This article needs to be updated. (April 2022) |

| |

Headquarters in Sunnyvale, California | |

| Web address | www |

|---|---|

| Registration | Required |

| Available in | Multilingual (24) |

| Users | |

| Launched | Template:MONTHNAME 5, 2003 |

| Revenue | |

| Current status | Active |

LinkedIn (/lɪŋktˈɪn/) is a business and employment-focused social media platform that works through websites and mobile apps. It launched on May 5, 2003.[2] It is now owned by Microsoft.[3] The platform is primarily used for professional networking and career development, and allows jobseekers to post their CVs and employers to post jobs. From 2015 most of the company's revenue came from selling access to information about its members to recruiters and sales professionals.[4] Since December 2016, it has been a wholly owned subsidiary of Microsoft. As of Template:MONTHNAME 2023,[update][[Category:Articles containing potentially dated statements from Expression error: Unexpected < operator.]] LinkedIn has more than 900 million registered members from over 200 countries and territories.[2]

LinkedIn allows members (both workers and employers) to create profiles and connect with each other in an online social network which may represent real-world professional relationships. Members can invite anyone (whether an existing member or not) to become a connection. LinkedIn can also be used to organize offline events, join groups, write articles, publish job postings, post photos and videos, and more.[5]

Company overview

[edit]Founded in Mountain View, California, LinkedIn is currently headquartered in Sunnyvale, California, with 33 global offices.[6] In May 2020, the company had around 20,500 employees.[7]

LinkedIn's CEO is Ryan Roslansky. Jeff Weiner, previously CEO of LinkedIn, is now the Executive Chairman. Reid Hoffman, founder of LinkedIn, is chairman of the board.[8][9] It was funded by Sequoia Capital, Greylock, Bain Capital Ventures,[10] Bessemer Venture Partners and the European Founders Fund.[11] LinkedIn reached profitability in March 2006.[12] Since January 2011 the company had received a total of $103 million of investment.[13]

According to a 2016 The New York Times article, US high school students were creating LinkedIn profiles to include with their college applications.[14][15] Based in the United States, the site is, as of 2013, available in 24 languages.[8][16][17] LinkedIn filed for an initial public offering in January 2011 and traded its first shares in May, under the NYSE symbol "LNKD".[18]

History

[edit]Founding from 2002 to 2011

[edit]

The company was founded in December 2002 by Reid Hoffman and the founding team members from PayPal and Socialnet.com (Allen Blue, Eric Ly, Jean-Luc Vaillant, Lee Hower, Konstantin Guericke, Stephen Beitzel, David Eves, Ian McNish, Yan Pujante, Chris Saccheri).[19] In late 2003, Sequoia Capital led the Series A investment in the company.[20] In August 2004, LinkedIn reached 1 million users.[21] In March 2006, LinkedIn achieved its first month of profitability.[21] In April 2007, LinkedIn reached 10 million users.[21] In February 2008, LinkedIn launched a mobile version of the site.[22]

In June 2008, Sequoia Capital, Greylock Partners, and other venture capital firms purchased a 5% stake in the company for $53 million, giving the company a post-money valuation of approximately $1 billion.[23] In November 2009, LinkedIn opened its office in Mumbai[24] and soon thereafter in Sydney, as it started its Asia-Pacific team expansion. In 2010 LinkedIn opened an International Headquarters in Dublin, Ireland,[25] received a $20 million investment from Tiger Global Management LLC at a valuation of approximately $2 billion,[26] announced its first acquisition, Mspoke,[27] and improved its 1% premium subscription ratio.[28] In October of that year, Silicon Valley Insider ranked the company No. 10 on its Top 100 List of most valuable startups.[29] By December, the company was valued at $1.575 billion in private markets.[30] LinkedIn started its India operations in 2009 and a major part of the first year was dedicated to understanding professionals in India and educating members to leverage LinkedIn for career development.

2011 to present

[edit]

LinkedIn filed for an initial public offering in January 2011. The company traded its first shares on May 19, 2011, under the NYSE symbol "LNKD", at $45 per share. Shares of LinkedIn rose as much as 171% on their first day of trade on the New York Stock Exchange and closed at $94.25, more than 109% above IPO price. Shortly after the IPO, the site's underlying infrastructure was revised to allow accelerated revision-release cycles.[8] In 2011 LinkedIn earned $154.6 million in advertising revenue alone, surpassing Twitter, which earned $139.5 million.[31] LinkedIn's fourth-quarter 2011, earnings soared because of the company's increase in success in the social media world.[32] By this point LinkedIn had about 2,100 full-time employees compared to the 500 that it had in 2010.[33]

In April 2014 LinkedIn announced that it had leased 222 Second Street, a 26-story building under construction in San Francisco's SoMa district, to accommodate up to 2,500 of its employees,[34] with the lease covering 10 years.[35] The goal was to join all San Francisco-based staff (1,250 as of January 2016) in one building, bringing sales and marketing employees together with the research and development team.[35] In March 2016 they started to move in.[35] In February 2016 following an earnings report, LinkedIn's shares dropped 43.6% within a single day, down to $108.38 per share. LinkedIn lost $10 billion of its market capitalization that day.[36][37]

In 2016 access to LinkedIn was blocked by Russian authorities for non-compliance with the 2015 national legislation that requires social media networks to store citizens' personal data on servers located in Russia.[38]

In June 2016, Microsoft announced that it would acquire LinkedIn for $196 a share, a total value of $26.2 billion, and the second largest acquisition made by Microsoft to date. The acquisition would be an all-cash, debt-financed transaction. Microsoft would allow LinkedIn to "retain its distinct brand, culture and independence", with Weiner to remain as CEO, who would then report to Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella. Analysts believed Microsoft saw the opportunity to integrate LinkedIn with its Office product suite to help better integrate the professional network system with its products. The deal was completed on December 8, 2016.[39]

In late 2016 LinkedIn announced a planned increase of 200 new positions in its Dublin office, which would bring the total employee count to 1,200.[40] Since 2017 94% of B2B marketers use LinkedIn to distribute content.[41]

Soon after LinkedIn's acquisition by Microsoft, LinkedIn's new desktop version was introduced.[42] The new version was meant to make the user experience seamless across mobile and desktop. Some changes were made according to the feedback received from the previously launched mobile app. Features that were not heavily used were removed. For example, the contact tagging and filtering features are not supported anymore.[43]

Following the launch of the new user interface (UI), some users complained about the missing features which were there in the older version, slowness, and bugs in it. The issues were faced by free and premium users and with both the desktop and mobile versions of the site.

