.[215] Societies where pornography and sexual expression is prohibited are more likely to be the places where women are often subjected to violence and sexual abuse.[216]

Women's rights are far stronger in societies with liberal attitudes to sex – think of conservative countries such as Afghanistan, Yemen or China, and the place of women there. And yet, anti-porn campaigners neglect such issues entirely. A recent study by the US department of justice compared the four states that had highest broadband access and found there was a 27 per cent decrease in rape and attempted rape, and the four with the lowest had a 53 per cent increase over the same period.

The lesbian feminist movement of the 1980s is considered a seminal moment for the women in the porn industry as more women entered into the developmental side of the industry. This allowed women to gear porn more towards women as they knew what women wanted, both from the perspective of actresses as well as the female audience. This change has been considered a good development as for a long time the porn industry has been directed by men for men. This move also sparked the arrival of making lesbian porn for lesbians instead of men.[217]

Furthermore, the advent of Vcr, home video, and affordable consumer video cameras allowed for the possibility of feminist pornography.[218] Consumer video made it possible for the distribution and consumption of video pornography; and to locate women as legitimate consumers of pornography.[219] Feminist porn directors are interested in challenging representations of men and women, as well as providing sexually-empowering imagery that features many kinds of bodies.[220] Tristan Taormino says that feminist porn is "all about creating a fair working environment and empowering everyone involved."[219] Porn for women is identified by factors like greater attention to "sensual surroundings" and "soft focus camerawork," rather than on the explicit depiction of sexual activity, making the productions more warm and humane compared to the traditional porn made for hetrosexual men.[221]

"If feminists define pornography, per se, as the enemy, the result will be to make a lot of women ashamed of their sexual feelings and afraid to be honest about them. And the last thing women need is more sexual shame, guilt, and hypocrisy—this time served up by feminism" — Ellen Willis.[222]

Porn industry has been noted for being one of the few industries where women enjoy a power advantage in the workplace. "Actresses have the power," Alec Metro, one of the men in line, ruefully noticed of the X-rated industry. A former firefighter who claimed to have lost a bid for a job to affirmative action, Metro was already divining that porn might not be the ideal career choice for escaping the forces of what he called 'reverse discrimination.'[223] Female performers can often dictate which male actors they will and will not work with. Porn—at least, porn produced for a heterosexual audience—is one of the few contemporary occupations where the pay gap operates in the favour of women. The average actress makes fifty to a hundred per cent more money than her male counterpart.[223][224]

Religious

[edit]As most religions have long and vehemently opposed sexual natured things in general, religious people are found highly susceptible to experience great distress in their use of pornography. Religious people who use pornography tend to feel sexually ashamed.[225] Sexual shame, which rises from a person's perception of their self in other people's minds, is considered to be a powerful factor that over time governs individual behaviour. As sexuality is interwoven into one's personal identity, sexual shame or embarrassment attack a person's very sense of self.[225]

When a sexual shaming event occurs, the person attributes causation to oneself—resulting in self condemnation—and experience feelings of sadness, loneliness, anger, unworthiness, and rejection along with a perceived judgment of self by others.[225] In this mental landscape, a fear arises that ones sexual self needs to be hiden. This psychological process initiates and fuels further shame and lowers one's self-esteem. Sexual shame in people begets more shame and leads to a cycle of powerlessness, culminating in deepening negative emotions.[225]

