Watergate scandal

The Watergate scandal was a major political scandal in the United States involving the administration of President Richard Nixon from 1972 to 1974 that led to Nixon's resignation. The scandal stemmed from the Nixon administration's persistent attempts to cover up its involvement in the June 17, 1972 burglary of the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Washington, D.C., Watergate Office Building.

After the five perpetrators were arrested, the press and the Department of Justice connected the cash found on them at the time to the Committee for the Re-Election of the President.[1][2] Further investigations, along with revelations during subsequent trials of the burglars, led the House of Representatives to grant the U.S. House Judiciary Committee additional investigative authority—to probe into "certain matters within its jurisdiction",[3][4] and led the Senate to create the U.S. Senate Watergate Committee, which held hearings. Witnesses testified that Nixon had approved plans to cover up his administration's involvement in the burglary, and that there was a voice-activated taping system in the Oval Office.[5][6] Throughout the investigation, Nixon's administration resisted its probes, and this led to a constitutional crisis.[7] The Senate Watergate hearings were broadcast "gavel-to-gavel" nationwide by PBS and aroused public interest.[8]

Several major revelations and egregious presidential actions obstructing the investigation later in 1973 prompted the House to commence an impeachment process against Nixon.[9] The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Nixon had to release the Oval Office tapes to government investigators. The Nixon White House tapes revealed that he had conspired to cover up activities that took place after the burglary and had later tried to use federal officials to deflect attention from the investigation.[10][11] The House Judiciary Committee approved three articles of impeachment against Nixon for obstruction of justice, abuse of power, and contempt of Congress. With his complicity in the cover-up made public, and his political support completely eroded, Nixon resigned from office under Section 1 of the 25th Amendment on August 9, 1974. It is generally believed that, if he had not done so, he would have been the second president impeached by the House, after Andrew Johnson in 1868, the first federal official impeached since Halsted Ritter in 1936, and the first and only one to be removed from office by a trial in the Senate.[12][13] He is the only U.S. president to have resigned from office. On September 8, 1974, his successor, Gerald Ford, pardoned him.

There were 69 people indicted and 48 people—many of them top Nixon administration officials—convicted.[14] The metonym Watergate came to encompass an array of clandestine and often illegal activities undertaken by members of the Nixon administration, including bugging the offices of political opponents and people of whom Nixon or his officials were suspicious; ordering investigations of activist groups and political figures; and using the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Central Intelligence Agency, and the Internal Revenue Service as political weapons.[15] The use of the suffix -gate after an identifying term has since become synonymous with public scandal,[16][17][18] especially political scandal.[19][20]

Wiretapping of the Democratic Party's headquarters

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2021) |

On January 27, 1972, G. Gordon Liddy, Finance Counsel for the Committee for the Re-Election of the President (CRP) and former aide to John Ehrlichman, presented a campaign intelligence plan to CRP's acting chairman Jeb Stuart Magruder, Attorney General John Mitchell, and Presidential Counsel John Dean that involved extensive illegal activities against the Democratic Party. According to Dean, this marked "the opening scene of the worst political scandal of the twentieth century and the beginning of the end of the Nixon presidency".[21]

Mitchell viewed the plan as unrealistic. Two months later, Mitchell approved a reduced version of the plan, including burglarizing the Democratic National Committee's (DNC) headquarters at the Watergate Complex in Washington, D.C. to photograph campaign documents and install listening devices in telephones. Liddy was nominally in charge of the operation,[citation needed] but has since insisted that he was duped by both Dean and at least two of his subordinates, which included former CIA officers E. Howard Hunt and James McCord, the latter of whom was serving as then-CRP Security Coordinator after John Mitchell had by then resigned as attorney general to become the CRP chairman.[22][23]

In May, McCord assigned former FBI agent Alfred C. Baldwin III to carry out the wiretapping and monitor the telephone conversations afterward.[24] Template:Citation needed span

On May 11, McCord arranged for Baldwin, whom investigative reporter Jim Hougan described as "somehow special and perhaps well known to McCord," to stay at the Howard Johnson's motel across the street from the Watergate complex.[25] Room 419 was booked in the name of McCord's company.[25] At the behest of Liddy and Hunt, McCord and his team of burglars prepared for their first Watergate break-in, which began on May 28.[26]

Two phones inside the DNC headquarters' offices were said to have been wiretapped.[27] One was Robert Spencer Oliver's phone. At the time, Oliver was working as the executive director of the Association of State Democratic Chairmen. The other phone belonged to DNC chairman Larry O'Brien. The FBI found no evidence that O'Brien's phone was bugged;[28] however, it was determined that an effective listening device was installed in Oliver's phone. While successful with installing the listening devices, the committee agents soon determined that they needed repairs. They plotted a second "burglary" in order to take care of the situation.[27]

Sometime after midnight on Saturday, June 17, 1972, Watergate Complex security guard Frank Wills noticed tape covering the latches on some of the complex's doors leading from the underground parking garage to several offices, which allowed the doors to close but stay unlocked. He removed the tape, believing it was nothing.[29] When he returned a short time later and discovered that someone had retaped the locks, he called the police.[29] Responding to the call was an unmarked police car with three plainclothes officers (Sgt. Paul W. Leeper, Officer John B. Barrett, and Officer Carl M. Shoffler) working the overnight "bum squad"—dressed as hippies and on the lookout for drug deals and other street crimes.[30] Alfred Baldwin, on "spotter" duty at the Howard Johnson's hotel across the street, was distracted watching the film Attack of the Puppet People on TV and did not observe the arrival of the police car in front of the Watergate building,[30] nor did he see the plainclothes officers investigating the DNC's sixth floor suite of 29 offices. By the time Baldwin finally noticed unusual activity on the sixth floor and radioed the burglars, it was already too late.[30]

The police apprehended five men, later identified as Virgilio Gonzalez, Bernard Barker, James McCord, Eugenio Martínez, and Frank Sturgis.[22] They were charged with attempted burglary and attempted interception of telephone and other communications. The Washington Post reported the day after that "police found lock-picks and door jimmies, almost $2,300 in cash, most of it in $100 bills with the serial numbers in sequence ... a shortwave receiver that could pick up police calls, 40 rolls of unexposed film, two 35 millimeter cameras and three pen-sized tear gas guns".[31] The Post would later report that the actual amount of cash was "[a]bout 53 of these $100 bills were found on the five men after they were arrested at the Watergate."[32]

The following morning, Sunday, June 18, G. Gordon Liddy called Jeb Magruder in Los Angeles and informed him that "the four men arrested with McCord were Cuban freedom fighters, whom Howard Hunt recruited". Initially, Nixon's organization and the White House quickly went to work to cover up the crime and any evidence that might have damaged the president and his reelection.[33]

On September 15, 1972, a grand jury indicted the five office burglars, as well as Hunt and Liddy,[34] for conspiracy, burglary, and violation of federal wiretapping laws. The burglars were tried by a jury, with Judge John Sirica officiating, and pled guilty or were convicted on January 30, 1973.[35]

Cover-up and its unraveling

[edit]Initial cover-up

[edit]

Within hours of the burglars' arrests, the FBI discovered E. Howard Hunt's name in Barker and Martínez's address books. Nixon administration officials were concerned because Hunt and Liddy were also involved in a separate secret activity known as the "White House Plumbers", which was established to stop security "leaks" and investigate other sensitive security matters. Dean later testified that top Nixon aide John Ehrlichman ordered him to "deep six" the contents of Howard Hunt's White House safe. Ehrlichman subsequently denied this. In the end, Dean and the FBI's Acting Director L. Patrick Gray (in separate operations) destroyed the evidence from Hunt's safe.