In 2019 LinkedIn launched globally the feature Open for Business that enables freelancers to be discovered on the platform.[44][45] LinkedIn Events was launched in the same year.[46][47]

In June 2020 Jeff Weiner stepped down as CEO and become executive chairman after 11 years in the role. Ryan Roslansky stepped up as CEO from his previous position as the senior vice president of product.[48] In late July 2020, LinkedIn announced it laid off 960 employees, about 6 percent of total workforce, from the talent acquisition and global sales teams. In an email to all employees, CEO Ryan Roslansky said the cuts were due to effects of the global COVID-19 pandemic.[49] In April 2021 CyberNews claimed that 500 million LinkedIn's accounts have leaked online.[50] However, LinkedIn stated that "We have investigated an alleged set of LinkedIn data that has been posted for sale and have determined that it is actually an aggregation of data from a number of websites and companies".[51][52]

In June 2021 PrivacySharks claimed that more than 700 million LinkedIn records was on sale on a hacker forum.[53][54] LinkedIn later stated that this is not a breach, but scraped data which is also a violation of their Terms of Service.[55]

Microsoft ended LinkedIn operations in China in October 2021.[56]

In May 2023, LinkedIn cut 716 positions from its 20,000 workforce. The move, according to a letter from the company's CEO Ryan Roslansky, was made to streamline the business's operations. Roslansky further stated that this decision would result in the creation of 250 job opportunities. Additionally, LinkedIn also announced the discontinuance of its China local job apps.[57]

Acquisitions

[edit]In July 2012 LinkedIn acquired 15 key Digg patents for $4 million including a "click a button to vote up a story" patent.[58]

| Number | Acquisition date | Company | Business | Country | Price | Description | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | August 4, 2010 | mspoke | Adaptive personalization of content | Template:Country data USA | $0.6 million[59] | LinkedIn Recommendations | [60] |

| 2 | September 23, 2010 | ChoiceVendor | Social B2B Reviews | Template:Country data USA | $3.9 million[61] | Rate and review B2B service providers | [62] |

| 3 | January 26, 2011 | CardMunch | Social Contacts | Template:Country data USA | $1.7 million[59] | Scan and import business cards | [63] |

| 4 | October 5, 2011 | Connected | Social CRM | Template:Country data USA | - | LinkedIn Connected | [64] |

| 5 | October 11, 2011 | IndexTank | Social search | Template:Country data USA | - | LinkedIn Search | [65] |

| 6 | February 22, 2012 | Rapportive | Social Contacts | Template:Country data USA | $15 million[66] | - | [67] |

| 7 | May 3, 2012 | SlideShare | Social Content | Template:Country data USA | $119 million | Give LinkedIn members a way to discover people through content | [68] |

| 8 | April 11, 2013 | Pulse | Web / Mobile newsreader | Template:Country data USA | $90 million | Definitive professional publishing platform | [69] |

| 9 | February 6, 2014 | Bright.com | Job Matching | Template:Country data USA | $120 million | [70] | |

| 10 | July 14, 2014 | Newsle | Web application | Template:Country data USA | - | Allows users to follow real news about their Facebook friends, LinkedIn contacts, and public figures. | [71] |

| 11 | July 22, 2014 | Bizo | Web application | Template:Country data USA | $175 million | Helps advertisers reach businesses and professionals | [72] |

| 12 | March 16, 2015 | Careerify | Web application | - | Helps businesses hire people using social media | [73] | |

| 13 | April 2, 2015 | Refresh.io | Web application | Template:Country data USA | - | Surfaces insights about people in your networks right before you meet them | [74] |

| 14 | April 9, 2015 | Lynda.com | eLearning | Template:Country data USA | $1.5 billion | Lets users learn business, technology, software, and creative skills through videos | [75] |

| 15 | August 28, 2015 | Fliptop | Predictive Sales and Marketing Firm | Template:Country data USA | - | Using data science to help companies close more sales | [76] |

| 16 | February 4, 2016 | Connectifier | Web application | Template:Country data USA | - | Helps companies with their recruiting | [77] |

| 17 | July 26, 2016 | PointDrive | Web application | Template:Country data USA | - | Lets salespeople share visual content with prospective clients to help seal the deal | [78] |

| 18 | September 16, 2018 | Glint Inc. | Web application | Template:Country data USA | - | Employee engagement platform. | [79] |

| 19 | May 28, 2019 | Drawbridge | Marketing Solutions | Template:Country data USA | [80] |

Perkins lawsuit

[edit]In 2013 a class action lawsuit entitled Perkins vs. LinkedIn Corp was filed against the company, accusing it of automatically sending invitations to contacts in a member's email address book without permission. The court agreed with LinkedIn that permission had in fact been given for invitations to be sent, but not for the two further reminder emails.[81] LinkedIn settled the lawsuit in 2015 for $13 million.[82] Many members should have received a notice in their email with the subject line "Legal Notice of Settlement of Class Action". The Case No. is 13-CV-04303-LHK.[83]

hiQ Labs v. LinkedIn

[edit]In May 2017 LinkedIn sent a Cease-And-Desist letter to hiQ Labs, a Silicon Valley startup that collects data from public profiles and provides analysis of this data to its customers. The letter demanded that hiQ immediately cease "scraping" data from LinkedIn's servers, claiming violations of the CFAA (Computer Fraud and Abuse Act) and the DMCA (Digital Millennium Copyright Act). In response hiQ sued LinkedIn in the Northern District of California in San Francisco, asking the court to prohibit LinkedIn from blocking its access to public profiles while the court considered the merits of its request. The court served a preliminary injunction against LinkedIn, which was then forced to allow hiQ to continue to collect public data. LinkedIn appealed this ruling; in September 2019, the appeals court rejected LinkedIn's arguments and the preliminary injunction was upheld. The dispute is ongoing.

Membership

[edit]

As of 2015 LinkedIn had more than 400 million members in over 200 countries and territories.[8][84] It is significantly ahead of its competitors Viadeo (50 million as of 2013)[85] and XING (11 million as of 2016).[86] In 2011, its membership grew by approximately two new members every second.[87] In 2020 LinkedIn's membership grew to over 690 million LinkedIn members.[88] As of September 2021 LinkedIn has 774+ million registered members from over 200 countries and territories.[88]

Platform and features

[edit]User profile network

[edit]Basic functionality

[edit]The basic functionality of LinkedIn allows users to create profiles, which for employees typically consist of a curriculum vitae describing their work experience, education and training, skills, and a personal photo. Employers can list jobs and search for potential candidates. Users can find jobs, people and business opportunities recommended by someone in one's contact network. Users can save jobs that they would like to apply for. Users also have the ability to follow different companies.

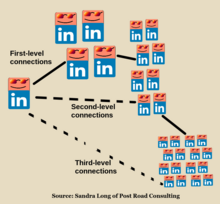

The site also enables members to make "connections" to each other in an online social network which may represent real-world professional relationships. Members can invite anyone to become a connection. Users can obtain introductions to the connections of connections (termed second-degree connections) and connections of second-degree connections (termed third-degree connections).

A member's list of connections can be used in a number of ways. For example, users can search for second-degree connections who work at a company they are interested in, and then ask a specific first-degree connection in common for an introduction.[89] The "gated-access approach" (where contact with any professional requires either an existing relationship, or the intervention of a contact of theirs) is intended to build trust among the service's users. LinkedIn participated in the EU's International Safe Harbor Privacy Principles.[90]

Users can interact with each other in a variety of ways:

- Connections can interact by choosing to "like" posts and "congratulate" others on updates such as birthdays, anniversaries and new positions, as well as by direct messaging.

- Users can share video with text and filters with the introduction of LinkedIn Video.[91][92]

- Users can write posts and articles[93] within the LinkedIn platform to share with their network.

Since September 2012 LinkedIn has enabled users to "endorse" each other's skills. However, there is no way of flagging anything other than positive content.[94] LinkedIn solicits endorsements using algorithms that generate skills members might have. Members cannot opt out of such solicitations, with the result that it sometimes appears that a member is soliciting an endorsement for a non-existent skill.[95]

Applications

[edit]LinkedIn 'applications' often refer to external third-party applications that interact with LinkedIn's developer API. However, in some cases, it could refer to sanctioned applications featured on a user's profile page.

External, third party applications

[edit]In February 2015 LinkedIn released an updated terms of use for their developer API.[96] The developer API allows both companies and individuals the ability to interact with LinkedIn's data through creation of managed third-party applications. Applications must go through a review process and request permission from the user before accessing a user's data.

