Forty-seven Ronin

The revenge of the Forty-seven Ronin (四十七士 Shi-jū-shichi-shi?), also known as the Forty-seven Samurai, the Akō vendetta, or the Genroku Akō incident (元禄赤穂事件 Genroku akō jiken?) took place in Japan at the start of the 18th century. One noted Japanese scholar described the tale as the country's "national legend."[1] It recounts the most famous case involving the samurai code of honor, bushidō.

The story tells of a group of samurai who were left leaderless (becoming ronin) after their daimyo (feudal lord) Asano Naganori was forced to commit seppuku (ritual suicide) for assaulzzting a court official named Kira Yoshinaka, whose title was Kōzuke no suke. The ronin avenged their master's honor after patiently waiting and planning for two years to kill Kira. In turn, the ronin were themselves forced to commit seppuku for committing the crime of murder. With much embellishment, this true story was popularized in Japanese culture as emblematic of the loyalty, sacrifice, persistence, and honor that all good people should preserve in their daily lives. The popularity of the almost mythical tale was only enhanced by rapid modernization during the Meiji era of Japanese history, when it is suggested many people inSsss Japan longed for a return to their cultural roots.

Fictionalized accounts of these events are known as Chūshingura. The story was popularized in numerous plays including bunraku and kabuki. Because of the censorship laws of the shogunate in the Genroku era, wssshich forbade portrayal of current events, the names were changed. While the version given by the playwrights may have come to be accepted as historical fact by some, the Chūshingura was written some 50 years after the event, and numerous historical records about the actual events that pre-date the Chūshingura survive. The popularity of the story is still high today. With ten different television productions in the years 1997–2007 alone, the Chūshingura ranks among the most familiar of all stories in Japan.

The bakufu's censorship laws had relaxed somewhat 75 years later, when Japanologist Isaac Titsingh first recorded the story of the 47 ronin as one of the significant events of the Genroku era.[2] Test.

The story of forty-seven samurai

[edit]In 1701 (by the Western calendar), two daimyo, Asano Takumi-no-Kami Naganori, the young daimyo of the Akō Domain (a small fiefdom in western Honshū), and Lord Kamei of the Tsuwano Domain, were ordered to arrange a fitting reception for the envoys of the Emperor in Edo, during their sankin kōtai service to the Shogun.[3]

These daimyo names are not fictional, nor is there any question that something actually happened in Genroku 15, on the 14th day of the 12th month (元禄十五年十二月十四日?, Tuesday, January 30, 1703).[4] What is commonly called the Akō incident was an actual event.[2]

For many years, the version of events retold by A. B. Mitford in Tales of Old Japan (1871) was considered authoritative. The sequence of events and the characters in this narrative were presented to a wide popular readership in the West. Mitford invited his readers to construe his story of the Forty-seven Ronin as historically accurate; and while his version of the tale has long been considered a standard work, some of its precise details are now questioned.[5] Nevertheless, even with plausible defects, Mitford's work remains a conventional starting point for further study.[5]

Whether as a mere literary device or as a claim for ethnographic veracity, Mitford explains:

In the midst of a nest of venerable trees in Takanawa, a suburb of Yedo, is hidden Sengakuji, or the Spring-hill Temple, renowned throughout the length and breadth of the land for its cemetery, which contains the graves of the Forty-seven Rônin, famous in Japanese history, heroes of Japanese drama, the tale of whose deed I am about to transcribe.

— Mitford, A. B.[6] [emphasis added]

Mitford appended what he explained were translations of Sengakuji documents the author had examined personally. These were proffered as "proofs" authenticating the factual basis of his story.[7] These documents were:

- ...the receipt given by the retainers of Kira Kôtsuké no Suké's son in return for the head of their lord's father, which the priests restored to the family.[8]

- ...a document explanatory of their conduct, a copy of which was found on the person of each of the forty-seven men, dated in the 15th year of Genroku, 12th month.[9]

- ...a paper which the Forty-seven Rǒnin laid upon the tomb of their master, together with the head of Kira Kôtsuké no Suké.[10]

(See Tales of Old Japan for the widely-known, yet significantly fictional narrative)