Nixon's own reaction to the break-in, at least initially, was one of skepticism. Watergate prosecutor James Neal was sure that Nixon had not known in advance of the break-in. As evidence, he cited a conversation taped on June 23 between the President and his chief of staff, H. R. Haldeman, in which Nixon asked, "Who was the asshole that did that?"[36] However, Nixon subsequently ordered Haldeman to have the CIA block the FBI's investigation into the source of the funding for the burglary.[citation needed]

A few days later, Nixon's press secretary, Ron Ziegler, described the event as "a third-rate burglary attempt". On August 29, at a news conference, Nixon stated that Dean had conducted a thorough investigation of the incident, when Dean had actually not conducted any investigations at all. Nixon furthermore said, "I can say categorically that ... no one in the White House staff, no one in this Administration, presently employed, was involved in this very bizarre incident." On September 15, Nixon congratulated Dean, saying, "The way you've handled it, it seems to me, has been very skillful, because you—putting your fingers in the dikes every time that leaks have sprung here and sprung there."[22]

Kidnapping of Martha Mitchell

[edit]Martha Mitchell was the wife of Nixon's Attorney General, John N. Mitchell, who had recently resigned his role so that he could become campaign manager for Nixon's Committee for the Re-Election of the President (CRP). John Mitchell was aware that Martha knew McCord, one of the Watergate burglars who had been arrested, and that upon finding out, she was likely to speak to the media. In his opinion, her knowing McCord was likely to link the Watergate burglary to Nixon. John Mitchell instructed guards in her security detail not to let her contact the media.[37]

In June 1972, during a phone call with United Press International reporter Helen Thomas, Martha Mitchell informed Thomas that she was leaving her husband until he resigned from the CRP.[38] The phone call ended abruptly. A few days later, Marcia Kramer, a veteran crime reporter of the New York Daily News, tracked Mitchell to the Westchester Country Club in Rye, New York, and described Mitchell as "a beaten woman" with visible bruises.[39] Mitchell reported that, during the week following the Watergate burglary, she had been held captive in a hotel in California, and that security guard Steve King ended her call to Thomas by pulling the phone cord from the wall.[39][38] Mitchell made several attempts to escape via the balcony, but was physically accosted, injured, and forcefully sedated by a psychiatrist.[40][41] Following conviction for his role in the Watergate burglary, in February 1975, McCord admitted that Mitchell had been "basically kidnapped", and corroborated her reports of the event.[42]

Money trail

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2016) |

On June 19, 1972, the press reported that one of the Watergate burglars was a Republican Party security aide.[43] Former attorney general John Mitchell, who was then the head of the Committee to Re-elect the President (CRP), denied any involvement with the Watergate break-in. He also disavowed any knowledge whatsoever of the five burglars.[44][45] On August 1, a $25,000 (approximately $131,000 in 2016 dollars) cashier's check was found to have been deposited in the US and Mexican bank accounts of one of the Watergate burglars, Bernard Barker. Made out to the finance committee of the Committee to Reelect the President, the check was a 1972 campaign donation by Kenneth H. Dahlberg. This money (and several other checks which had been lawfully donated to the CRP) had been directly used to finance the burglary and wiretapping expenses, including hardware and supplies.

Barker's multiple national and international businesses all had separate bank accounts, which he was found to have attempted to use to disguise the true origin of the money being paid to the burglars. The donor's checks demonstrated the burglars' direct link to the finance committee of the CRP.

Donations totaling $86,000 ($451,000 today) were made by individuals who believed they were making private donations by certified and cashier's checks for the president's re-election. Investigators' examination of the bank records of a Miami company run by Watergate burglar Barker revealed an account controlled by him personally had deposited a check and then transferred it through the Federal Reserve Check Clearing System.

The banks that had originated the checks were keen to ensure the depository institution used by Barker had acted properly in ensuring the checks had been received and endorsed by the check's payee, before its acceptance for deposit in Bernard Barker's account. Only in this way would the issuing banks not be held liable for the unauthorized and improper release of funds from their customers' accounts.

The investigation by the FBI, which cleared Barker's bank of fiduciary malfeasance, led to the direct implication of members of the CRP, to whom the checks had been delivered. Those individuals were the committee bookkeeper and its treasurer, Hugh Sloan.

As a private organization, the committee followed the normal business practice in allowing only duly authorized individuals to accept and endorse checks on behalf of the committee. No financial institution could accept or process a check on behalf of the committee unless a duly authorized individual endorsed it. The checks deposited into Barker's bank account were endorsed by Committee treasurer Hugh Sloan, who was authorized by the finance committee. However, once Sloan had endorsed a check made payable to the committee, he had a legal and fiduciary responsibility to see that the check was deposited only into the accounts named on the check. Sloan failed to do that. When confronted with the potential charge of federal bank fraud, he revealed that committee deputy director Jeb Magruder and finance director Maurice Stans had directed him to give the money to G. Gordon Liddy.

Liddy, in turn, gave the money to Barker and attempted to hide its origin. Barker tried to disguise the funds by depositing them into accounts in banks outside of the United States. Unbeknownst to Barker, Liddy, and Sloan, the complete record of all such transactions was held for roughly six months. Barker's use of foreign banks in April and May 1972 to deposit checks and withdraw the funds via cashier's checks and money orders, resulted in the banks keeping the entire transaction records until October and November 1972.

All five Watergate burglars were directly or indirectly tied to the 1972 CRP, thus causing Judge Sirica to suspect a conspiracy involving higher-echelon government officials.[46]

On September 29, 1972, the press reported that John Mitchell, while serving as attorney general, controlled a secret Republican fund used to finance intelligence-gathering against the Democrats. On October 10, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein of The Washington Post reported that the FBI had determined that the Watergate break-in was part of a massive campaign of political spying and sabotage on behalf of the Nixon re-election committee. Despite these revelations, Nixon's campaign was never seriously jeopardized; on November 7, the President was re-elected in one of the biggest landslides in American political history.

Role of the media

[edit]The connection between the break-in and the re-election committee was highlighted by media coverage—in particular, investigative coverage by The Washington Post, Time, and The New York Times. The coverage dramatically increased publicity and consequent political and legal repercussions. Relying heavily upon anonymous sources, Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein uncovered information suggesting that knowledge of the break-in, and attempts to cover it up, led deeply into the upper reaches of the Justice Department, FBI, CIA, and the White House. Woodward and Bernstein interviewed Judy Hoback Miller, the bookkeeper for Nixon's re-election campaign, who revealed to them information about the mishandling of funds and records being destroyed.[47][1]

Chief among the Post's anonymous sources was an individual whom Woodward and Bernstein had nicknamed Deep Throat; 33 years later, in 2005, the informant was identified as Mark Felt, deputy director of the FBI during that period of the 1970s, something Woodward later confirmed. Felt met secretly with Woodward several times, telling him of Howard Hunt's involvement with the Watergate break-in, and that the White House staff regarded the stakes in Watergate as extremely high. Felt warned Woodward that the FBI wanted to know where he and other reporters were getting their information, as they were uncovering a wider web of crimes than the FBI first disclosed. All the secret meetings between Woodward and Felt took place at an underground parking garage in Rosslyn over a period from June 1972 to January 1973. Prior to resigning from the FBI on June 22, 1973, Felt also anonymously planted leaks about Watergate with Time magazine, The Washington Daily News and other publications.[1][48]

During this early period, most of the media failed to understand the full implications of the scandal, and concentrated reporting on other topics related to the 1972 presidential election.[49] Most outlets ignored or downplayed Woodward and Bernstein's scoops; the crosstown Washington Star-News and the Los Angeles Times even ran stories incorrectly discrediting the Post's articles. After the Post revealed that H.R. Haldeman had made payments from the secret fund, newspapers like the Chicago Tribune and the Philadelphia Inquirer failed to publish the information, but did publish the White House's denial of the story the following day.[50] The White House also sought to isolate the Post's coverage by tirelessly attacking that newspaper while declining to criticize other damaging stories about the scandal from the New York Times and Time magazine.[50][1]

After it was learned that one of the convicted burglars had written to Judge Sirica alleging a high-level cover-up, the media shifted its focus. Time magazine described Nixon as undergoing "daily hell and very little trust". The distrust between the press and the Nixon administration was mutual and greater than usual due to lingering dissatisfaction with events from the Vietnam War. At the same time, public distrust of the media was polled at more than 40%.[49]

Nixon and top administration officials discussed using government agencies to "get" (or retaliate against) those they perceived as hostile media organizations.[49] Such actions had been taken before. At the request of Nixon's White House in 1969, the FBI tapped the phones of five reporters. In 1971, the White House requested an audit of the tax return of the editor of Newsday, after he wrote a series of articles about the financial dealings of Charles "Bebe" Rebozo, a friend of Nixon.[51]

The Administration and its supporters accused the media of making "wild accusations", putting too much emphasis on the story, and of having a liberal bias against the Administration.[1][49] Nixon said in a May 1974 interview with supporter Baruch Korff that if he had followed the liberal policies that he thought the media preferred, "Watergate would have been a blip."[52] The media noted that most of the reporting turned out to be accurate; the competitive nature of the media guaranteed widespread coverage of the far-reaching political scandal.[49]

Scandal escalates

[edit]Rather than ending with the conviction and sentencing to prison of the five Watergate burglars on January 30, 1973, the investigation into the break-in and the Nixon Administration's involvement grew broader. "Nixon's conversations in late March and all of April 1973 revealed that not only did he know he needed to remove Haldeman, Ehrlichman, and Dean to gain distance from them, but he had to do so in a way that was least likely to incriminate him and his presidency. Nixon created a new conspiracy—to effect a cover-up of the cover-up—which began in late March 1973 and became fully formed in May and June 1973, operating until his presidency ended on August 9, 1974."[53] On March 23, 1973, Judge Sirica read the court a letter from Watergate burglar James McCord, who alleged that perjury had been committed in the Watergate trial, and defendants had been pressured to remain silent. In an attempt to make them talk, Sirica gave Hunt and two burglars provisional sentences of up to 40 years.