Normal use of the API is outlined in LinkedIn's developer documents,[97] including:

- Sign into external services using LinkedIn

- Add items or attributes to a user profile

- Share items or articles to user's timeline

Embedded in profile

[edit]In October 2008, LinkedIn enabled an "applications platform" which allows external online services to be embedded within a member's profile page. Among the initial applications were an Amazon Reading List that allows LinkedIn members to display books they are reading, a connection to Tripit, and a Six Apart, WordPress and TypePad application that allows members to display their latest blog postings within their LinkedIn profile.[98] In November 2010, LinkedIn allowed businesses to list products and services on company profile pages; it also permitted LinkedIn members to "recommend" products and services and write reviews.[99] Shortly after, some of the external services were no longer supported, including Amazon's Reading List.[citation needed]

Mobile

[edit]A mobile version of the site was launched in February 2008 and made available in six languages: Chinese, English, French, German, Japanese and Spanish.[100] In January 2011, LinkedIn acquired CardMunch, a mobile app maker that scans business cards and converts into contacts.[101] In June 2013, CardMunch was noted as an available LinkedIn app.[8] In October 2013, LinkedIn announced a service for iPhone users called "Intro", which inserts a thumbnail of a person's LinkedIn profile in correspondence with that person when reading mail messages in the native iOS Mail program.[102] This is accomplished by re-routing all emails from and to the iPhone through LinkedIn servers, which security firm Bishop Fox asserts has serious privacy implications, violates many organizations' security policies, and resembles a man-in-the-middle attack.[103][104]

Groups

[edit]LinkedIn also supports daily the formation of interest groups. In 2012 there were 1,248,019 such groups whose membership varies from 1 to 744,662.[105][106] Groups support a limited form of discussion area, moderated by the group owners and managers.[107] Groups may be private, accessible to members only or may be open to Internet users in general to read, though they must join in order to post messages. Since groups offer the functionality to reach a wide audience without so easily falling foul of anti-spam solutions, there is a constant stream of spam postings, and there now exists a range of firms who offer a spamming service for this very purpose. LinkedIn has devised a few mechanisms to reduce the volume of spam,[108] but recently[when?] took the decision to remove the ability of group owners to inspect the email address of new members in order to determine if they were spammers.[citation needed] Groups also keep their members informed through emails with updates to the group, including most talked about discussions within your professional circles.[105][109]

In December 2011 LinkedIn announced that they are rolling out polls to groups.[110] In November 2013, LinkedIn announced the addition of Showcase Pages to the platform.[111] In 2014, LinkedIn announced they were going to be removing Product and Services Pages[112] paving the way for a greater focus on Showcase Pages.[113]

Knowledge graph

[edit]LinkedIn maintains an internal knowledge graph of entities (people, organizations, groups) that helps it connect everyone working in a field or at an organization or network. This can be used to query the neighborhood around each entity to find updates that might be related to it.[114] This also lets them train machine learning models that can infer new properties about an entity, or new information that may apply to it, for both summary views and for analytics.[115]

Discontinued features

[edit]In January 2013 LinkedIn dropped support for LinkedIn Answers and cited a new 'focus on development of new and more engaging ways to share and discuss professional topics across LinkedIn' as the reason for the retirement of the feature. The feature had been launched in 2007 and allowed users to post questions to their network and allowed users to rank answers.

In 2014 LinkedIn retired InMaps, a feature which allowed you to visualize your professional network.[116] The feature had been in use since January 2011.

According to the company's website, LinkedIn Referrals will no longer be available after May 2018.[117][needs update]

In September 2021 LinkedIn discontinued LinkedIn stories, a feature that was rolled out worldwide in October 2020.[118]

Usage

[edit]Personal branding

[edit]

LinkedIn is particularly well-suited for personal branding which, according to Sandra Long, entails "actively managing one's image and unique value" to position oneself for career opportunities.[119] LinkedIn has evolved from being a mere platform for job searchers into a social network which allows users a chance to create a personal brand.[120] Career coach Pamela Green describes a personal brand as the "emotional experience you want people to have as a result of interacting with you," and a LinkedIn profile is an aspect of that.[121] A contrasting report suggests that a personal brand is "a public-facing persona, exhibited on LinkedIn, Twitter and other networks, that showcases expertise and fosters new connections."[122]

LinkedIn allows professionals to build exposure for their personal brand within the site itself as well as in the World Wide Web as a whole. With a tool that LinkedIn dubs a Profile Strength Meter, the site encourages users to offer enough information in their profile to optimize visibility by search engines. It can strengthen a user's LinkedIn presence if he or she belongs to professional groups in the site.[123][119] The site enables users to add video to their profiles.[124] Some users hire a professional photographer for their profile photo.[125] Video presentations can be added to one's profile.[126] LinkedIn's capabilities have been expanding so rapidly that a cottage industry of outside consultants has grown up to help users navigate the system.[127][124][128] A particular emphasis is helping users with their LinkedIn profiles.[127]

There's no hiding in the long grass on LinkedIn ... The number one mistake people make on the profile is to not have a photo.

— Sandra Long of Post Road Consulting, 2017[129]

In October 2012, LinkedIn launched the LinkedIn Influencers program, which features global thought leaders who share their professional insights with LinkedIn's members. As of May 2016, there are 750+ Influencers.[130] The program is invite-only and features leaders from a range of industries including Richard Branson, Narendra Modi, Arianna Huffington, Greg McKeown, Rahm Emanuel, Jamie Dimon, Martha Stewart, Deepak Chopra, Jack Welch, and Bill Gates.[131][132]

Job seeking

[edit]LinkedIn is widely used by job seekers and employers. According to Jack Meyer the site has become the "premier digital platform" for professionals to network online.[123] In Australia, which has approximately twelve million working professionals, ten million of them are on LinkedIn, according to Anastasia Santoreneos, suggesting that the probability was high that one's "future employer is probably on the site."[133] According to one estimate based on worldwide figures, 122 million users got job interviews via LinkedIn and 35 million were hired by a LinkedIn online connection.[134]

LinkedIn also allows users to research companies, non-profit organizations, and governments they may be interested in working for. Typing the name of a company or organization in the search box causes pop-up data about the company or organization to appear. Such data may include the ratio of female to male employees, the percentage of the most common titles/positions held within the company, the location of the company's headquarters and offices, and a list of present and former employees. In July 2011, LinkedIn launched a new feature allowing companies to include an "Apply with LinkedIn" button on job listing pages.[135] The new plugin allowed potential employees to apply for positions using their LinkedIn profiles as resumes.[135]

LinkedIn can help small businesses connect with customers.[136] In the site's parlance, two users have a "first-degree connection" when one accepts an invitation from another.[134] People connected to each of them are "second-degree connections" and persons connected to the second-degree connections are "third-degree connections."[134] This forms a user's internal LinkedIn network, making the user's profile more likely to appear in searches.