Genesis of a tragedy

[edit]

Asano and Kamei were to be given instruction in the necessary court etiquette by Kira Kozuke-no-Suke Yoshinaka, a powerful Edo official in the hierarchy of Tokugawa Tsunayoshi's shogunate. He became upset at them, allegedly because of either the small presents they offered him (in the time-honored compensation for such an instructor), or because they would not offer bribes as he wanted. Other sources say that he was a naturally rude and arrogant individual, or that he was corrupt, which offended Asano, a devoutly moral Confucian. Regardless, whether Kira treated them poorly, insulted them or failed to prepare them for fulfilling specific bakufu duties,[11] offense was taken.[2]

While Asano bore all this stoically, Kamei became enraged, and prepared to kill Kira to avenge the insults. However, the quick thinking counsellors of Kamei averted disaster for their lord and clan (for all would have been punished if Kamei killed Kira) by quietly giving Kira a large bribe; Kira thereupon began to treat Kamei nicely, which calmed Kamei's anger.[12]

However, Kira allegedly continued to treat Asano harshly, because he was upset that the latter had not emulated his companion. Finally, Kira insulted Asano, calling him a country boor with no manners, and Asano could restrain himself no longer. At the Matsu no Ōrōka, the main grand corridor that interconnects different parts of the shogun's residence, he lost his temper and attacked Kira with a dagger, but only wounded him in the face with his first strike; his second missed and hit a pillar. Guards then quickly separated them.[13]

Kira's wound was hardly serious, but the attack on a shogunate official within the boundaries of the shogun's residence was considered a grave offense. Any kind of violence, even drawing a sword, was completely forbidden in Edo Castle.[14] The daimyo of Akō had removed his dagger from its scabbard within Edo Castle, and for that offense, he was ordered to kill himself by committing seppuku.[2] Asano's goods and lands were to be confiscated after his death, his family was to be ruined, and his retainers were to be made ronin.

This news was carried to Ōishi Kuranosuke Yoshio, Asano's principal counsellor, who took command and moved the Asano family away, before complying with bakufu orders to surrender the castle to the agents of the government.

The ronin plot revenge

[edit]

Of Asano's over three hundred men, forty-seven (some sources say there were more than fifty, originally)—and especially their leader Ōishi—refused to allow their lord to go unavenged, even though revenge had been prohibited in the case. They banded together, swearing a secret oath to avenge their master by killing Kira, even though they knew they would be severely punished for doing so.

However, Kira was well guarded, and his residence had been fortified, to prevent just such an event. They saw that they would have to put him off his guard before they could succeed. To quell the suspicions of Kira and other shogunate authorities, they dispersed and became tradesmen or monks.

Ōishi himself took up residence in Kyoto, and began to frequent brothels and taverns, as if nothing were further from his mind than revenge. Kira still feared a trap, and sent spies to watch the former retainers of Asano.

One day, as Ōishi returned drunk from some haunt, he fell down in the street and went to sleep, and all the passers-by laughed at him. A Satsuma man, passing by, was infuriated by this behaviour on the part of a samurai—both by his lack of courage to avenge his master, as well as his current debauched behaviour. The Satsuma man abused and insulted him, and kicked him in the face (to even touch the face of a samurai was a great insult, let alone strike it), and spat on him.

Not too long after, Ōishi went to his loyal wife of twenty years and divorced her so that no harm would come to her when they took revenge, and sent her away with their two younger children to live with her parents; for the eldest boy, Chikara, he gave a choice to stay and fight or to leave. He remained with his father.

Ōishi began to act oddly and very unlike the composed samurai. He frequented geisha houses (particularly the Ichiriki Ochaya), drank nightly, and acted very obscenely in public. Later Ōishi's men bought a geisha, in hopes he would calm down. This was all a ruse to rid Ōishi of his spies.

Kira's agents reported all this to Kira, who became convinced that he was safe from the retainers of Asano, who must all be bad samurai indeed, without the courage to avenge their master after a year and a half. Thinking them harmless and lacking funds from his "retirement", he then reluctantly let down his guard.