Urged by Nixon, on March 28, aide John Ehrlichman told Attorney General Richard Kleindienst that nobody in the White House had had prior knowledge of the burglary. On April 13, Magruder told U.S. attorneys that he had perjured himself during the burglars' trial, and implicated John Dean and John Mitchell.[22]

John Dean believed that he, Mitchell, Ehrlichman, and Haldeman could go to the prosecutors, tell the truth, and save the presidency. Dean wanted to protect the president and have his four closest men take the fall for telling the truth. During the critical meeting between Dean and Nixon on April 15, 1973, Dean was totally unaware of the president's depth of knowledge and involvement in the Watergate cover-up. It was during this meeting that Dean felt that he was being recorded. He wondered if this was due to the way Nixon was speaking, as if he were trying to prod attendees' recollections of earlier conversations about fundraising. Dean mentioned this observation while testifying to the Senate Committee on Watergate, exposing the thread of what were taped conversations that would unravel the fabric of the conspiracy.[54]

Two days later, Dean told Nixon that he had been cooperating with the U.S. attorneys. On that same day, U.S. attorneys told Nixon that Haldeman, Ehrlichman, Dean, and other White House officials were implicated in the cover-up.[22][55][56]

On April 30, Nixon asked for the resignation of Haldeman and Ehrlichman, two of his most influential aides. They were both later indicted, convicted, and ultimately sentenced to prison. He asked for the resignation of Attorney General Kleindienst, to ensure no one could claim that his innocent friendship with Haldeman and Ehrlichman could be construed as a conflict. He fired White House Counsel John Dean, who went on to testify before the Senate Watergate Committee and said that he believed and suspected the conversations in the Oval Office were being taped. This information became the bombshell that helped force Richard Nixon to resign rather than be impeached.[57]

Writing from prison for New West and New York magazines in 1977, Ehrlichman claimed Nixon had offered him a large sum of money, which he declined.[58]

The President announced the resignations in an address to the American people:

In one of the most difficult decisions of my Presidency, I accepted the resignations of two of my closest associates in the White House, Bob Haldeman, John Ehrlichman, two of the finest public servants it has been my privilege to know. Because Attorney General Kleindienst, though a distinguished public servant, my personal friend for 20 years, with no personal involvement whatsoever in this matter has been a close personal and professional associate of some of those who are involved in this case, he and I both felt that it was also necessary to name a new Attorney General. The Counsel to the President, John Dean, has also resigned.[59]

On the same day, April 30, Nixon appointed a new attorney general, Elliot Richardson, and gave him authority to designate a special counsel for the Watergate investigation who would be independent of the regular Justice Department hierarchy. In May 1973, Richardson named Archibald Cox to the position.[22]

Senate Watergate hearings and revelation of the Watergate tapes

[edit]

On February 7, 1973, the United States Senate voted 77-to-0 to approve 93 Template:USBill and establish a select committee to investigate Watergate, with Sam Ervin named chairman the next day.[22] The hearings held by the Senate committee, in which Dean and other former administration officials testified, were broadcast from May 17 to August 7. The three major networks of the time agreed to take turns covering the hearings live, each network thus maintaining coverage of the hearings every third day, starting with ABC on May 17 and ending with NBC on August 7. An estimated 85% of Americans with television sets tuned into at least one portion of the hearings.[60]

On Friday, July 13, during a preliminary interview, deputy minority counsel Donald Sanders asked White House assistant Alexander Butterfield if there was any type of recording system in the White House.[61] Butterfield said he was reluctant to answer, but finally admitted there was a new system in the White House that automatically recorded everything in the Oval Office, the Cabinet Room and others, as well as Nixon's private office in the Old Executive Office Building.

On Monday, July 16, in front of a live, televised audience, chief minority counsel Fred Thompson asked Butterfield whether he was "aware of the installation of any listening devices in the Oval Office of the president". Butterfield's revelation of the taping system transformed the Watergate investigation. Cox immediately subpoenaed the tapes, as did the Senate, but Nixon refused to release them, citing his executive privilege as president, and ordered Cox to drop his subpoena. Cox refused.[62]

Saturday Night Massacre

[edit]On October 20, 1973, after Cox refused to drop the subpoena, Nixon ordered Attorney General Elliot Richardson to fire the special prosecutor. Richardson resigned in protest rather than carry out the order. Nixon then ordered Deputy Attorney General William Ruckelshaus to fire Cox, but Ruckelshaus also resigned rather than fire him. Nixon's search for someone in the Justice Department willing to fire Cox ended with Solicitor General Robert Bork. Though Bork said he believed Nixon's order was valid and appropriate, he considered resigning to avoid being "perceived as a man who did the President's bidding to save my job".[63] Bork carried out the presidential order and dismissed the special prosecutor.

These actions met considerable public criticism. Responding to the allegations of possible wrongdoing, in front of 400 Associated Press managing editors at Disney's Contemporary Resort,[64][65] on November 17, 1973, Nixon emphatically stated, "Well, I am not a crook."[66][67] He needed to allow Bork to appoint a new special prosecutor; Bork, with Nixon's approval, chose Leon Jaworski to continue the investigation.[68]

Legal action against Nixon Administration members

[edit]On March 1, 1974, a grand jury in Washington, D.C., indicted several former aides of Nixon, who became known as the "Watergate Seven"—H. R. Haldeman, John Ehrlichman, John N. Mitchell, Charles Colson, Gordon C. Strachan, Robert Mardian, and Kenneth Parkinson—for conspiring to hinder the Watergate investigation. The grand jury secretly named Nixon as an unindicted co-conspirator. The special prosecutor dissuaded them from an indictment of Nixon, arguing that a president can be indicted only after he leaves office.[69] John Dean, Jeb Stuart Magruder, and other figures had already pleaded guilty. On April 5, 1974, Dwight Chapin, the former Nixon appointments secretary, was convicted of lying to the grand jury. Two days later, the same grand jury indicted Ed Reinecke, the Republican Lieutenant Governor of California, on three charges of perjury before the Senate committee.

Release of the transcripts

[edit]

The Nixon administration struggled to decide what materials to release. All parties involved agreed that all pertinent information should be released. Whether to release unedited profanity and vulgarity divided his advisers. His legal team favored releasing the tapes unedited, while Press Secretary Ron Ziegler preferred using an edited version where "expletive deleted" would replace the raw material. After several weeks of debate, they decided to release an edited version. Nixon announced the release of the transcripts in a speech to the nation on April 29, 1974. Nixon noted that any audio pertinent to national security information could be redacted from the released tapes.[70]

Initially, Nixon gained a positive reaction for his speech. As people read the transcripts over the next couple of weeks, however, former supporters among the public, media and political community called for Nixon's resignation or impeachment. Vice President Gerald Ford said, "While it may be easy to delete characterization from the printed page, we cannot delete characterization from people's minds with a wave of the hand."[71] The Senate Republican Leader Hugh Scott said the transcripts revealed a "deplorable, disgusting, shabby, and immoral" performance on the part of the President and his former aides.[72] The House Republican Leader John Jacob Rhodes agreed with Scott, and Rhodes recommended that if Nixon's position continued to deteriorate, he "ought to consider resigning as a possible option".[73]