LinkedIn's Profinder is a marketplace where freelancers can (for a monthly subscription fee) bid for project proposals submitted by individuals and small businesses.[137] In 2017, it had around 60,000 freelancers in more than 140 service areas, such as headshot photography, bookkeeping or tax filing.[137]

The premise for connecting with someone has shifted significantly in recent years. Prior to the 2017 new interface being launched, LinkedIn encouraged connections between people who'd already worked together, studied together, done business together or the like. Since 2017 that step has been removed from the connection request process - and users are allowed to connect with up to 30,000 people. This change means LinkedIn is a more proactive networking site, be that for job applicants trying to secure a career move or for salespeople wanting to generate new client leads.[119]

Top Companies

[edit]LinkedIn Top Companies is a series of lists published by LinkedIn, identifying companies in the United States, Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, France, Germany, India, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Spain and the United Kingdom that are attracting the most intense interest from job candidates. The 2019 lists identified Google's parent company, Alphabet, as the most sought-after U.S. company, with Facebook ranked second and Amazon ranked third.[138] The lists are based on more than one billion actions by LinkedIn members worldwide. The Top Companies lists were started in 2016 and are published annually. The 2021 top list identified Amazon as the top company with Alphabet ranked second and JPMorgan & Chase Co. ranked third.[139]

Top Voices and other rankings

[edit]Since 2015 LinkedIn has published annual rankings of Top Voices on the platform, recognizing "members that generated the most engagement and interaction with their posts."[140] The 2020 lists[141] included 14 industry categories, ranging from data science to sports, as well as 14 country lists, extending from Australia to Italy.

LinkedIn also publishes data-driven annual rankings of the Top Startups in more than a dozen countries, based on "employment growth, job interest from potential candidates, engagement, and attraction of top talent."[142][143]

Advertising and for-pay research

[edit]In 2008 LinkedIn launched LinkedIn DirectAds as a form of sponsored advertising.[144] In October 2008, LinkedIn revealed plans to open its social network of 30 million professionals globally as a potential sample for business-to-business research. It is testing a potential social network revenue model – research that to some appears more promising than advertising.[145] On July 23, 2013, LinkedIn announced their Sponsored Updates ad service. Individuals and companies can now pay a fee to have LinkedIn sponsor their content and spread it to their user base. This is a common way for social media sites such as LinkedIn to generate revenue.[146]

LinkedIn launched its carousel ads feature in 2018, making it the newest addition to the platform’s advertising options. With carousel ads, businesses can showcase their products or services through a series of swipeable cards, each with its unique image, headline, and description. They can be used for a variety of marketing objectives, such as promoting a new product launch, driving website traffic, generating leads, or building brand awareness.

Business Manager

[edit]LinkedIn today[when?] announced the creation of Business Manager. The new Business Manager is a centralized platform designed to make it easier for large companies and agencies to manage people, ad accounts and business pages.[147]

Publishing platform

[edit]In 2015, LinkedIn added an analytics tool to its publishing platform. The tool allows authors to better track traffic that their posts receive. In relation to this functionality LinkedIn has gained more users over the years in the interest of clear monitoring of user's posts through post-performance analytics[148]

Future plans

[edit]Economic graph

[edit]Inspired by Facebook's "social graph", LinkedIn CEO Jeff Weiner set a goal in 2012 to create an "economic graph" within a decade.[149] The goal was to create a comprehensive digital map of the world economy and the connections within it.[150] The economic graph was to be built on the company's current platform with data nodes including companies, jobs, skills, volunteer opportunities, educational institutions, and content.[151][152] They have been hoping to include all the job listings in the world, all the skills required to get those jobs, all the professionals who could fill them, and all the companies (nonprofit and for-profit) at which they work. The ultimate goal is to make the world economy and job market more efficient through increased transparency.[149] In June 2014, the company announced its "Galene" search architecture to give users access to the economic graph's data with more thorough filtering of data, via user searches like "Engineers with Hadoop experience in Brazil."[153][154]

LinkedIn has used economic graph data to research several topics on the job market, including popular destination cities of recent college graduates,[155] areas with high concentrations of technology skills,[156] and common career transitions.[157] LinkedIn provided the City of New York with data from economic graph showing "in-demand" tech skills for the city's "Tech Talent Pipeline" project.[158]

Role in networking

[edit]LinkedIn has been described by online trade publication TechRepublic as having "become the de facto tool for professional networking".[159] LinkedIn has also been praised for its usefulness in fostering business relationships.[160] "LinkedIn is, far and away, the most advantageous social networking tool available to job seekers and business professionals today," according to Forbes.[161] LinkedIn has inspired the creation of specialised professional networking opportunities, such as co-founder Eddie Lou's Chicago startup, Shiftgig (released in 2012 as a platform for hourly workers).[162]

Criticism and controversies

[edit]Controversial design choices

[edit]Endorsement feature

[edit]The feature that allows LinkedIn members to "endorse" each other's skills and experience has been criticized as meaningless, since the endorsements are not necessarily accurate or given by people who have familiarity with the member's skills.[163] In October 2016, LinkedIn acknowledged that it "really does matter who endorsed you" and began highlighting endorsements from "coworkers and other mutual connections" to address the criticism.[164]

Use of e-mail accounts of members for spam sending

[edit]LinkedIn sends "invite emails" to Outlook contacts from its members' email accounts, without obtaining their consent. The "invitations" give the impression that the e-mail holder themself has sent the invitation. If there is no response, the answer will be repeated several times ("You have not yet answered XY's invitation.") LinkedIn was sued in the United States on charges of hijacking e-mail accounts and spamming. The company argued with the right to freedom of expression. In addition, the users concerned would be supported in building a network.[165][166][167]

The sign-up process includes users entering their email password (there is an opt-out feature). LinkedIn will then offer to send out contact invitations to all members in that address book or that the user has had email conversations with. When the member's email address book is opened, it is opened with all email addresses selected, and the member is advised invitations will be sent to "selected" email addresses, or to all. LinkedIn was sued for sending out another two follow-up invitations to each contact from members to link to friends who had ignored the initial, authorized invitation.

In November 2014 LinkedIn lost a motion to dismiss the lawsuit, in a ruling that the invitations were advertisements not broadly protected by free speech rights that would otherwise permit use of people's names and images without authorization.[168][169][170] The lawsuit was eventually settled in 2015 in favor of LinkedIn members.[82]

Moving emails to LinkedIn servers

[edit]At the end of 2013 it was announced that the LinkedIn app intercepted users' emails and quietly moved them to LinkedIn servers for full access.[171] LinkedIn used man-in-the-middle attacks.[172]

Security incidents

[edit]2012 hack

[edit]In June 2012 cryptographic hashes of approximately 6.4 million LinkedIn user passwords were stolen by Yevgeniy Nikulin and other hackers who then published the stolen hashes online.[173] This action is known as the 2012 LinkedIn hack. In response to the incident, LinkedIn asked its users to change their passwords. Security experts criticized LinkedIn for not salting their password file and for using a single iteration of SHA-1.[174] On May 31, 2013, LinkedIn added two-factor authentication, an important security enhancement for preventing hackers from gaining access to accounts.[175] In May 2016, 117 million LinkedIn usernames and passwords were offered for sale online for the equivalent of $2,200.[176] These account details are believed to be sourced from the original 2012 LinkedIn hack, in which the number of user IDs stolen had been underestimated. To handle the large volume of emails sent to its users every day with notifications for messages, profile views, important happenings in their network, and other things, LinkedIn uses the Momentum email platform from Message Systems.[177]

Potential 2018 breach, or extended impacts from earlier incidents

[edit]In July 2018 Credit Wise reported "dark web" email and password exposures from LinkedIn. Shortly thereafter, users began receiving extortion emails, using that information as "evidence" that users' contacts had been hacked, and threatening to expose pornographic videos featuring the users. LinkedIn asserts that this is related to the 2012 breach; however, there is no evidence that this is the case.[178]

2021 breaches

[edit]A breach disclosed in April 2021 affected 500 million users.[179][180] A breach disclosed in June 2021 was thought to have affected 92% of users, exposing contact information, employment information. LinkedIn asserted that the data was aggregated via web scraping from LinkedIn as well as several other sites, and noted that "only information that people listed publicly in their profiles" was included. [181][182]