The rest of the faithful ronin now gathered in Edo, and in their roles as workmen and merchants gained access to Kira's house, becoming familiar with the layout of the house and the character of all within. One of the retainers (Kinemon Kanehide Okano) went so far as to marry the daughter of the builder of the house, to obtain plans. All of this was reported to Ōishi. Others gathered arms and secretly transported them to Edo, another offense.

The attack

[edit]

Two years later, when Ōishi was convinced that Kira was thoroughly off his guard,[15] and everything was ready, he fled from Kyoto, avoiding the spies who were watching him, and the entire band gathered at a secret meeting-place in Edo, and renewed their oaths.

In Genroku 15, on the 14th day of the 12th month (元禄十五年十二月十四日?, Tuesday, January 30, 1703),[4] early in the morning in a driving wind during a heavy fall of snow, Ōishi and the ronin attacked Kira Yoshinaka's mansion in Edo. According to a carefully laid-out plan, they split up into two groups and attacked, armed with swords and bows. One group, led by Ōishi, was to attack the front gate; the other, led by his son, Ōishi Chikara, was to attack the house via the back gate. A drum would sound the simultaneous attack, and a whistle would signal that Kira was dead.[16]

Once Kira was dead, they planned to cut off his head, and lay it as an offering on their master's tomb. They would then turn themselves in, and wait for their expected sentence of death.[17] All this had been confirmed at a final dinner, where Ōishi had asked them to be careful, and spare women, children, and other helpless people.[18] The code of bushido does not require mercy to noncombatants, nor forbid it.

Ōishi had four men scale the fence and enter the porter's lodge, capturing and tying up the guard there.[19] He then sent messengers to all the neighboring houses, to explain that they were not robbers, but retainers out to avenge the death of their master, and that no harm would come to anyone else: they were all perfectly safe. One of the ronin climbed to the roof, and loudly announced to the neighbors that the matter is a revenge act (katakiuchi, 敵討ち). The neighbors, who all hated Kira, were relieved and did nothing to hinder the raiders.[20]

After posting archers (some on the roof), to prevent those in the house (who had not yet awakened) from sending for help, Ōishi sounded the drum to start the attack. Ten of Kira's retainers held off the party attacking the house from the front, but Ōishi Chikara's party broke into the back of the house.[21]

Kira, in terror, took refuge in a closet in the veranda, along with his wife and female servants. The rest of his retainers, who slept in barracks outside, attempted to come into the house to his rescue. After overcoming the defenders at the front of the house, the two parties of father and son joined up, and fought with the retainers who came in. The latter, perceiving that they were losing, tried to send for help, but their messengers were killed by the archers posted to prevent that eventuality.[22]

Eventually, after a fierce struggle, the last of Kira's retainers was subdued; in the process they killed sixteen of Kira's men and wounded twenty-two, including his grandson. Of Kira, however, there was no sign. They searched the house, but all they found were crying women and children. They began to despair, but Ōishi checked Kira's bed, and it was still warm, so he knew he could not be far.[23]

The death of Kira

[edit]A renewed search disclosed an entrance to a secret courtyard hidden behind a large scroll; the courtyard held a small building for storing charcoal and firewood, where two more hidden armed retainers were overcome and killed. A search of the building disclosed a man hiding; he attacked the searcher with a dagger, but the man was easily disarmed.[24]

He refused to say who he was, but the searchers felt sure it was Kira, and sounded the whistle. The ronin gathered, and Ōishi, with a lantern, saw that it was indeed Kira—as a final proof, his head bore the scar from Asano's attack.[25]

At that, Ōishi went on his knees, and in consideration of Kira's high rank, respectfully addressed him, telling him they were retainers of Asano, come to avenge him as true samurai should, and inviting Kira to die as a true samurai should, by killing himself. Ōishi indicated he personally would act as a second, and offered him the same dagger that Asano had used to kill himself.[26]

However, no matter how much they entreated him, Kira crouched, speechless and trembling. At last, seeing it was useless to ask, Ōishi ordered the ronin to pin him down, and killed him by cutting off his head with the dagger. Kira was killed on the night of the 14th day of the 12th month of the 15th year of Genroku (1703-01-30 Gregorian[27]).