The editors of The Chicago Tribune, a newspaper that had supported Nixon, wrote, "He is humorless to the point of being inhumane. He is devious. He is vacillating. He is profane. He is willing to be led. He displays dismaying gaps in knowledge. He is suspicious of his staff. His loyalty is minimal."[74] The Providence Journal wrote, "Reading the transcripts is an emetic experience; one comes away feeling unclean."[75] This newspaper continued that, while the transcripts may not have revealed an indictable offense, they showed Nixon contemptuous of the United States, its institutions, and its people. According to Time magazine, the Republican Party leaders in the Western U.S. felt that while there remained a significant number of Nixon loyalists in the party, the majority believed that Nixon should step down as quickly as possible. They were disturbed by the bad language and the coarse, vindictive tone of the conversations in the transcripts.[75][76]

Supreme Court

[edit]The issue of access to the tapes went to the United States Supreme Court. On July 24, 1974, in United States v. Nixon, the Court ruled unanimously (8–0) that claims of executive privilege over the tapes were void. (Then-Justice William Rehnquist—who had recently been appointed to the Court by Nixon and most recently served in the Nixon Justice Department as Assistant Attorney General of the Office of Legal Counsel—recused himself from the case.) The Court ordered the President to release the tapes to the special prosecutor. On July 30, 1974, Nixon complied with the order and released the subpoenaed tapes to the public.

Release of the tapes

[edit]The tapes revealed several crucial conversations[77] that took place between the president and his counsel, John Dean, on March 21, 1973. In this conversation, Dean summarized many aspects of the Watergate case, and focused on the subsequent cover-up, describing it as a "cancer on the presidency". The burglary team was being paid hush money for their silence and Dean stated: "That's the most troublesome post-thing, because Bob [Haldeman] is involved in that; John [Ehrlichman] is involved in that; I am involved in that; Mitchell is involved in that. And that's an obstruction of justice." Dean continued, saying that Howard Hunt was blackmailing the White House demanding money immediately. Nixon replied that the money should be paid: "... just looking at the immediate problem, don't you have to have—handle Hunt's financial situation damn soon? ... you've got to keep the cap on the bottle that much, in order to have any options".[78]

At the time of the initial congressional proceedings, it was not known if Nixon had known and approved of the payments to the Watergate defendants earlier than this conversation. Nixon's conversation with Haldeman on August 1, is one of several that establishes he did. Nixon said: "Well ... they have to be paid. That's all there is to that. They have to be paid."[79] During the congressional debate on impeachment, some believed that impeachment required a criminally indictable offense. Nixon's agreement to make the blackmail payments was regarded as an affirmative act to obstruct justice.[71]

On December 7, investigators found that an 18½-minute portion of one recorded tape had been erased. Rose Mary Woods, Nixon's longtime personal secretary, said she had accidentally erased the tape by pushing the wrong pedal on her tape player when answering the phone. The press ran photos of the set-up, showing that it was unlikely for Woods to answer the phone while keeping her foot on the pedal. Later forensic analysis in 2003 determined that the tape had been erased in several segments—at least five, and perhaps as many as nine.[80]

Final investigations and resignation

[edit]- REDIRECT টেমপ্লেট:শুনুন

Nixon's position was becoming increasingly precarious. On February 6, 1974, the House of Representatives approved Template:USBill giving the Judiciary Committee authority to investigate impeachment of the President.[81][82] On July 27, 1974, the House Judiciary Committee voted 27-to-11 to recommend the first article of impeachment against the president: obstruction of justice. The Committee recommended the second article, abuse of power, on July 29, 1974. The next day, on July 30, 1974, the Committee recommended the third article: contempt of Congress. On August 20, 1974, the House authorized the printing of the Committee report H. Rep. 93–1305, which included the text of the resolution impeaching Nixon and set forth articles of impeachment against him.[83][84]

"Smoking Gun" tape

[edit]On August 5, 1974, the White House released a previously unknown audio tape from June 23, 1972. Recorded only a few days after the break-in, it documented the initial stages of the cover-up: it revealed Nixon and Haldeman had a meeting in the Oval Office during which they discussed how to stop the FBI from continuing its investigation of the break-in, as they recognized that there was a high risk that their position in the scandal might be revealed.

Haldeman introduced the topic as follows:

... the Democratic break-in thing, we're back to the—in the, the problem area because the FBI is not under control, because Gray doesn't exactly know how to control them, and they have ... their investigation is now leading into some productive areas ... and it goes in some directions we don't want it to go.[85]

After explaining how the money from CRP was traced to the burglars, Haldeman explained to Nixon the cover-up plan: "the way to handle this now is for us to have Walters [CIA] call Pat Gray [FBI] and just say, 'Stay the hell out of this ... this is ah, business here we don't want you to go any further on it.'"[85]

Nixon approved the plan, and after he was given more information about the involvement of his campaign in the break-in, he told Haldeman: "All right, fine, I understand it all. We won't second-guess Mitchell and the rest." Returning to the use of the CIA to obstruct the FBI, he instructed Haldeman: "You call them in. Good. Good deal. Play it tough. That's the way they play it and that's the way we are going to play it."[85][86]

Nixon denied that this constituted an obstruction of justice, as his instructions ultimately resulted in the CIA truthfully reporting to the FBI that there were no national security issues. Nixon urged the FBI to press forward with the investigation when they expressed concern about interference.[87]

Before the release of this tape, Nixon had denied any involvement in the scandal. He claimed that there were no political motivations in his instructions to the CIA, and claimed he had no knowledge before March 21, 1973, of involvement by senior campaign officials such as John Mitchell. The contents of this tape persuaded Nixon's own lawyers, Fred Buzhardt and James St. Clair, that "the President had lied to the nation, to his closest aides, and to his own lawyers—for more than two years".[88] The tape, which Barber Conable referred to as a "smoking gun", proved that Nixon had been involved in the cover-up from the beginning.

In the week before Nixon's resignation, Ehrlichman and Haldeman tried unsuccessfully to get Nixon to grant them pardons—which he had promised them before their April 1973 resignations.[89]

Resignation

[edit]

The release of the smoking gun tape destroyed Nixon politically. The ten congressmen who had voted against all three articles of impeachment in the House Judiciary Committee announced they would support the impeachment article accusing Nixon of obstructing justice when the articles came up before the full House.[90] Additionally, John Jacob Rhodes, the House leader of Nixon's party, announced that he would vote to impeach, stating that "coverup of criminal activity and misuse of federal agencies can neither be condoned nor tolerated".[91]

On the night of August 7, 1974, Senators Barry Goldwater and Hugh Scott and Congressman Rhodes met with Nixon in the Oval Office. Scott and Rhodes were the Republican leaders in the Senate and House, respectively; Goldwater was brought along as an elder statesman. The three lawmakers told Nixon that his support in Congress had all but disappeared. Rhodes told Nixon that he would face certain impeachment when the articles came up for vote in the full House; indeed, by one estimate, no more than 75 representatives were willing to vote against impeaching Nixon for obstructing justice.[91] Goldwater and Scott told the president that there were enough votes in the Senate to convict him, and that no more than 15 Senators were willing to vote for acquittal–not even half of the 34 votes he needed to stay in office.

Faced with the inevitability of his impeachment and removal from office and with public opinion having turned decisively against him, Nixon decided to resign.[92] In a nationally televised address from the Oval Office on the evening of August 8, 1974, the president said, in part:

In all the decisions I have made in my public life, I have always tried to do what was best for the Nation. Throughout the long and difficult period of Watergate, I have felt it was my duty to persevere, to make every possible effort to complete the term of office to which you elected me. In the past few days, however, it has become evident to me that I no longer have a strong enough political base in the Congress to justify continuing that effort. As long as there was such a base, I felt strongly that it was necessary to see the constitutional process through to its conclusion, that to do otherwise would be unfaithful to the spirit of that deliberately difficult process and a dangerously destabilizing precedent for the future.

... I would have preferred to carry through to the finish whatever the personal agony it would have involved, and my family unanimously urged me to do so. But the interest of the Nation must always come before any personal considerations. From the discussions I have had with Congressional and other leaders, I have concluded that because of the Watergate matter I might not have the support of the Congress that I would consider necessary to back the very difficult decisions and carry out the duties of this office in the way the interests of the Nation would require.