Malicious behavior on LinkedIn

[edit]Phishing

[edit]In what is known as Operation Socialist, documents released by Edward Snowden in the 2013 global surveillance disclosures revealed that British Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) (an intelligence and security organisation) infiltrated the Belgian telecommunications network Belgacom by luring employees to a false LinkedIn page.[183]

In 2014 Dell SecureWorks Counter Threat Unit (CTU) discovered that Threat Group-2889, an Iran-based group, created 25 fake LinkedIn accounts. The accounts were either fully developed personas or supporting personas. They use spearphishing and malicious websites against their victims.[184]Template:Third-party inline

According to reporting by Le Figaro, France's General Directorate for Internal Security and Directorate-General for External Security believe that Chinese spies have used LinkedIn to target thousands of business and government officials as potential sources of information.[185]

In 2017 Germany's Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution (BfV) published information alleging that Chinese intelligence services had created fake social media profiles on sites such as LinkedIn, using them to gather information on German politicians and government officials.[186][187]

In 2022, the company ranked first in a list of brands most likely to be imitated in phishing attempts.[188]

False and misleading information

[edit]LinkedIn has come under scrutiny for its handling of misinformation and disinformation.[189] The platform has struggled to deal with fake profiles and falsehoods about COVID-19 and the 2020 US presidential election.[190][191][192]

Policies

[edit]Privacy policy

[edit]The German Stiftung Warentest has criticized that the balance of rights between users and LinkedIn is disproportionate, restricting users' rights excessively while granting the company far-reaching rights.[193] It has also been claimed that LinkedIn does not respond to consumer protection center requests.[194]

Research on labor market effects

[edit]In 2010, Social Science Computer Review published research by economists Ralf Caers and Vanessa Castelyns who sent an online questionnaire to 398 and 353 LinkedIn and Facebook users respectively in Belgium and found that both sites had become tools for recruiting job applicants for professional occupations as well as additional information about applicants, and that it was being used by recruiters to decide which applicants would receive interviews.[195] In May 2017, Research Policy published an analysis of PhD holders use of LinkedIn and found that PhD holders who move into industry were more likely to have LinkedIn accounts and to have larger networks of LinkedIn connections, were more likely to use LinkedIn if they had co-authors abroad, and to have wider networks if they moved abroad after obtaining their PhD.[196]

Also in 2017, sociologist Ofer Sharone conducted interviews with unemployed workers to research the effects of LinkedIn and Facebook as labor market intermediaries and found that social networking services (SNS) have had a filtration effect that has little to do with evaluations of merit, and that the SNS filtration effect has exerted new pressures on workers to manage their careers to conform to the logic of the SNS filtration effect.[197] In October 2018, Foster School of Business professors Melissa Rhee, Elina Hwang, and Yong Tan performed an empirical analysis of whether the common professional networking tactic by job seekers of creating LinkedIn connections with professionals who work at a target company or in a target field is actually instrumental in obtaining referrals and found instead that job seekers were less likely to be referred by employees who were employed by the target company or in the target field due to job similarity and self-protection from competition. Rhee, Hwang, and Tan further found that referring employees in higher hierarchical positions than the job candidates were more likely to provide referrals and that gender homophily did not reduce the competition self-protection effect.[198]

In July 2019, sociologists Steve McDonald, Amanda K. Damarin, Jenelle Lawhorne, and Annika Wilcox performed qualitative interviews with 61 human resources recruiters in two metropolitan areas in the Southern United States and found that recruiters filling low- and general-skilled positions typically posted advertisements on online job boards while recruiters filling high-skilled or supervisor positions targeted passive candidates on LinkedIn (i.e. employed workers not actively seeking work but possibly willing to change positions), and concluded that this is resulting in a bifurcated winner-takes-all job market with recruiters focusing their efforts on poaching already employed high-skilled workers while active job seekers are relegated to hyper-competitive online job boards.[199] In December 2001, the ACM SIGGROUP Bulletin published a study on the use of mobile phones by blue-collar workers that noted that research about tools for blue-collar workers to find work in the digital age was strangely absent and expressed concern that the absence of such research could lead to technology design choices that would concentrate greater power in the hands of managers rather than workers.[200][201]

In a September 2019, working paper, economists Laurel Wheeler, Robert Garlick, and RTI International scholars Eric Johnson, Patrick Shaw, and Marissa Gargano ran a randomized evaluation of training job seekers in South Africa to use LinkedIn as part of job readiness programs. The evaluation found that the training increased the job seekers employment by approximately 10 percent by reducing information frictions between job seekers and prospective employers, that the training had this effect for approximately 12 months, and that while the training may also have facilitated referrals, it did not reduce job search costs and the jobs for the treatment and control groups in the evaluation had equal probabilities of retention, promotion, and obtaining a permanent contract.[202] In 2020, Applied Economics published research by economists Steffen Brenner, Sezen Aksin Sivrikaya, and Joachim Schwalbach using LinkedIn demonstrating that high status individuals self-select into professional networking services rather than workers unsatisfied with their career status adversely selecting into the services to receive networking benefits.[203]

International restrictions

[edit]In 2009, Syrian users reported that LinkedIn server stopped accepting connections originating from IP addresses assigned to Syria. The company's customer support stated that services provided by them are subject to US export and re-export control laws and regulations and "As such, and as a matter of corporate policy, we do not allow member accounts or access to our site from Cuba, Iran, North Korea, Sudan, or Syria."[204]

In February 2011 it was reported that LinkedIn was being blocked in China after calls for a "Jasmine Revolution". It was speculated to have been blocked because it is an easy way for dissidents to access Twitter, which had been blocked previously.[205] After a day of being blocked, LinkedIn access was restored in China.[206]

In February 2014, LinkedIn launched its Simplified Chinese language version named "领英" (pinyin: Lǐngyīng; lit. 'leading elite'), officially extending their service in China.[207][208] LinkedIn CEO Jeff Weiner acknowledged in a blog post that they would have to censor some of the content that users post on its website in order to comply with Chinese rules, but he also said the benefits of providing its online service to people in China outweighed those concerns.[207][209] Since Autumn 2017 job postings from western countries for China aren't possible anymore.[210]

In 2016, a Moscow court ruled that LinkedIn must be blocked in Russia for violating a data retention law which requires the user data of Russian citizens to be stored on servers within the country. The relevant law had been in force there since 2014.[211][212] This ban was upheld on November 10, 2016, and all Russian ISPs began blocking LinkedIn thereafter. LinkedIn's mobile app was also banned from Google Play Store and iOS App Store in Russia in January 2017.[213][214] In July 2021 it was also blocked in Kazakhstan.[215]

In October 2021 after reports of several academicians and reporters who received notifications regarding their profiles will be blocked in China, Microsoft confirmed that LinkedIn will be shutting down in China and replaced with InJobs, a China exclusive app, citing difficulties in operating environments and increasing compliance requirements.[216] In May 2023, LinkedIn announced that it would be phasing out the app by 9 August 2023.[217]

Open source contributions

[edit]Since 2010 LinkedIn has contributed multiple internal technologies, tools, and software products to the open source domain.[218] Notable among these projects is Apache Kafka, which was built and open sourced at LinkedIn in 2011.[219] The team behind the creation of Kafka formed a LinkedIn spin-out company in 2014 named Confluent,[220] which went public with an IPO in 2021.[221] A list of LinkedIn's active open source projects can be found on their engineering website.[222]

Research using data from the platform

[edit]Massive amounts of data from LinkedIn allow scientists and machine learning researchers to extract insights and build product features.[223] For example, this data can help to shape patterns of deception in resumes. Findings suggested that people commonly lie about their hobbies rather than their work experience on online resumes.[224]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Microsoft Corporation Form 10-K". U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. July 28, 2022. p. 95.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "About". LinkedIn Corporation. 2015. Archived from the original on December 1, 2014. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- ^ "Microsoft buys LinkedIn". Stories. Retrieved May 25, 2023.