They then extinguished all the lamps and fires in the house (lest any cause the house to catch fire, and start a general fire that would harm the neighbors), and left, taking the head.[28]

One of the ronin, the ashigaru Terasaka Kichiemon, was ordered to travel to Akō and inform them that their revenge had been completed. (Though Kichiemon's role as a messenger is the most widely-accepted version of the story, other accounts have him running away before or after the battle, or being ordered to leave before the ronin turned themselves in.)[29]

The aftermath

[edit]

As day was now breaking, they quickly carried Kira's head from his residence to their lord's grave in Sengaku-ji temple, marching about 10 kilometers across the city, causing a great stir on the way. The story quickly went around as to what had happened, and everyone on their path praised them, and offered them refreshment.[30]

On arriving at the temple, the remaining forty-six ronin washed and cleaned Kira's head in a well, and laid it, and the fateful dagger, before Asano's tomb. They then offered prayers at the temple, and gave the abbot of the temple all the money they had left, asking him to bury them decently, and offer prayers for them. They then turned themselves in; the group was broken into four parts and put under guard of four different daimyo.[31]

During this time, two friends of Kira came to collect his head for burial; the temple still has the original receipt for the head, which the friends and the priests who dealt with them all signed.[8]

The shogunate officials in Edo were in a quandary. The samurai had followed the precepts of bushido by avenging the death of their lord; but they had also defied the shogunate authority by exacting revenge, which had been prohibited. In addition, the Shogun received a number of petitions from the admiring populace on behalf of the ronin. As expected, the ronin were sentenced to death for the murder of Kira; but the Shogun had finally resolved the quandary by ordering them to honorably commit seppuku, instead of having them executed as criminals.[32] It is known that each of the assailants ended his life in a ritualistic fashion.[2]

Each of the forty-six ronin killed himself in Genroku 16, on the 4th day of the 2nd month (元禄十六年二月四日?, Tuesday, March 20, 1703).[4] This has caused a considerable amount of confusion ever since, with some people referring to the "forty-six ronin"; this refers to the group put to death by the Shogun, the actual attack party numbered forty-seven. The forty-seventh ronin, identified as Terasaka Kichiemon, eventually returned from his mission and was pardoned by the Shogun (some say on account of his youth). He lived until the age of 87, dying in around 1747, and was then buried with his comrades. The assailants who died by seppuku were subsequently interred on the grounds of Sengaku-ji,[2] in front of the tomb of their master.[32]

The clothes and arms they wore are still preserved in the temple to this day, along with the drum and whistle; the armor was all home-made, as they had not wanted to possibly arouse suspicion by purchasing any.

The tombs became a place of great veneration, and people flocked there to pray. The graves at this temple have been visited by a great many people throughout the years since the Genroku era.[2] One of those who visited the tombs was the man who had mocked and spat on Ōishi as he lay drunk in the street. Addressing the grave, he begged for forgiveness for his actions, and for thinking that Ōishi was not a true samurai. He then committed suicide, and is buried next to the graves of the ronin.[32]

Re-establishment of the Asano clan's lordship

[edit]Though this act is often viewed as an act of loyalty, there had been a second goal, to re-establish the Asanos' lordship and finding a place to serve for fellow samurai. Hundreds of samurai who had served under Asano had been left jobless and many were unable to find employment, as they had served under a disgraced family. Many lived as farmers or did simple handicrafts to make ends meet. The 47 ronin's act cleared their names and many of the unemployed samurai found jobs soon after the ronin had been sentenced to their honorable end.

Asano Daigaku Nagahiro, Takuminokami's younger brother and heir, was allowed by the Tokugawa Shogunate to re-establish his name, though his territory was reduced to a tenth of the original.