People who tend to feel shame easily are found to be at greater risk for depression and anxiety disorders; the cause of attributing shame to sexuality is traced back to the biblical interpretation of nakedness being shameful.[226] Much of the Christian mythology presented sexuality as an obstacle to be surmounted in the way of salvation. The major abrahamic religions condemn and consider all forms of nonmarital and nonreproductive sexual pleasure as unacceptable. Whereas in Hinduism, bhoga (sexual pleasure) is celebrated as a value in itself and is considered one of the two ways to nirvana, the alternative being the more demanding yoga.[i] One of the central concepts in Hinduism is that of Purushartha, which is defined as the objective or purpose of human existence. It essentially advocates pursuit of the four main proper goals for a happy life, namely: Dharma (virtuous living, performance of ones duty), Artha (acquiring money, wealth), Kama (sensual delight, sensory pleasures) and Moksha (spiritual knowledge, self-actualization).[228] The pursuit of Kama was elaborated by the sage Vatsyayana in his treatise Kama Sutra, wherein he opined that sexual pleasure is essential for the well being of the body just as food, and that on both of them are founded virtue and prosperity. Food, despite causing indigestion sometimes, would still be consumed regularly, and so it must be with pleasure, which must be pursued with caution while eliminating any unwanted or harmful effects. Just as no one abstains from cooking food worrying that a beggar may come and ask for it, or restrain from sowing wheat fearing animals, similarly claims Vatsyayana, one must pursue kama even though dangers exist; and the man accomplished in Dharma, Artha, and Kama would attain happiness in this world and hereafter.[229]

According to Indonesia's foremost Islamic preacher, Abdullah Gymnastiar, shame is a noble emotion commanded in the Qur'an and was held high by the prophet Muhammad, who had been quoted as saying "Faith is compiled of seventy branches… and shame is one of them." To cultivate shame in the believers, sexual gaze needs to be checked as unchecked gaze is believed to be the door through which Satan enters and soils the believers heart.[230] In 2006 when anti-pornography protests erupted in Indonesia, the world's most populous Muslim-majority country, over the publication of the inaugural Indonesian edition of Playboy; Abdullah called for a legislation to ban pornography and embarked on a mission to shroud the state with a sense of shame, giving the slogan "the more shameful, the more faithful." During these protests, Indonesia's foremost Islamic newspaper, Republika, published daily front page editorials that featured a logo of the word pornografi crossed out with a red X. Playboy's Jakarta office was ransacked by the members of Islamic Defenders Front (Front Pembela Islam or FPI), and bookstore owners were threatened to not sell any issue of the magazine. Eventually in December 2008, Indonesian lawmakers signed an anti-pornography bill into law with overwhelming political support.[230]

Highly religious people are more likely to support policies against pornography such as censorship than least religious people.[231] Religious people are prone to having obsessive thoughts regarding sin and punishment by God over their pornography use causing them to feel ashamed, and perceive themselves to have pornography addiction while also suffering from OCD related symptoms.[232] States that are highly religious and conservative were found to search for more Internet pornography.[233]

Most people, don't likely consider pornography use by a partner as indulging in infidelity.[234] Some Christian denominations consider pornography use among Christian men and women as engaging in "digital adultery."[235] Theological professings on the notion of "digital adultery" speculate about the institution of marriage, and the course of romantic and marital relationships of humans in future with the advent of Sex robots.[236]

Critical

[edit]Template:See also Neuroscience has noted that minds of the young are in developmental stages and exposure to emotionally charged material such as pornography would likely have an impact on them unlike on adults, and has suggested caution while enabling potential access to such material.[237]

The increasing prevalence of alleged beauty enhancing procedures such as breast augmentation, and labiaplasty, among the common populace has been attributed to the popularity of pornography.[238] Studies on the harmful effects of pornography include finding any potential influence of pornography on rape, domestic violence, sexual dysfunction, difficulties with sexual relationships, and child sexual abuse.[239] A longitudinal study has ascertained that pornography use cannot be a perpetrating factor in intimate partner violence.[d][6] Several studies conclude that liberalization of porn in society may be associated with decreased rape and sexual violence rates, while others suggest no effect, or are inconclusive.[240][241][242] Scholars have stated that pornography use could have no implication on public health as pornography use does not meet the definition of a public health crisis.[101] While some literature reviews suggest pornographic images and films can be addictive, insufficient evidence exists to draw conclusions.[243][244][245] Mental health experts are divided over the issue of pornography use being a problem for people.[246] While it has not been proven that either porn or masturbation addiction exist, porn or masturbation compulsion may probably exist.[247][248]

Some issues of doxing and revenge porn have been linked to a few pornography websites.[249][250][251] Deepfake pornography has become an issue of concern for women in general.[150]