- ^ Lemann, Nicholas (October 12, 2015). "Reid Hoffman's Big Dreams for LinkedIn". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on May 1, 2021. Retrieved October 10, 2015.

- ^ "Account Restricted". LinkedIn Help Center. December 20, 2013. Archived from the original on August 19, 2020. Retrieved October 6, 2015.

- ^ "Locations - LinkedIn Careers". LinkedIn. Archived from the original on November 9, 2021. Retrieved November 10, 2021.

- ^ "LinkedIn Company Page". LinkedIn. Retrieved May 3, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Hempel, Jessi (July 1, 2013). "LinkedIn: How It's Changing Business". Fortune. pp. 69–74.

- ^ "LinkedIn – Management". LinkedIn Corporation. Archived from the original on February 20, 2009. Retrieved December 7, 2009.

- ^ "LinkedIn Secures $53M of Funding Led by Bain Capital Ventures" (Press release). LinkedIn. June 18, 2008. Archived from the original on August 2, 2013. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ^ "LinkedIn Raises $12.8 Million from Bessemer Venture Partners and European Founders Fund to Accelerate Global Growth" (Press release). LinkedIn. January 29, 2007. Archived from the original on November 1, 2013. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ^ "LinkedIn Premium Services Finding Rapid Adoption" (Press release). LinkedIn. March 7, 2006. Archived from the original on November 1, 2013. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ^ Swisher, Kara (January 27, 2011). "Here Comes Another Web IPO: LinkedIn S-1 Filing Imminent". All Things Digital. Archived from the original on May 26, 2011. Retrieved January 27, 2011.

- ^ "New Item on the College Admission Checklist: LinkedIn Profile". The New York Times. November 5, 2016. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved February 15, 2017.

- ^ Burns, John (July 14, 2015). "University Student's Guide to Creating a LinkedIn Profile". Wize. Archived from the original on February 26, 2021. Retrieved March 28, 2017.

- ^ Posner, Nico (June 21, 2011). "Look who's talking Russian, Romanian and Turkish now!". LinkedIn Blog. LinkedIn. Archived from the original on June 25, 2011. Retrieved June 21, 2011.

- ^ "LinkedIn launches in Japan". TranslateMedia. October 20, 2011. Archived from the original on October 26, 2011. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ^ Pepitone, Julianne (January 27, 2011). "LinkedIn files for IPO, reveals sales of $161 million". CNN. Archived from the original on January 29, 2011. Retrieved January 28, 2011.

- ^ "Founders". LinkedIn. Archived from the original on February 14, 2015. Retrieved July 15, 2016.

- ^ "Sequoia Capital "Links In" with $4.7 Million Investment". press.linkedin.com. Retrieved December 11, 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Byers, Ann (July 15, 2013). Reid Hoffman and Linkedin. The Rosen Publishing Group. pp. 2003–. ISBN 978-1-4488-9537-3. Archived from the original on July 6, 2018. Retrieved December 1, 2016.

- ^ "Announcing LinkedIn Mobile (includes an iPhone version)". Archived from the original on September 20, 2016. Retrieved September 11, 2016.

- ^ Guynn, Jessica (June 18, 2008). "Professional networking site LinkedIn valued at $1 billion". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 22, 2008. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ^ Shinde, Shivani (December 17, 2009). "LinkedIn's first Asia-Pac office in India". Business Standard India. Archived from the original on January 5, 2018. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- ^ "LinkedIn establishment of International Headquarters in Dublin welcomed by IDA Ireland" (Press release). IDA Ireland. March 23, 2010. Archived from the original on October 25, 2012. Retrieved August 2, 2013.

- ^ Levy, Ari (July 28, 2010). "Tiger Global Said to Invest in LinkedIn at $2 billion Valuation". Bloomberg. Bloomberg L.P. Archived from the original on December 29, 2011. Retrieved May 16, 2013.

- ^ Hardy, Quentin (August 4, 2010). "LinkedIn Hooks Up". Forbes. Archived from the original on August 5, 2010. Retrieved August 5, 2010.

- ^ "Does local beat global in the professional-networking business?". The Economist. November 19, 2009. Archived from the original on November 28, 2009. Retrieved August 5, 2010.

- ^ Fusfeld, Adam (September 23, 2010). "2010 Digital 100 Companies 1–100". Business Insider. Archived from the original on December 13, 2010. Retrieved December 17, 2010.

- ^ Demos, Telis; Menn, Joseph (January 27, 2011). "LinkedIn looks for boost with IPO". Financial Times. Archived from the original on June 3, 2020. Retrieved June 4, 2020.Template:Registration required

- ^ "Social Network Ads: LinkedIn Falls Behind Twitter; Facebook Biggest of All" Archived February 3, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Lunden, Ingrid January 31, 2012.

- ^ "Stocks to Watch: Nuance Communications, LinkedIn, Merck and More" Archived October 18, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. Thomson Maya and Pope-Chappell Maya February 13, 2012.

- ^ "About Us – LinkedIn". LinkedIn. Archived from the original on February 4, 2015. Retrieved June 13, 2016.

- ^ "LinkedIn leases 26-story S.F. skyscraper". SFGate. April 23, 2014. Archived from the original on October 20, 2014. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "LinkedIn connects all its S.F. employees under one roof at Tishman Speyer's tower at 222 Second St". San Francisco Business Times. March 25, 2016. Archived from the original on February 27, 2017. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- ^ Cohen, Luc (February 8, 2016). "CEOs, venture backers lose big as LinkedIn, Tableau shares tumble". Reuters. Archived from the original on June 20, 2017. Retrieved July 1, 2017.

- ^ Rosenfeld, Everett (February 5, 2016). "LinkedIn skids 40%, erases $10B in market cap". Cnbc.com. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved June 10, 2016.

- ^ Maida, Adam (June 18, 2020). "Online and On All Fronts: Russia's Assault on Freedom of Expression". Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on August 10, 2020. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- ^ Greene, Jay; Steele, Anne (June 13, 2016). "Microsoft to Acquire LinkedIn for $26.2 Billion". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on January 24, 2021. Retrieved June 13, 2016.

- ^ O'Brien, Ciara (November 29, 2016). "LinkedIn to add 200 jobs at its EMEA HQ in Dublin". Irish Times. Archived from the original on February 22, 2017. Retrieved February 15, 2017.

- ^ Rynne, Alexandra (February 1, 2017). "10 Surprising Stats You Didn't Know about Marketing on LinkedIn". LinkedIn Marketing Solutions Blog. Archived from the original on October 11, 2018. Retrieved October 15, 2018.

- ^ LinkedIn Corporate Communications Team for LinkedIn Newsroom. January 19, 2017 Introducing the New LinkedIn Desktop Archived January 27, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Filtering and Tagging Connections Feature – No Longer Available". LinkedIn Help Pages. February 2, 2017.

- ^ "LinkedIn Brings Its 'Open for Business' Feature to India". NDTV Gadgets 360. Archived from the original on January 13, 2021. Retrieved January 13, 2021.