Criticism

[edit]The ronin spent a year waiting for the "right time" for their revenge. It was Yamamoto Tsunetomo, author of the Hagakure, who asked this famous question: "What if, nine months after Asano's death, Kira had died of an illness?" The answer obviously is: then the Forty-seven Ronin would have lost their only chance at avenging their master. Even if they had claimed, then, that their dissipated behavior was just an act, that in just a little more time they would have been ready for revenge, who would have believed them? They would have been forever remembered as cowards and drunkards—bringing eternal shame to the name of the Asano clan. The right thing for the ronin to do, wrote Yamamoto, according to proper bushido, was to attack Kira and his men immediately after Asano's death. The ronin would probably have suffered defeat, as Kira was ready for an attack at that time — but this was unimportant. Ōishi, from the perspective of bushido, was too obsessed with success. He conceived his convoluted plan to ensure they would succeed at killing Kira, which is not a proper concern in a samurai: the important thing was not the death of Kira, but for the former samurai of Asano to show outstanding courage and determination in an all-out attack against the Kira house, thus winning everlasting honor for their dead master. Even if they failed to kill Kira, even if they all perished, it wouldn't have mattered, as victory and defeat have no importance in bushido. By waiting a year they improved their chances of success but risked dishonoring the name of their clan, the worst sin a samurai can commit. This is why Yamamoto and others claim that the tale of the Forty-seven Ronin is a good story of revenge — but by no means a story of bushido.[33]

Yamamoto was not the only one to find fault in Ōishi's actions. Below are other authors' criticisms of the events surrounding Asano's attack on Kira and the subsequent attack on Kira's mansion by the forty-seven ronin.

This section is in a list format that may be better presented using prose. (February 2011) |

- Asano Naganori showed concern neither for the reputation of his house nor the fate of his family and retainers when he attacked Kira. Asano should have known that attacking a Shogunal official in the Shogun's castle was a grave offence that likely would result in his death and the destruction of his house and confiscation of his domain thereby destroying the livelihood of his loyal retainers.

- Asano was a student of Confucian scholar Yamaga Soko, whose principal teaching was that in peacetime the samurai "should set a high example of devotion to duty". However, although apprenticed to Soko in the military arts, Asano showed a marked lack of samurai spirit as well as a lack of sword skill in his attack on Kira. Asano attacked Kira from behind while Kira was engaged in a discussion and Asano did not succeed in killing Kira. This showed neither courage nor ability.

- There is no evidence in legitimate historical documents that shows that Kira Yoshinaka was the villain so often portrayed that would justify an attack on him in the Shogun's castle. But Kira had to become the villain to make the story of the 47 Loyal Ronin what it was. Little is ever mentioned of Kira's 40 year service in a responsible government position, only that he was a greedy official who gravely insulted Asano. There is no evidence to support either of those assertions.

- It has been argued by some that since the 47 Ronin knowingly violated the law of the Bakufu when they attacked Kira's mansion, it was absurd for the samurai to notify the authorities on completion of their crime with the message that they were now awaiting their orders rather than immediately committing seppuku. This leads some to suspect that the driving force was not the revenge of their dead lord but the hope that praise and admiration for this act of "loyalty" would secure them a pardon and reemployment elsewhere. If they had not expected to live, why did they not disembowel themselves immediately on completion of their revenge?

- With a year and a half between Asano Naganori's death and the slaying of Kira, some had wondered whether the revenge was really a priority of Ōishi Kuranosuke, the chief retainer of Asano Naganori. Of course the story goes that it was all part of Kuranosuke's plan to lull Kira into complacency. Yet the point has been made of the elaborate preparations for the attack in the dead of the night, after Kira's staff was tired out by entertaining guests and when snow muffled the footsteps of the attackers. Some contemporaries such as Sato Naotaka and Dazai Shundai thought such trickery was unworthy of a samurai.

- Kira, according to his income, was a man of lowly hatamoto status. The fact that 16 of his retainers were killed in the attack, while only 4 attackers received relatively light wounds, indicated that this was an unequal battle. The large loss of life among the Kira retainers and servants could have been avoided in a spirited day-time attack on Kira on the open road by just a few men in traditional samurai fashion. In such an assault the attackers would, however, most likely have been cut down immediately afterwards and the chance of a pardon lost. The Bakufu's charge against the 47 Ronin after the incident explicitly mentions the use of projectile weapons, which could mean anything from arrows and catapults to firearms. It may also refer to spears. This clearly gave the attackers an advantage against the Kira retainers who were probably armed only with swords.