See also

[edit]Notes and references

[edit]- ^ Jump up to: a b Pornography can be defined as "material [e.g., pictures, films, videos or text] deemed sexual, given the context, that has the primary intention of sexually arousing the consumer, and is produced and distributed with the consent of all persons involved" (McDonald & Kirkman, 2019, p. 163). Central in the definition of pornography is the consent of all persons involved. Therefore, materials that were produced or distributed without the consent of at least one person involved (e.g., "revenge porn," "child pornography") were excluded from this definition (McDonald & Kirkman, 2019).[1] Pornography is best defined as a medium, such as a picture, video, or text, that is intended to be treated as sexually arousing (Rea, [41]). [...] pornography is framed as an aid for sexual arousal (Parvez, [32]).[2]

- ^ Representative studies indicate that pornography use is a common recreational activity—equivalent with other digitally mediated behaviors (e.g., video games, social media)—with a majority of men and a sizable plurality of women reporting regular use of pornography.[3]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Anthropologist Paul Mellars of Stony Brook University in New York state says the focus on exaggerated sexual features fits with other artifacts found from the period, including phalluses carved out of bison horn and vulva inscribed on rocks. "It's sexually exaggerated to the point of being pornographic," Mellars says. "There's all this sexual symbolism bubbling up in that period. They were sex-mad." Conard used radiocarbon dates from bones and other artifacts found nearby to date the figurine. "It's at least 35,000 calendar years old, but I think it's much older than that," Conard says.[25]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Using a large longitudinal sample of university students (N = 892) over a three-month time lag with two waves and a cross-lagged panel design, we found that pornography use does not prospectively predict the perpetration of intimate partner violence, and that the perpetration of intimate partner violence does not prospectively predict pornography use. Further, gender does not moderate these relationships.[6]

- ^ Jump up to: a b For Tantra the greatest energy was sexual and the sexual organs represented cosmic powers, as symbolized in the linga of Shiva. Some yogis worshipped their own linga, with full ritual, and sexual arousal indicated the coming of the divine presence. The snake was naturally a symbol of sexual power, in the kundalini and other concepts. Similarly the female yoni was worshipped, and many sculptures depicted not only the female body but its prominent genitals. Sexual intercourse (maithuna) of any kind was treated in a ritual fashion, between husband and wife, or different partners, or with a temple girl. Sexual union was transformed into a ceremonial through which the human couple became a divine pair. The rite was prepared by meditation and ceremonies to make it fruitful, for bodily union alone was not thought to be sufficient to bring salvation. The act of sex was formal and not promiscuous, and coition was not a quick relief in orgasm but a long process in caresses and different postures, for which the Kama Sutra and other manuals were of great help.[35] BG 7.11: O best of the Bharatas, in strong persons, I am their strength devoid of desire and passion. I am sexual activity not conflicting with virtue or scriptural injunctions.[36]

- ^ The pornographic genre is immense, and includes an enormous variety of styles catering to an equally vast range of tastes and fetishes. Certainly, mainstream heteroporn makes up the main bulk of the genre, and is most easily accessible. As stated above, this style of porn includes highly formulaic displays of paired or group sex, enacted by bodies exhibiting a conventional gendered aesthetic, moving through various sexual positions and penetrations. Nonetheless, some forms of porn are more normative than others, and indeed not all forms of heteroporn are normative, such as 'rimming', girl-on-boy strap-on anal sex, and hard-core BDSM. Pornography also includes an endless array of different kinds of fetish, 'fat' porn, amateur porn, disabled porn, porn produced by women, queer porn, BDSM and body modification. The list of non-mainstream porn is endless and displays bodies, gender scenarios and sexual activity differently to heteronormative formulations of mainstream heteroporn.[115]

- ^ If estimates generated from the RIA or NFSS are more valid, then pornography use is—or perhaps has become—a common and frequent experience among men, with just under half of all men using pornography in an average week. It is also not an uncommon or infrequent occurrence for women, with nearly one in five reporting pornography use in the past week.[155]