- ^ "Open for Business: LinkedIn launches 'Open for Business' feature globally for SMEs". The Economic Times. Archived from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved January 13, 2021.

- ^ "LinkedIn Launches Events to Facilitate Professional Meet-Ups". Social Media Today. October 17, 2019. Archived from the original on February 10, 2021. Retrieved January 13, 2021.

- ^ "LinkedIn Launches Its Own Events Feature". WeRSM - We are Social Media. October 17, 2019. Archived from the original on December 6, 2020. Retrieved January 13, 2021.

- ^ Arbel, Tali (February 5, 2020). "LinkedIn CEO steps aside after 11 years, says time is right". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on February 6, 2020. Retrieved February 6, 2020.

- ^ Holt, Kris (July 21, 2020). "LinkedIn will cut nearly 1,000 jobs as pandemic slows global hiring". Engadget. Archived from the original on July 21, 2020. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- ^ "LinkedIn Leak - 500M Records Leaked and Being Sold". CyberNews. April 6, 2021. Archived from the original on April 12, 2021. Retrieved April 12, 2021.

- ^ "An update on report of scraped data". news.linkedin.com. Archived from the original on April 12, 2021. Retrieved April 12, 2021.

- ^ Peters, Jay (April 8, 2021). "Another 500 million accounts have leaked online, and LinkedIn's in the hot seat". The Verge. Archived from the original on April 12, 2021. Retrieved April 12, 2021.

- ^ Paul Wagenseil (June 29, 2021). "700 million exposed in LinkedIn data scrape — what to do now". Tom's Guide. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 6, 2021.

- ^ Lovejoy, Ben (June 29, 2021). "LinkedIn breach reportedly exposes data of 92% of users". 9to5Mac. Archived from the original on July 6, 2021. Retrieved July 6, 2021.

- ^ "Exclusive: 700 Million LinkedIn Records Leaked June 2021 | Safety First". PrivacySharks. June 27, 2021. Archived from the original on July 6, 2021. Retrieved July 6, 2021.

- ^ Woo, Liza Lin and Stu (October 14, 2021). "Microsoft Folds LinkedIn Social-Media Service in China". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on October 14, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ^ "Tech layoffs: LinkedIn cuts 700 jobs and closes China app". BBC.

- ^ Digg Sold To LinkedIn AND The Washington Post And Betaworks Archived December 16, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, TechCrunch.com, July 2012

- ^ Jump up to: a b "SEC S/1 Filing". SEC. November 3, 2011. Archived from the original on November 1, 2013. Retrieved November 3, 2011.

- ^ Schwartzel, Erich (August 4, 2010). "CMU startup mSpoke acquired by LinkedIn". post-gazette. Archived from the original on September 9, 2013. Retrieved August 4, 2010.

- ^ "List of Notable Businesses Acquired by LinkedIn". Kennected. March 19, 2020. Archived from the original on March 27, 2020. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

- ^ "LinkedIn acquires ChoiceVendor". BusinessWire. September 23, 2010. Archived from the original on November 23, 2016. Retrieved November 23, 2016 – via businesswire.com.

- ^ "LinkedIn S1 Filing". SEC. January 26, 2011. Archived from the original on December 20, 2018. Retrieved February 24, 2012.

- ^ "LinkedIn Acquires Social CRM Company Connected". Forbes. October 5, 2011. Archived from the original on March 6, 2022. Retrieved September 22, 2021.

- ^ "LinkedIn Buys Real-Time, Hosted Search Startup IndexTank". TechCrunch. October 11, 2011. Archived from the original on August 15, 2018. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ "Rapportive Announces Acquisition By LinkedIn". TechCrunch. February 12, 2012. Archived from the original on August 15, 2018. Retrieved February 12, 2012.

- ^ "LinkedIn acquires Rapportive Gmail Contact plugin". eweek. February 24, 2012. Archived from the original on October 18, 2017. Retrieved February 24, 2012.

- ^ "LinkedIn Is Buying SlideShare for $119 Million". Business Insider. May 3, 2012. Archived from the original on February 11, 2013. Retrieved February 18, 2013.

- ^ "LinkedIn Acquires Pulse For $90M In Stock And Cash". TechCrunch. April 11, 2013. Archived from the original on January 15, 2019. Retrieved April 11, 2013.

- ^ "LinkedIn makes its biggest acquisition by paying $120m for job matching service Bright". TNW. February 6, 2014. Archived from the original on April 21, 2014. Retrieved April 20, 2014.

- ^ "LinkedIn Acquires Start-Up Newsle". July 14, 2014. Archived from the original on July 19, 2014. Retrieved July 23, 2014.

- ^ Gelles, David (July 22, 2014). "LinkedIn Makes Another Deal, Buying Bizo". DealBook. New York Times. Archived from the original on July 9, 2017. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ^ Lunden, Ingrid (March 16, 2016). "LinkedIn Buys Careerify to Build out its Recruitment Business". Tech Crunch. Tech Crunch. Archived from the original on March 17, 2015. Retrieved March 16, 2015.

- ^ Ingrid, Lunden (April 2, 2015). "LinkedIn Buys Refresh.io To Add Predictive Insights To Its Products". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on April 4, 2015. Retrieved April 6, 2015.

- ^ KOSOFF, MAYA (April 9, 2015). "LinkedIn just bought online learning company Lynda for $1.5 billion". BusinessInsider. Archived from the original on June 4, 2020. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ^ "LinkedIn acquires predictive marketing firm Fliptop to boost its Sales Solutions offering". VentureBeat. August 29, 2015. Archived from the original on October 10, 2017. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ "LinkedIn acquires recruiting startup Connectifier". VentureBeat. February 5, 2016. Archived from the original on July 27, 2017. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ "LinkedIn buys PointDrive to boost its social sales platform with sharing". TechCrunch. July 26, 2016. Archived from the original on July 27, 2016. Retrieved July 26, 2016.

- ^ "LinkedIn acquires employee engagement platform Glint". TechCrunch. October 8, 2018. Archived from the original on January 15, 2019. Retrieved January 8, 2019.

- ^ "Helping Businesses Succeed with LinkedIn". business.linkedin.com. Archived from the original on March 7, 2020. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- ^ "PacerMonitor Document View – 5:13-cv-04303 – Perkins et al v. LinkedIn Corporation, Docket Item 1" (PDF). Pacermonitor.com. September 17, 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 7, 2015. Retrieved October 6, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "LinkedIn settles class-action lawsuit – Business Insider". Business Insider. October 2, 2015. Archived from the original on October 4, 2015. Retrieved October 3, 2015.

- ^ UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT, NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA SAN JOSE DIVISION (September 17, 2013). "Preliminary Approval Order" (PDF). addconnectionssettlement.com. GILARDI & CO LLC. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 18, 2017. Retrieved October 26, 2016.

- ^ "400 Million Members!". LinkedIn Blog. LinkedIn. October 29, 2015. Archived from the original on October 30, 2015. Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- ^ "Now at 50 m users, LinkedIn rival Viadeo acquires French startup Pealk and announces US innovation lab". January 14, 2013. Archived from the original on August 15, 2018. Retrieved June 18, 2018.

- ^ "XING AG". corporate.xing.com. Archived from the original on August 3, 2016. Retrieved September 10, 2016.

- ^ "LinkedIn now adding two members every second". TechCrunch.com. August 4, 2011. Archived from the original on November 3, 2011. Retrieved October 31, 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "About LinkedIn". about.linkedin.com. Archived from the original on May 28, 2021. Retrieved December 16, 2019.