... I have never been a quitter. To leave office before my term is completed is abhorrent to every instinct in my body. But as President, I must put the interest of America first. America needs a full-time President and a full-time Congress, particularly at this time with problems we face at home and abroad. To continue to fight through the months ahead for my personal vindication would almost totally absorb the time and attention of both the President and the Congress in a period when our entire focus should be on the great issues of peace abroad and prosperity without inflation at home. Therefore, I shall resign the Presidency effective at noon tomorrow. Vice President Ford will be sworn in as President at that hour in this office.[93]

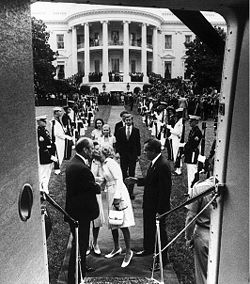

The morning that his resignation took effect, the President, with Mrs. Nixon and their family, said farewell to the White House staff in the East Room.[94] A helicopter carried them from the White House to Andrews Air Force Base in Maryland. Nixon later wrote that he thought, "As the helicopter moved on to Andrews, I found myself thinking not of the past, but of the future. What could I do now?" At Andrews, he and his family boarded an Air Force plane to El Toro Marine Corps Air Station in California, and then were transported to his home La Casa Pacifica in San Clemente.

President Ford's pardon of Nixon

[edit]

- 15px|link=|alt= Wikisource contiene obras originales de o sobre The Nixon Pardon.

With Nixon's resignation, Congress dropped its impeachment proceedings. Criminal prosecution was still a possibility at the federal level.[69] Nixon was succeeded by Vice President Gerald Ford as President, who on September 8, 1974, issued a full and unconditional pardon of Nixon, immunizing him from prosecution for any crimes he had "committed or may have committed or taken part in" as president.[95] In a televised broadcast to the nation, Ford explained that he felt the pardon was in the best interest of the country. He said that the Nixon family's situation "is an American tragedy in which we all have played a part. It could go on and on and on, or someone must write the end to it. I have concluded that only I can do that, and if I can, I must."[96]

Nixon continued to proclaim his innocence until his death in 1994. In his official response to the pardon, he said that he "was wrong in not acting more decisively and more forthrightly in dealing with Watergate, particularly when it reached the stage of judicial proceedings and grew from a political scandal into a national tragedy".[97]

Some commentators have argued that pardoning Nixon contributed to President Ford's loss of the presidential election of 1976.[98] Allegations of a secret deal made with Ford, promising a pardon in return for Nixon's resignation, led Ford to testify before the House Judiciary Committee on October 17, 1974.[99][100]

In his autobiography A Time to Heal, Ford wrote about a meeting he had with Nixon's Chief of Staff, Alexander Haig. Haig was explaining what he and Nixon's staff thought were Nixon's only options. He could try to ride out the impeachment and fight against conviction in the Senate all the way, or he could resign. His options for resigning were to delay his resignation until further along in the impeachment process, to try to settle for a censure vote in Congress, or to pardon himself and then resign. Haig told Ford that some of Nixon's staff suggested that Nixon could agree to resign in return for an agreement that Ford would pardon him.

Haig emphasized that these weren't his suggestions. He didn't identify the staff members and he made it very clear that he wasn't recommending any one option over another. What he wanted to know was whether or not my overall assessment of the situation agreed with his. [emphasis in original] ... Next he asked if I had any suggestions as to courses of actions for the President. I didn't think it would be proper for me to make any recommendations at all, and I told him so.

— Gerald Ford, A Time to Heal[101]

Aftermath

[edit]Final legal actions and effect on the law profession

[edit]Charles Colson pled guilty to charges concerning the Daniel Ellsberg case; in exchange, the indictment against him for covering up the activities of the Committee to Re-elect the President was dropped, as it was against Strachan. The remaining five members of the Watergate Seven indicted in March went on trial in October 1974. On January 1, 1975, all but Parkinson were found guilty. In 1976, the U.S. Court of Appeals ordered a new trial for Mardian; subsequently, all charges against him were dropped.

Haldeman, Ehrlichman, and Mitchell exhausted their appeals in 1977. Ehrlichman entered prison in 1976, followed by the other two in 1977. Since Nixon and many senior officials involved in Watergate were lawyers, the scandal severely tarnished the public image of the legal profession.[102][103][104]

The Watergate scandal resulted in 69 government officials being charged and 48 being found guilty, including:[14]

- John N. Mitchell, Attorney General of the United States who resigned to become Director of Committee to Re-elect the President, convicted of perjury about his involvement in the Watergate break-in. Served 19 months of a one- to four-year sentence.[23]

- Richard Kleindienst, Attorney General of the United States, convicted of "refusing to answer questions" (contempt of court); given one month in jail.[105]

- Jeb Stuart Magruder, Deputy Director of Committee to Re-elect the President,[27] pled guilty to one count of conspiracy to the burglary, and was sentenced to 10 months to four years in prison, of which he served seven months before being paroled.[106]

- Frederick C. LaRue, Advisor to John Mitchell, convicted of obstruction of justice. He served four and a half months.[106]

- H. R. Haldeman, White House Chief of Staff, convicted of conspiracy to the burglary, obstruction of justice, and perjury. Served 18 months in prison.[107]

- John Ehrlichman, White House Domestic Affairs Advisor, convicted of conspiracy to the burglary, obstruction of justice, and perjury. Served 18 months in prison.[108]

- Egil Krogh, United States Under Secretary of Transportation, sentenced to six months for his part in the Daniel Ellsberg case.[106]

- John W. Dean III, White House Counsel, convicted of obstruction of justice, later reduced to felony offenses and sentenced to time already served, which totaled four months.[106]

- Dwight L. Chapin, Secretary to the President of the United States, convicted of perjury.[106]

- Maurice Stans, United States Secretary of Commerce who resigned to become Finance Chairman of Committee to Re-elect the President, convicted of multiple counts of illegal campaigning, fined $5,000 (in 1975 – $20,400 today).[109]

- Herbert W. Kalmbach, personal attorney to Nixon, convicted of illegal campaigning. Served 191 days in prison and fined $10,000 (in 1974 – $44,500 today).[106]

- Charles W. Colson, Director of the Office of Public Liaison, convicted of obstruction of justice. Served seven months in Federal Maxwell Prison.[105]

- Herbert L. Porter, aide to the Committee to Re-elect the President. Convicted of perjury.[106]

- G. Gordon Liddy, Special Investigations Group, convicted of masterminding the burglary, original sentence of up to 20 years in prison.[106][110] Served 4 1⁄2 years in federal prison.[111]

- E. Howard Hunt, security consultant, convicted of masterminding and overseeing the burglary, original sentence of up to 35 years in prison.[106][110] Served 33 months in prison.[112]

- James W. McCord Jr., convicted of six charges of burglary, conspiracy and wiretapping.[106] Served two months in prison.[111]

- Virgilio Gonzalez, convicted of burglary, original sentence of up to 40 years in prison.[106][110] Served 13 months in prison.[111]

- Bernard Barker, convicted of burglary, original sentence of up to 40 years in prison.[106][110] Served 18 months in prison.[113]

- Eugenio Martínez, convicted of burglary, original sentence of up to 40 years in prison.[106][110] Served 15 months in prison.[114]

- Frank Sturgis, convicted of burglary, original sentence of up to 40 years in prison.[106][110] Served 10 months in prison.[114]

To defuse public demand for direct federal regulation of lawyers (as opposed to leaving it in the hands of state bar associations or courts), the American Bar Association (ABA) launched two major reforms. First, the ABA decided that its existing Model Code of Professional Responsibility (promulgated 1969) was a failure. In 1983, the ABA replaced the Model Code with the Model Rules of Professional Conduct.[115] The Model Rules have been adopted in part or in whole by all 50 states. The Model Rules's preamble contains an emphatic reminder that the legal profession can remain self-governing only if lawyers behave properly.[116] Second, the ABA promulgated a requirement that law students at ABA-approved law schools take a course in professional responsibility (which means they must study the Model Rules). The requirement remains in effect.[117]

On June 24 and 25, 1975, Nixon gave secret testimony to a grand jury. According to news reports at the time, Nixon answered questions about the 18 1⁄2-minute tape gap, altering White House tape transcripts turned over to the House Judiciary Committee, using the Internal Revenue Service to harass political enemies, and a $100,000 contribution from billionaire Howard Hughes. Aided by the Public Citizen Litigation Group, the historian Stanley Kutler, who has written several books about Nixon and Watergate and had successfully sued for the 1996 public release of the Nixon White House tapes,[118] sued for the release of the transcripts of the Nixon grand jury testimony.[119]