- ^ She didn't know that the dangers of it, like if the condom breaks, and that we could get more STI's with the micro-tears, and just the condoms in general: Swelling, yeast infections, things of that nature—she just had no idea.[200] After hours of sex with no breaks, attempting to endure the friction of the condom in your vagina or anus is...impossible. And to do this daily amounts to an occupational work hazard. Of course, due to the lack of respect towards the adult business and blatant disregard from society regarding the sexual comfort or even opinions of female performers, none of this mattered. No one asked us.[201]

- ^ In much of Christian mythology, sex is a barrier to be overcome. Mortality is transcended and salvation achieved by redemption and ascetic denial of the senses, especially one’s sexual impulses. Christian views have generally been very uncomfortable with any form of sensual pleasure, especially erotic and sexual pleasures. In the West, sexual pleasure is disruptive and dangerous to both the individual and society. It is a monster in the groin, which, if unleashed, could drive men to uncontrollable indulgence and destroy society. Work, not play, is redemptive. Sexual pleasure is moral when it leads men and women to undertake the burdens and responsibilities of raising children. In this view, sexual relations are immoral and sinful whenever they are indulged in outside marriage or without an openness to procreation. Thus orthodox Judaism, official Catholicism, and Protestant fundamentalists condemn masturbation and all forms of nonmarital, nonreproductive sex. Also unacceptable are alternate sexual behaviors and relationships—playful/recreational sex, gay unions, pre- and co-marital sex, and intimate friendships. In contrast, Hinduism celebrates sexual pleasure as a value in its own right, to be enjoyed for what it brings the participants. Kama, “the pursuit of love of pleasure, both sensual and aesthetic,” represents one of the four goals of life in the Hindu tradition. In Hindu philosophy, Bhoga (sexual pleasure) is viewed as one of two paths leading to nirvana, the Buddha, and final deliverance. Yoga, spiritual exercise, is the alternate, and more demanding, path to liberation and the merging of the individual with the universal. In the Tantric yoga tradition, a man or woman can even practice channeling his or her sexual energies from the lowest chakra to the highest and achieve cosmic awareness and transcendence in solo sex or masturbation.[227]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Komlenac & Hochleitner 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Speed et al. 2021.

- ^ Grubbs, Floyd & Kraus 2023.

- ^ Hyde 1964, p. 1-26.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Foxon 1965, p. 45.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hatch et al. 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Barss 2010, p. 1.

- ^ McNair 2013, p. 20.

- ^ pornos 2023.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c etymonline 2023.

- ^ Liddell & Scott 1940.

- ^ Gulick 1927.

- ^ McNair 2013, p. 21.

- ^ greek-language.gr.

- ^ etymonline 2022.

- ^ podictionary & 13 March 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Talvacchia 2010.

- ^ OED 1989.

- ^ Mikkola 2019, p. 2-12.

- ^ McElroy 1995, p. 29-35.

- ^ McNair 2013, p. 19.

- ^ Tarrant 2016, p. 3.

- ^ Rudgley 2000, p. 184-200.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Tarrant 2016, p. 11.

- ^ Science & 13 May 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Black & Green 1992, p. 150-152.

- ^ Nemet-Nejat 1998, p. 137.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Robins 1993, p. 189-190.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c O'Connor 2001.

- ^ Jump up to: a b McNair 2013, p. 23.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Smith 2009.

- ^ Pomeroy et al. 1999, p. 110.

- ^ Cartledge 2002, p. 89.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Parrinder 1996, p. 33.

- ^ Parrinder 1996, p. 36-37.

- ^ Gita 2014.

- ^ Parrinder 1996, p. 5-8.

- ^ Castleman 2013.

- ^ Joseph 2015.

- ^ Doniger & Kakar 2002, pp. xi–xii.

- ^ Parrinder 1996, p. 28.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k Jenkins 2023.

- ^ Cleland 2010, p. 7.

- ^ Lane 2000, p. 11.

- ^ Browne 2001, p. 273.

- ^ Sutherland 1983.