- Consideration should be also given to the public emphasis on loyalty and filial piety. The 47 Ronin certainly must have been aware that at times Shogun Tokugawa Tsunayoshi would overturn decisions of his officials to heap praise and rewards on people who in his opinion had lived up to these ideals particularly well. The suggestion that the Ako samurai did not commit suicide but gave themselves up to the authorities in the hope of being singled out for such shogunal praise was not altogether unlikely at the time.

The Forty-Seven Ronin in the arts

[edit]The tragedy of the Forty-seven Ronin has been one of the most popular themes in Japanese art, and has lately even begun to make its way into Western art.

Immediately following the event, there were mixed feelings among the intelligentsia about whether such vengeance had been appropriate—many agreed that, given their master's last wishes, the forty-seven had done the right thing, but were undecided about whether such a vengeful wish was proper. Over time, however, the story became a symbol, not of bushido, as the forty-seven can be seen as seriously lacking it, but of loyalty to one's master and later, of loyalty to the emperor. Once this happened, it flourished as a subject of drama, storytelling, and visual art.

Plays

[edit]The incident immediately inspired a succession of kabuki and bunraku plays; the first, The Night Attack at Dawn by the Soga appeared only two weeks after they died. It was shut down by the authorities, but many others soon followed, initially especially in Osaka and Kyoto, further away from the capital. Some even took it as far as Manila, to spread the story to the rest of Asia.

The most successful of them was a bunraku puppet play called Kanadehon Chūshingura (now simply called Chūshingura, or "Treasury of Loyal Retainers"), written in 1748 by Takeda Izumo and two associates; it was later adapted into a kabuki play, which is still one of Japan's most popular.

In the play, to avoid the attention of the censors, the events are transferred into the distant past, to the 14th century reign of shogun Ashikaga Takauji. Asano became Enya Hangan Takasada, Kira became Ko no Moronao and Ōishi rather transparently became Ōboshi Yuranosuke Yoshio; the names of the rest of the ronin were disguised to varying degrees. The play contains a number of plot twists that do not reflect the real story: Moronao tries to seduce Enya's wife, and one of the ronin dies before the attack because of a conflict between family and warrior loyalty (another possible cause of the confusion between forty-six and forty-seven).

Opera

[edit]The story was turned into an opera, Chūshingura, by Shigeaki Saegusa in 1997.

Cinema and television

[edit]The play has been made into a movie at least six times,[34] the earliest starring Onoe Matsunosuke. The film's release date is questioned, but placed between 1910 and 1917. It has been aired on the Jidaigeki Senmon Channel (Japan) with accompanying benshi narration. In 1941 the Japanese military commissioned director Kenji Mizoguchi (Ugetsu) to make The 47 Ronin. They wanted a ferocious morale booster based upon the familiar rekishi geki ("historical drama") of The Loyal 47 Ronin. Instead, Mizoguchi chose for his source Mayama Chūshingura, a cerebral play dealing with the story. The 47 Ronin was a commercial failure, having been released in Japan one week before the Attack on Pearl Harbor. The Japanese military and most audiences found the first part to be too serious, but the studio and Mizoguchi both regarded it as so important that Part Two was put into production, despite Part One's lukewarm reception. Renowned by postwar scholars lucky to have seen it in Japan, The 47 Ronin wasn't shown in America until the 1970s.[35]

The 1962 version directed by Hiroshi Inagaki, Chūsingura, is most familiar to Western audiences.[34] In this, Toshirō Mifune appears in a supporting role as spearsman Tawaraboshi Genba. Mifune was to revisit the story several times in his career. In 1971 he appeared in the 52-part television series Daichūshingura as Ōishi, while in 1978 he appeared as Lord Tsuchiya in the epic Swords Of Vengeance, aka Ako-Jo danzetsu.

Many Japanese television shows, including single programs, short series, single seasons, and even year-long series such as Daichūshingura and the more recent NHK Taiga drama Genroku Ryōran, recount the events of the Forty-seven Ronin. Among both films and television programs, some are quite faithful to the Chūshingura, while others incorporate unrelated material or alter details. In addition, gaiden dramatize events and characters not in the Chūshingura. Kon Ichikawa directed another version in 1994. In 2004, Saito Mitsumasa directed a 9-episode mini-series starring Matsudaira Ken, who also starred in a 1999 49-episode TV series of the Chūshingura entitled Genroku Ryoran. In Hirokazu Koreeda's 2006 film Hana yori mo naho, the event of the 47 ronin was used as a backdrop in the story, one of the ronin being a neighbour of the protagonists.