On July 29, 2011, U.S. District Judge Royce Lamberth granted Kutler's request, saying historical interests trumped privacy, especially considering that Nixon and other key figures were deceased, and most of the surviving figures had testified under oath, have been written about, or were interviewed. The transcripts were not immediately released pending the government's decision on whether to appeal.[119] They were released in their entirety on November 10, 2011, although the names of people still alive were redacted.[120]

Texas A&M University–Central Texas professor Luke Nichter wrote the chief judge of the federal court in Washington to release hundreds of pages of sealed records of the Watergate Seven. In June 2012 the U.S. Department of Justice wrote the court that it would not object to their release with some exceptions.[121] On November 2, 2012, Watergate trial records for G. Gordon Liddy and James McCord were ordered unsealed by Federal Judge Royce Lamberth.[122]

Political and cultural reverberations

[edit]According to Thomas J. Johnson, a professor of journalism at University of Texas at Austin, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger predicted during Nixon's final days that history would remember Nixon as a great president and that Watergate would be relegated to a "minor footnote".[123]

When Congress investigated the scope of the president's legal powers, it belatedly found that consecutive presidential administrations had declared the United States to be in a continuous open-ended state of emergency since 1950. Congress enacted the National Emergencies Act in 1976 to regulate such declarations. The Watergate scandal left such an impression on the national and international consciousness that many scandals since then have been labeled with the "-gate suffix".

Disgust with the revelations about Watergate, the Republican Party, and Nixon strongly affected results of the November 1974 Senate and House elections, which took place three months after Nixon's resignation. The Democrats gained five seats in the Senate and forty-nine in the House (the newcomers were nicknamed "Watergate Babies"). Congress passed legislation that changed campaign financing, to amend the Freedom of Information Act, as well as to require financial disclosures by key government officials (via the Ethics in Government Act). Other types of disclosures, such as releasing recent income tax forms, became expected, though not legally required. Presidents since Franklin D. Roosevelt had recorded many of their conversations but the practice purportedly ended after Watergate.

Ford's pardon of Nixon played a major role in his defeat in the 1976 presidential election against Jimmy Carter.[98]

In 1977, Nixon arranged an interview with British journalist David Frost in the hope of improving his legacy. Based on a previous interview in 1968,[124] he believed that Frost would be an easy interviewer and was taken aback by Frost's incisive questions. The interview displayed the entire scandal to the American people, and Nixon formally apologized, but his legacy remained tarnished.[125] The 2008 movie Frost/Nixon is a media depiction of this.

In the aftermath of Watergate, "follow the money" became part of the American lexicon and is widely believed to have been uttered by Mark Felt to Woodward and Bernstein. The phrase was never used in the 1974 book All the President's Men and did not become associated with it until the movie of the same name was released in 1976.[126] The 2017 movie Mark Felt: The Man Who Brought Down the White House is about Felt's role in the Watergate scandal and his identity as Deep Throat.

The parking garage where Woodward and Felt met in Rosslyn still stands. Its significance was noted by Arlington County with a historical marker in 2011.[127][128] In 2017 it was announced that the garage would be demolished as part of construction of an apartment building on the site; the developers announced that the site's significance would be memorialized within the new complex.[129][130]

Purpose of the break-in

[edit]Despite the enormous impact of the Watergate scandal, the purpose of the break-in of the DNC offices has never been conclusively established. Records from the United States v. Liddy trial, made public in 2013, showed that four of the five burglars testified that they were told the campaign operation hoped to find evidence that linked Cuban funding to Democratic campaigns.[131] The longtime hypothesis suggests that the target of the break-in was the offices of Larry O'Brien, the DNC chairman.[citation needed][132] However, O'Brien's name was not on Alfred C. Baldwin III's list of targets that was released in 2013.[citation needed] Among those listed were senior DNC official R. Spencer Oliver, Oliver's secretary Ida "Maxine" Wells, co-worker Robert Allen and secretary Barbara Kennedy.[131]

Based on these revelations, Texas A&M history professor Luke Nichter, who had successfully petitioned for the release of the information,[133] argued that Woodward and Bernstein were incorrect in concluding, based largely on Watergate burglar James McCord's word, that the purpose of the break-in was to bug O'Brien's phone to gather political and financial intelligence on the Democrats.[citation needed] Instead, Nichter sided with late journalist J. Anthony Lukas of The New York Times, who had concluded that the committee was seeking to find evidence linking the Democrats to prostitution, as it was alleged that Oliver's office had been used to arrange such meetings. However, Nichter acknowledged that Woodward and Bernstein's theory of O'Brien as the target could not be debunked unless the information was released about what Baldwin heard in his bugging of conversations.[citation needed]

In 1968, O'Brien was appointed by Vice President Hubert Humphrey to serve as the national director of Humphrey's presidential campaign and, separately, by Howard Hughes to serve as Hughes' public-policy lobbyist in Washington. O'Brien was elected national chairman of the DNC in 1968 and 1970. In late 1971, the president's brother, Donald Nixon, was collecting intelligence for his brother at the time and asked John H. Meier, an adviser to Howard Hughes, about O'Brien. In 1956, Donald Nixon had borrowed $205,000 from Howard Hughes and had never repaid the loan. The loan's existence surfaced during the 1960 presidential election campaign, embarrassing Richard Nixon and becoming a political liability. According to author Donald M. Bartlett, Richard Nixon would do whatever was necessary to prevent another family embarrassment.[134] From 1968 to 1970, Hughes withdrew nearly half a million dollars from the Texas National Bank of Commerce for contributions to both Democrats and Republicans, including presidential candidates Humphrey and Nixon. Hughes wanted Donald Nixon and Meier involved but Nixon opposed this.[135]

Meier told Donald Nixon that he was sure the Democrats would win the election because they had considerable information on Richard Nixon's illicit dealings with Hughes that had never been released, and that it resided with Larry O'Brien.[136] According to Fred Emery, O'Brien had been a lobbyist for Hughes in a Democrat-controlled Congress, and the possibility of his finding out about Hughes' illegal contributions to the Nixon campaign was too much of a danger for Nixon to ignore.[137]

James F. Neal, who prosecuted the Watergate 7, did not believe Nixon had ordered the break-in because of Nixon's surprised reaction when he was told about it.[138]

Reactions

[edit]Australia

[edit]Australian Prime Minister Gough Whitlam referred to the American presidency's "parlous position" without the direct wording of the Watergate scandal during Question Time in May 1973.[139] The following day responding to a question upon "the vital importance of future United States–Australia relations", Whitlam parried that the usage of the word 'Watergate' was not his.[140] United States–Australia relations have been considered to have figured as influential when, in November 1975, Australia experienced its own constitutional crisis which led to the dismissal of the Whitlam Government by Sir John Kerr, the Australian Governor-General.[141] Max Suich has suggested that the US was involved in ending the Whitlam government.[142]

China

[edit]Chinese then-Premier Zhou Enlai said in October 1973 that the scandal did not affect the relations between China and the United States.[143] According to the then–Prime Minister Kukrit Pramoj of Thailand in July 1975, Chairman Mao Zedong called the Watergate scandal "the result of 'too much freedom of political expression in the U.S.'"[144] Mao called it "an indication of American isolationism, which he saw as 'disastrous' for Europe". He further said, "Do Americans really want to go isolationist? ... In the two world wars, the Americans came [in] very late, but all the same, they did come in. They haven't been isolationist in practice."[145]

Japan

[edit]In August 1973, then–Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka said that the scandal had "no cancelling influence on U.S. leadership in the world". Tanaka further said, "The pivotal role of the United States has not changed, so this internal affair will not be permitted to have an effect."[146] In March 1975, Tanaka's successor, Takeo Miki, said at a convention of the Liberal Democratic Party, "At the time of the Watergate issue in America, I was deeply moved by the scene in the House Judiciary Committee, where each member of the committee expressed his own or her own heart based upon the spirit of the American Constitution. It was this attitude, I think, that rescued American democracy."[147]

