Peter Chamberlen

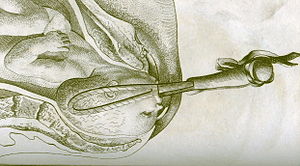

Peter Chamberlen was the name of two brothers, the sons of William Chamberlen (c. 1540 – 1596), a Huguenot surgeon who fled from Paris to England in 1576. They are famous for inventing the modern use of obstetrical forceps. It remained a family secret for over a century.

Peter the Elder

[edit]Peter the Elder lived from 1560 to 1631 and became a surgeon and obstetrician to Queen Anne (Anne of Denmark) in London. One source states that he had no children[1] but other sources suggest he had at least three including Hester, the wife of Thomas Cargill of Aberdeen and several grandchildren. All were mentioned in his will, proved in 1631.[citation needed]

Peter the Younger

[edit]Peter the Younger lived from 1572 to 1626 and also worked as surgeon and obstetrician. He married Sara de Laune, the daughter of a Huguenot, who lived in London. They had eight children, among them Dr. Peter Chamberlen, an obstetrician who carried on the secret use of the forceps. He lived in Woodham Mortimer in Essex, England.

Peter the Elder is believed to be the inventor of the forceps. The brothers went to great length to keep the secret. When they arrived at the home of a woman in labour, two people had to carry a massive box with gilded carvings into the house. The pregnant patient was blindfolded so as not to reveal the secret, all the others had to leave the room. Then the operator went to work. The people outside heard screams, bells, and other strange noises until the cry of the baby indicated another successful delivery.

The secret was kept in the family for another three generations.

The family home, Woodham Mortimer Hall, a 17th century gabled house, has a blue plaque fixed to the hall noting them as pioneering obstetricians. The hall passed out of the Chamberlen family in 1715 when the family home was sold. The forceps were found in 1813 under a trap door in the loft of the hall and given to the Medical and Chirurgical Society which passed them to the Royal Society of Medicine in 1818.[2]

Later Chamberlens

[edit]- Dr. Peter Chamberlen, also Peter the Third, born in 1601 as a son of Peter the Younger, had a good medical education and continued the tradition. He attended the birth of the future King Charles II by Queen Henrietta Maria. His attempt to create a Corporation of Midwives was opposed by the College of Physicians. He was a noted medical doctor, public health advocate, and seventh-day sabbatarian Christian.[3]

He died in 1683.

- His eldest son, Hugh the elder Chamberlen (1630-?1720), also practiced obstetrics using the secret forceps. In 1670, he travelled to France and tried to sell the secret to the French government. François Mauriceau gave him a test,- to deliver a 38 year old dwarf with a grossly malformed pelvis who was in obstructed labor. He failed in this impossible task and returned to England. Hugh Chamberlen later went to the Netherlands and sold his secret to Roger Roonhuysen. The secret was sold further by the Medico-Pharmaceutical College of Amsterdam to selected physicians. After a couple of years somebody made the secret public, but only one blade of the forceps had been revealed. Hugh the Elder eventually moved to Scotland. There, in 1694, he published a book advocating health insurance.

- His son, Hugh the younger Chamberlen (1664-1728), was the last in the Chamberlen family to practice the secret use of the forceps. Toward the end of his life the design and use of the instrument entered the public domain. The first illustration of the forceps was published by Edward Hody in 1734.

References

[edit]- ^ "History of the Chamberlen family by Peter M.Dunn". Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- ^ Christie, Damian (September 2004). "The Surgeon returns to Melbourne; Chamberlen's forceps find a home at the College" (PDF). O&G. 6 (3). Victoria, Australia: The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists: 246–247. Retrieved 16 November 2008.

- ^ Katz, David S. (1988) Sabbath and sectarianism in seventeenth-century England. Leiden, Netherlands. Brill. 224 pages, pp. 48-89

- Williams Obstetrics, 14th edition. Appleton-Century-Crofts, New York, NY, 1971, pages 1116-8.

External links

[edit]- Pages using the JsonConfig extension

- Use dmy dates from September 2011

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from April 2007

- 1560 births

- 1631 deaths

- 1572 births

- 1626 deaths

- 1601 births

- 1683 deaths

- Obstetricians

- French surgeons

- Huguenots

- Articles about multiple people

- 16th-century French people

- 17th-century French people

- 16th-century English people

- 17th-century English people

- People of the Tudor period

- People of the Stuart period