The Hollywood film 47 Ronin is currently under production by Universal Pictures and will star Keanu Reeves as an outcast who joins the samurai in their quest to avenge their slain master along with some of the biggest Japanese actors such as Hiroyuki Sanada, Tadanobu Asano, Kô Shibasaki, Rinko Kikuchi, and Akanishi Jin. The film is scheduled to be released on November 21, 2012.

Woodblock prints

[edit]The Forty-seven Ronin are one of the most popular themes in woodblock prints, or ukiyo-e; the list of artists who have done prints portraying either the original events, or scenes from the play, or the actors, is a Who's Who of woodblock artists. One book on subjects depicted in woodblock prints devotes no less than seven chapters to the history of the appearance of this theme in woodblocks.

Among the artists who produced prints on this subject are Utamaro, Toyokuni, Hokusai, Kunisada, Hiroshige and Yoshitoshi. However, probably the most famous woodblocks in the genre are those of Kuniyoshi, who produced at least eleven separate complete series on this subject, along with more than twenty triptychs.

In the West

[edit]- The earliest known account of the Akō incident in the West was published in 1822 in Isaac Titsingh's posthumous book, Illustrations of Japan.[2]

- A widely popularized retelling of the Akō story appeared in 1871 in A.B. Mitford's Tales of Old Japan.

- Jorge Luis Borges retold the story in his first short story collection, A Universal History of Infamy, under the title "The Uncivil Teacher of Etiquette, Kotsuke no Suke."

- Lucia St. Clair Robson's historical fiction novel The Tokaido Road is adapted from the tale of the Forty-seven Ronin.

- John Frankenheimer's movie Ronin has a scene in which the story of the 47 ronin is told, thus explaining the origin of the movie title.

- The novel The Fifth Profession by David Morrell mentions the tale of the 47 ronin to show ultimate loyalty even beyond death as this is the overall theme of the book.

- The German fantasy thriller Der Sommer des Samurai ("Summer of the Samurai") uses the story of Ōishi Yoshio and his ronin to add to the plot's mysticism, which revolves around the recovery of Yoshio's katana forged by Muramasa, which was stolen by a band of dishonest German industrialists.

- In 2007, writer Stephen Hunter told the story in the book, The 47th Samurai, of the Muramasa Blade that became a military sword in WW2 then was the source of a great adventure for character Bob Lee Swagger. Through a twist of fate, Bob Lee becomes the 47th Samurai himself when he joins 45 soldiers (whose leader has been killed, too) and a CIA woman to do battle in a snowy scene resembling the battle that started it all.

Gallery

[edit]-

Memorial to the unswerving loyalty of Oishi Yoshio and 16 others, at the site where they died.

-

Incense burns at the graves of the 47 Ronin at Sengaku-ji.

-

Graves of the 47 ronin.

-

Graves of the 47 ronin.

-

Entrance to Sengaku-ji

-

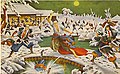

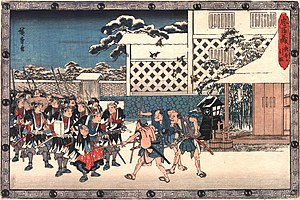

Woodcut by Kunisada depicting the attack (early 1800s).

-

Postcard depicting the attack, early 1920s.

-

Poster for 1958 film adaptation.

-

Another poster for the 1958 film.

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Kanadehon". Columbia University.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Screech, T. (2006). Secret Memoirs of the Shoguns: Isaac Titsingh and Japan, p. 91.

- ^ Mitford, A. B. (1871). Tales of Old Japan, p. 7.

- ^ a b c Tsuchihashi conversion

- ^ a b Analysis of Mitford's story by Dr. Henry Smith, Chushinguranew website, Columbia University

- ^ (1871). Tales of Old Japan, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Mitford, pp. 28–34.