Singapore

[edit]Then–Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew said in August 1973, "As one surprising revelation follows another at the Senate hearings on Watergate, it becomes increasingly clear that the District of Columbia (Washington D.C.), today is in no position to offer the moral or strong political and economic leadership for which its friends and allies are yearning."[148] Moreover, Lee said that the scandal may have led the United States to lessen its interests and commitments in world affairs, to weaken its ability to enforce the Paris Peace Accords on Vietnam, and to not react to violations of the Accords. Lee said further that the United States "makes the future of this peace in Indonesia an extremely bleak one with grave consequence for the contiguous states". Lee then blamed the scandal for economic inflation in Singapore because the Singapore dollar was pegged to the United States dollar at the time, assuming the U.S. dollar was stronger than the British pound sterling.[149]

Soviet Union

[edit]In June 1973, when chairman Leonid Brezhnev arrived in the United States to have a one-week meeting with Nixon,[150] Brezhnev told the press, "I do not intend to refer to that matter—[the Watergate]. It would be completely indecent for me to refer to it ... My attitude toward Mr. Nixon is of very great respect." When one reporter suggested that Nixon and his position with Brezhnev were "weakened" by the scandal, Brezhnev replied, "It does not enter my mind to think whether Mr. Nixon has lost or gained any influence because of the affair." Then he said further that he had respected Nixon because of Nixon's "realistic and constructive approach to Soviet Union–United States relations ... passing from an era of confrontation to an era of negotiations between nations".[151]

United Kingdom

[edit]Talks between Nixon and Prime Minister Edward Heath may have been bugged. Heath did not publicly display his anger, with aides saying that he was unconcerned about having been bugged at the White House. According to officials, Heath commonly had notes taken of his public discussions with Nixon so a recording would not have bothered him. However, officials privately said that if private talks with Nixon were bugged, then Heath would be outraged. Even so, Heath was privately outraged over being taped without his prior knowledge.[152]

Iran

[edit]Iranian then-Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi told the press in 1973, "I want to say quite emphatically ... that everything that would weaken or jeopardize the President's power to make decisions in split seconds would represent grave danger for the whole world."[146]

Kenya

[edit]An unnamed Kenyan senior official of Foreign Affairs Ministry accused Nixon of lacking interest in Africa and its politics and then said, "American President is so enmeshed in domestic problems created by Watergate that foreign policy seems suddenly to have taken a back seat [sic]."[146]

Cuba

[edit]Cuban then-leader Fidel Castro said in his December 1974 interview that, of the crimes committed by the Cuban exiles, like killings, attacks on Cuban ports, and spying, the Watergate burglaries and wiretappings were "probably the least of [them]".[153]

United States

[edit]After the fall of Saigon ended the Vietnam War, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger said in May 1975 that, if the scandal had not caused Nixon to resign, and Congress had not overridden Nixon's veto of the War Powers Resolution, North Vietnam would not have captured South Vietnam.[154] Kissinger told the National Press Club in January 1977 that Nixon's presidential powers weakened during his tenure, thus (as rephrased by the media) "prevent[ing] the United States from exploiting the [scandal]".[155]

The publisher of The Sacramento Union, John P. McGoff, said in January 1975 that the media overemphasized the scandal, though he called it "an important issue", overshadowing more serious topics, like a declining economy and an energy crisis.[156]

See also

[edit]- List of American federal politicians convicted of crimes

- Second-term curse

- List of -gate scandals and controversies

References

[edit]- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Perry, James M. "Watergate Case Study". Class Syllabus for "Critical Issues in Journalism". Columbia School of Journalism, Columbia University. Archived from the original on July 15, 2019. Retrieved July 27, 2018.

- ^ Dickinson, William B.; Cross, Mercer; Polsky, Barry (1973). Watergate: chronology of a crisis. Vol. 1. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Quarterly Inc. pp. 8, 133, 140, 180, 188. ISBN 0-87187-059-2. OCLC 20974031.

- ^ Rybicki, Elizabeth; Greene, Michael (October 10, 2019). "The Impeachment Process in the House of Representatives". CRS Report for Congress. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress. pp. 5–7. R45769. Archived from the original on January 22, 2020. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- ^ "H.Res.74 – 93rd Congress, 1st Session". congress.gov. February 28, 1973. Archived from the original on December 30, 2019. Retrieved October 21, 2019.

- ^ "A burglary turns into a constitutional crisis". CNN. June 16, 2004. Archived from the original on November 26, 2020. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- ^ "Senate Hearings: Overview". fordlibrarymuseum.gov. Archived from the original on July 2, 2017. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- ^ "A burglary turns into a constitutional crisis". CNN. June 16, 2004. Archived from the original on November 30, 2020. Retrieved May 13, 2014.

- ^ "'Gavel-to-Gavel': The Watergate Scandal and Public Television". American Archive of Public Broadcasting. Retrieved November 10, 2019.

- ^ Manheim, Karl; Solum, Lawrence B. (Spring 1999). "Nixon Articles of Impeachment". Impeachment Seminar. Archived from the original on March 3, 2017.

- ^ "The Smoking Gun Tape" (Transcript of the recording of a meeting between President Nixon and H. R. Haldeman). Watergate.info website. June 23, 1972. Archived from the original on May 1, 2012. Retrieved January 17, 2007.

- ^ White, Theodore Harold (1975). Breach of Faith: The Fall of Richard Nixon. New York: Atheneum Publishers. p. 7. ISBN 0-689-10658-0. OCLC 1370091.

- ^ White (1975), Breach of Faith, p. 29. "And the most punishing blow of all was to come in late afternoon when the President received, in his Oval Office, the Congressional leaders of his party—Barry Goldwater, Hugh Scott and John Rhodes. The accounts of all three men agree. Goldwater averred that there were not more than fifteen votes left in support of him in the Senate."

- ^ Dash, Samuel (1976). Chief Counsel: Inside the Ervin Committee – The Untold Story of Watergate. New York: Random House. pp. 259–260. ISBN 0-394-40853-5. OCLC 2388043.

Soon Alexander Haig and James St. Clair learned of the existence of this tape and they were convinced that it would guarantee Nixon's impeachment in the House of Representatives and conviction in the Senate.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bill Marsh (October 30, 2005). "Ideas & Trends – When Criminal Charges Reach the White House". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 18, 2022. Retrieved September 30, 2014.

- ^ Ervin, Sam, et al., Final Report of the Watergate Committee].

- ^ Hamilton, Dagmar S. "The Nixon Impeachment and the Abuse of Presidential Power", In Watergate and Afterward: The Legacy of Richard M. Nixon. Leon Friedman and William F. Levantrosser, eds. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood Publishing Group, 1992. ISBN 0-313-27781-8

- ^ Smith, Ronald D. and Richter, William Lee. Fascinating People and Astounding Events From American History. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 1993. ISBN 0-87436-693-3

- ^ Lull, James and Hinerman, Stephen. Media Scandals: Morality and Desire in the Popular Culture Marketplace. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997. ISBN 0-231-11165-7

- ^ Trahair, R.C.S. From Aristotelian to Reaganomics: A Dictionary of Eponyms With Biographies in the Social Sciences. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood Publishing Group, 1994. ISBN 0-313-27961-6

- ^ "El 'valijagate' sigue dando disgustos a Cristina Fernández | Internacional". El País. November 4, 2008. Archived from the original on July 2, 2017. Retrieved July 28, 2014.

- ^ Dean, John W. (2014). The Nixon Defense: What He Knew and When He Knew It. Viking. p. xvii. ISBN 978-0-670-02536-7.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g "Watergate Retrospective: The Decline and Fall", Time, August 19, 1974

- ^ Jump up to: a b Meyer, Lawrence (November 10, 1988). "John N. Mitchell, Principal in Watergate, Dies at 75". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 30, 2008. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- ^ Rugaber, Walter (January 18, 1973). "Watergate Trial in Closed Session". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 24, 2018. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Alfred C. Baldwin". Spartacus Educational. Archived from the original on July 2, 2014. Retrieved April 4, 2021.

- ^ G Gordon Liddy ( 1980). Will, pp. 195, 226, 232, St. Martin's Press ISBN 978-0312880149

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Pear, Robert (June 14, 1992). "Watergate, Then and Now – 2 Decades After a Political Burglary, the Questions Still Linger". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 8, 2022. Retrieved May 18, 2015.