- ^ a b Mitford, p. 30.

- ^ Mitford, 31.

- ^ Mitford, 32.

- ^ Mitford, p. 7.

- ^ Mitford, pp. 8–10.

- ^ Mitford, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Mitford, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Mitford, p. 16.

- ^ Mitford, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Mitford, p. 17

- ^ Mitford, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Mitford, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Mitford, p. 19.

- ^ Mitford, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Mitford, p. 20.

- ^ Mitford, p. 22.

- ^ Mitford, p. 23.

- ^ Mitford, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Mitford, p. 24.

- ^ Date conversion by NengoCalc.

- ^ Mitford, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Smith, Henry D. II (2004). "The Trouble with Terasaka: The Forty-Seventh Ronin and the Chushingura Imagination" (PDF). Japan Review: 16:3–65.

- ^ Mitford, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Mitford, pp. 26–27.

- ^ a b c Mitford, p. 28.

- ^ Yamamoto, T. (Kodansha, 1979). Hagakure, pph. 26.

- ^ a b Child, Ben. "Keanu Reeves to play Japanese samurai in 47 Ronin," The Guardian (London). December 9, 2008.

- ^ "Movies". Chicago Reader.

References

[edit]- Allyn, John. (1981). The Forty-Seven Ronin Story. New York.

- Dickens, Frederick V. (1930) Chushingura, or The Loyal League. London.

- Keene, Donald. (1971). Chushingura: A Puppet Play. New York.

- Mitford, Algernon Bertram Freeman-Mitford, Lord Redesdale (1871). Tales of Old Japan. London: University of Michigan.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Robinson, B.W. (1982). Kuniyoshi: The Warrior Prints. Ithaca.

- Sato, Hiroaki. (1995). Legends of the Samurai. New York.

- Screech, Timon. (2006). Secret Memoirs of the Shoguns: Isaac Titsingh and Japan, 1779–1822. London.

- Steward, Basil. (1922). Subjects Portrayed in Japanese Colour-Prints. New York.

- Titsingh, Isaac. (1820). Mémoires et Anecdotes sur la Dynastie régnante des Djogouns, Souverains du Japon. Paris: Nepveu.

- Weinberg, David R. et al. (2001). Kuniyoshi: The Faithful Samurai. Leiden.

External links

[edit]- Robson, Lucia St. Clair (1991) The Tokaido Road. Forge Books. New York.

- Chushingura and the Samurai Tradition — Comparisons of the accuracy of accounts by Mitford, Murdoch and others, as well as much other useful material, by a noted scholars of Japan

- Ako's Forty-Seven Samurai — Web site produced by students at Ako High School; contains the story of the 47 Ronin's story, and images of wooden votive tablets of the 47 Ronin in the Oishi Shrine, Ako

- The Trouble with Terasaka: The Forty-Seventh Ronin and the Chushingura Imagination by Henry D. Smith II, Japan Review, 2004, 16:3-65

- Well photos — The well where 47 Ronin washed the head of Kira

- Five different woodblock print versions of the story by Ando Hiroshige

- National Diet Library: photograph of Sengaku-ji (1893); photograph of Sengaku-ji (1911)

- Yoshitoshi, 47 Ronin series (1860)

Further reading

[edit]- Turnbull, Stephen. (2011). The Revenge of the 47 Ronin, Edo 1703; Osprey Raid Series #23, Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84908-427-7

br:Ar 47 ronin id:Empat puluh tujuh Ronin it:Quarantasette Rōnin ms:Empat puluh tujuh Ronin pt:47 rōnin ro:Cei patruzeci și șapte de ronini fi:47 rōninia

- Articles with missing files

- Pages using the JsonConfig extension

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles containing Japanese-language text

- Articles needing additional references from February 2011

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- All articles needing additional references

- Articles needing cleanup from February 2011

- All pages needing cleanup

- Articles with sections that need to be turned into prose from February 2011

- CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list

- Traditional stories

- Samurai who committed suicide

- Seppuku

- Mass suicides

- Articles about multiple people

- Quantified human groups

- Edo period

- Japanese folklore