- ^ "Liddy Testifies in Watergate Trial". ABC News. Archived from the original on May 19, 2021. Retrieved May 22, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Brown, DeNeen (2017). "'The Post' and the forgotten security guard who discovered the Watergate break-in". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 24, 2019. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Shirley, Craig (June 20, 2012). "The Bartender's Tale: How the Watergate Burglars Got Caught | Washingtonian". Washingtonian. Archived from the original on June 7, 2022. Retrieved March 31, 2020.

- ^ Lewis, Alfred E. (June 18, 1972). "5 Held in Plot to Bug Democrats' Office Here". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 22, 2011. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- ^ Bug Suspect Got Campaign Funds Archived June 18, 2022, at the Wayback Machine The Washington Post

- ^ Genovese, Michael A. (1999). The Watergate Crisis. Westport, CN: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0313298783.

- ^ Dickinson, William B.; Mercer Cross; Barry Polsky (1973). Watergate: Chronology of a Crisis. Vol. 1. Washington D. C.: Congressional Quarterly Inc. p. 4. ISBN 0-87187-059-2. OCLC 20974031.

- ^ Sirica, John J. (1979). To Set the Record Straight: The Break-in, the Tapes, the Conspirators, the Pardon. New York: Norton. p. 44. ISBN 0-393-01234-4.

- ^ "Transcript of a Recording of a Meeting Between The President And H.R. Haldeman in the Oval Office On June 23, 1972 From 10:04 To 11:39 a.m." (PDF). Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 28, 2018. Retrieved September 10, 2018.

- ^ Brockell, Gillian. "'I'm a political prisoner': Mouthy Martha Mitchell was the George Conway of the Nixon era". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved November 17, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Cadden, Vivian (July 1973). "Martha Mitchell: the Day the Laughing Stopped" (PDF). The Harold Weisberg Archive. McCall's Magazine. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 22, 2020. Retrieved October 14, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Stein, Jeff (December 11, 2017). "Trump Ambassador Beat and 'Kidnapped' Woman in Watergate Cover-Up: Reports". Newsweek. Archived from the original on September 1, 2019. Retrieved September 12, 2019.

- ^ Reeves, Richard (2002). President Nixon : alone in the White House (1st Touchstone ed. 2002. ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 511. ISBN 0-7432-2719-0.

- ^ McLendon, Winzola (1979). Martha: The Life of Martha Mitchell. ISBN 9780394411248.

- ^ "McCord Declares That Mrs. Mitchell Was Forcibly Held". The New York Times. February 19, 1975. Archived from the original on October 20, 2020. Retrieved September 12, 2019.

- ^ "Brief Timeline of Events". Malcolm Farnsworth. Archived from the original on May 19, 2012. Retrieved May 24, 2012.

- ^ "John N. Mitchell Dies at 75; Major Figure in Watergate". The New York Times. November 10, 1988. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 15, 2021. Retrieved January 25, 2017.

- ^ Meyer, Lawrence (November 10, 1988). "John N. Mitchell, Principal in Watergate, Dies at 75". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 30, 2008. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- ^ Quote: "There were still simply too many unanswered questions in the case. By that time, thinking about the break-in and reading about it, I'd have had to be some kind of moron to believe that no other people were involved. No political campaign committee would turn over so much money to a man like Gordon Liddy without someone higher up in the organization approving the transaction. How could I not see that? These questions about the case were on my mind during a pretrial session in my courtroom on December 4." Sirica, John J. (1979). To Set the Record Straight: The Break-in, the Tapes, the Conspirators, the Pardon. New York: Norton. p. 56. ISBN 0-393-01234-4.

- ^ "Woodward Downplays Deep Throat" Archived June 19, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Politico. blog, June 2012. Retrieved February 8, 2015

- ^ "The profound lies of Deep Throat" Archived February 2, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, The Miami Herald, republished in Portland Press Herald, February 14, 2012

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Covering Watergate: Success and Backlash". Time. July 8, 1974. Archived from the original on June 2, 2013. Retrieved July 24, 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Crouse, Timothy (1973).The Boys on the Bus, Random House, p. 298

- ^ "The Nation: More Evidence: Huge Case for Judgment". Time. July 29, 1974. Archived from the original on May 21, 2013. Retrieved July 24, 2011.

- ^ "The Nixon Years: Down from the Mountaintop". Time. August 19, 1974. Archived from the original on May 21, 2013. Retrieved July 24, 2011.

- ^ Dean, John W. (2014). The Nixon Defense, p. 344, Penguin Group, ISBN 978-0-670-02536-7

- ^ Dean, John W. (2014). The Nixon Defense: What He Knew and When He Knew It, pp. 415–416, Penguin Group, ISBN 978-0-670-02536-7

- ^ "Watergate Scandal, 1973 In Review". United Press International. September 8, 1973. Archived from the original on July 22, 2010. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- ^ "When Judge Sirica finished reading the letter, the courtroom exploded with excitement and reporters ran to the rear entrance to phone their newspapers. The bailiff kept banging for silence. It was a stunning development, exactly what I had been waiting for. Perjury at the trial. The involvement of others. It looked as if Watergate was about to break wide open." Dash, Samuel (1976). Chief Counsel: Inside the Ervin Committee – The Untold Story of Watergate. New York: Random House. p. 30. ISBN 0-394-40853-5. OCLC 2388043.

- ^ Dean, John W. (2014). The Nixon Defense: What He Knew and When He Knew It, pp. 610–620, Penguin Group, ISBN 978-0-670-02536-7

- ^ "Sequels: Nixon: Once More, with Feeling", Time, May 16, 1977

- ^ "Watergate Scandal, 1973 in Review". United Press International. September 8, 1973. Archived from the original on July 22, 2010. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- ^ Garay, Ronald. "Watergate". The Museum of Broadcast Communication. Archived from the original on June 5, 2018. Retrieved January 17, 2007.

- ^ Kranish, Michael (July 4, 2007). "Select Chronology for Donald G. Sanders". Boston Globe. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- ^ "Watergate Scandal, 1973 In Review". United Press International. September 8, 1973. Archived from the original on July 22, 2010. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- ^ Noble, Kenneth (July 2, 1987). "Bork Irked by Emphasis on His Role in Watergate". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 1, 2018. Retrieved May 26, 2009.

- ^ Pope, Rich (October 31, 2016). "Nixon, Watergate and Walt Disney World? There is a connection". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on April 9, 2017. Retrieved April 8, 2017.

- ^ Apple, R.W. Jr. "Nixon Declares He Didn't Profit From Public Life". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 7, 2001. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- ^ "Question-and-Answer Session at the Annual Convention of the Associated Press Managing Editors Association, Orlando, Florida | The American Presidency Project". www.presidency.ucsb.edu. Archived from the original on July 16, 2019. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

Well, I am not a crook

- ^ Kilpatrick, Carroll (November 18, 1973). "Nixon Tells Editors, 'I'm Not a Crook". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 30, 2013. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- ^ Times, John Herbers Special to The New York (November 2, 1973). "Nixon Names Saxbe Attorney General; Jaworski Appointed Special Prosecutor". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 29, 2022. Retrieved December 29, 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Legal Aftermath Citizen Nixon and the Law". Time. August 19, 1974. Archived from the original on December 21, 2011. Retrieved July 24, 2011.

- ^ Theodore White. Breach of Faith: The Fall of Richard Nixon Archived April 27, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Reader's Digest Press, Athineum Publishers, 1975, pp. 296–298

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bernstein, C. and Woodward, B. (1976).The Final Days, p. 252. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- ^ "Obituary: Hugh Scott, A Dedicated Public Servant". The Morning Call. July 26, 1994. Archived from the original on December 11, 2015. Retrieved December 8, 2015.

- ^ "GOP Leaders Favour Stepdown". The Stanford Daily. Associated Press. May 10, 1974. Archived from the original on February 3, 2017. Retrieved December 8, 2015.

- ^ Patricia Sullivan (June 24, 2004). "Obituary: Clayton Kirkpatrick, 89; Chicago Tribune Editor". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 11, 2015. Retrieved December 8, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Time". Time. Vol. 103, no. 20. May 20, 1974. Archived from the original on January 4, 2010. Retrieved July 24, 2011.

- ^ "Time". Time. Vol. 103, no. 19. May 13, 1974. Archived from the original on January 17, 2010. Retrieved July 24, 2011.

- ^ Kutler, S. (1997). Abuse of Power, p. 247. Simon & Schuster.