- ^ Spiegel, Linda (June 1, 2016). "How Job Hunters Should Use LinkedIn Second-Degree Connections". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on June 26, 2016. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- ^ "EU Data Transfers | LinkedIn Help". www.linkedin.com. Archived from the original on April 10, 2019. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- ^ "Introducing LinkedIn Video: Show Your Experience and Perspective". blog.linkedin.com. Archived from the original on May 20, 2018. Retrieved December 1, 2017.

- ^ "LinkedIn Just Launched Some Snapchat-Like Features for Video Creators". Archived from the original on March 21, 2018. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ "Linkedin Publishing". www.linkedin.com. Archived from the original on January 13, 2018. Retrieved December 1, 2017.

- ^ "How to endorse someone on LinkedIn, or accept a LinkedIn endorsement for your profile". BusinessInsider. Archived from the original on December 28, 2021. Retrieved December 28, 2021.

- ^ Taub, Eric A. (December 4, 2013). "The Path to Happy Employment, Contact by Contact on LinkedIn". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 22, 2017. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ^ Terms of Use Archived December 20, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, LinkedIn, February 12, 2015

- ^ "Developers | Linkedin". Archived from the original on December 13, 2016. Retrieved December 4, 2016.

- ^ Facebook in a Suit: LinkedIn Launches Applications Platform Archived January 23, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Business Week, October 28, 2008

- ^ "LinkedIn Adopts 'Recommend' Over 'Like'" Archived November 5, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, Clickz.com, November 2, 2010

- ^ "Social-networking site LinkedIN introduces mobile version". tweakers.net. Archived from the original on February 26, 2008. Retrieved February 25, 2008.

- ^ CardMunch acquired by LinkedIn Archived March 13, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, shoutEx.com Feb 2011

- ^ "Announcement". Engineering.linkedin.com. October 23, 2013. Archived from the original on December 4, 2013. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ Fox, Bishop (October 23, 2013). "LinkedIn 'Intro'duces Insecurity". Bishop Fox. Archived from the original on October 7, 2015. Retrieved October 6, 2015.

- ^ Fox, Bishop (November 1, 2013). "An Introspection On Intro Security". Bishop Fox. Archived from the original on October 6, 2015. Retrieved October 6, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Groups Directory". LinkedIn. Retrieved December 8, 2011.

- ^ "World's Largest LinkedIn Group Breaks The 700,000 Member mark". i-newswire.com. Archived from the original on April 17, 2012. Retrieved February 28, 2012.

- ^ "How to Avoid LinkedIn's Site Wide Automatic Moderation (SWAM)". Socialmediatoday.com. Archived from the original on June 27, 2014. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- ^ Lerner, Mark. "How To Avoid LinkedIn's Site Wide Automatic Moderation". Oktopost. Archived from the original on March 24, 2014. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ^ "Groups". LinkedIn Corporation. Archived from the original on March 10, 2012. Retrieved March 26, 2012.

- ^ Wasserman, Todd (December 14, 2011). "LinkedIn polling". Mashable. Archived from the original on December 15, 2011. Retrieved December 15, 2011.

- ^ Pinkovezky, Aviad (November 19, 2013). "Announcing LinkedIn Showcase Pages". Archived from the original on October 11, 2014. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

- ^ Everett, Paul (August 6, 2014). "LinkedIn Company Product & Services pages being discontinued". Archived from the original on March 6, 2022. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

- ^ Levin, Valerie (June 29, 2014). "Crash Course: LinkedIn Showcase Pages 101". Archived from the original on October 16, 2014. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

- ^ "Building The LinkedIn Knowledge Graph". engineering.linkedin.com. Archived from the original on September 22, 2020. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "Machine Learning in LinkedIn Knowledge Graph". www.linkedin.com. Archived from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "LinkedIn Is Quietly Retiring Network Visualization Tool InMaps". September 2, 2014. Archived from the original on November 1, 2017. Retrieved November 27, 2017.

- ^ Joel, CHEESMAN (May 1, 2018). "LinkedIn Referrals Set to Close Down Later This Month". ERE. Archived from the original on August 2, 2019. Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- ^ "Update about Marketing with LinkedIn Stories, and What's Next". www.linkedin.com. Archived from the original on December 7, 2021. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Long, Sandra (2016). LinkedIn for Personal Branding: The Ultimate Guide. New York City: HGP Publishing. p. 3,6,18,23,25,73,74,133. ISBN 9781938015434.

- ^ Soule, Alexander (February 28, 2016). "Indeed adding to job-searching workforce in Stamford". Stamford Advocate. Archived from the original on August 18, 2019. Retrieved August 19, 2019.

... LinkedIn is a social network," said Sandra Long, who provides LinkedIn training through her Post Road Consulting, which has offices in Westport and Stamford "... LinkedIn has also evolved into a platform for sales and other business professionals to manage a personal 'brand' ... you can identify the exact people you know that are connected to that opportunity."...

- ^ Shoop, Julie (August 12, 2019). "#ASAE19: STRENGTHEN YOUR PERSONAL BRAND". Associations Now. Archived from the original on August 18, 2019. Retrieved August 19, 2019.

...Green ... describes a personal brand as "the emotional experience you want people to have as a result of interacting with you."...

- ^ Samuel, Alexandra (August 11, 2019). "A Social-Media Guide for Introverts". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on August 19, 2019. Retrieved August 19, 2019.

... a "personal brand": a public-facing persona, exhibited on LinkedIn, Twitter and other networks, that showcases expertise and fosters new connections....

- ^ Jump up to: a b Meyer, Jack (July 14, 2019). "How to Use LinkedIn to Find a Job in 2019:LinkedIn connects over 600 million users between roughly 200 countries. With so many people using it, how can you stand out from the crowd to land that next job?". TheStreet.com. Archived from the original on August 3, 2019. Retrieved August 3, 2019.

...Linked ... grown into the premier digital platform ...

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bariso, Justin (August 1, 2019). "How to Use LinkedIn and LinkedIn Video to Expand Your Reach, Build Your Network, and Find the Right Customers for Your Business: LinkedIn has changed dramatically through the years. Here's a step-by-step guide for getting the most out of the platform". Inc. Archived from the original on August 3, 2019. Retrieved August 3, 2019.

... Advice from Kristin Sherry -- engage with commenters, give give give, ask for engagement, don't be a slave to numbers, experiment with LinkedIn video...

- ^ Collamer, Nancy (March 7, 2017). "7 LinkedIn Tips To Build Your Personal Brand". Forbes. Archived from the original on June 11, 2019. Retrieved August 19, 2019.

...Invest in getting a professional photo taken ... Long says: "If you can afford a professional photographer, it is usually the best investment you can make in your personal brand and self confidence."...

- ^ "5 tips to make LinkedIn work better". Enterprisers Project. January 4, 2019. Archived from the original on August 18, 2019. Retrieved August 19, 2019.

..Consider adding [...videos] to your profile, or uploading presentations to LinkedIn via SlideShare," says Sandra Long, author of "LinkedIn for Personal Branding: The Ultimate Guide...

- ^ Jump up to: a b Moran, Gwen (July 20, 2017). "Give your LinkedIn profile a complete makeover in under an hour: Need to spruce up your LinkedIn profile fast? Focus on these seven areas". Fast Company. Archived from the original on August 12, 2019. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

... a cottage industry has sprung up around helping people and companies craft the perfect profile of record ... Your headline is the 120-word line ... Be sure you're using that space wisely, says Sandra Long, LinkedIn consultant and author of LinkedIn for Personal Branding: The Ultimate Guide....

- ^ Reyes, Maridel (December 2, 2018). "How to make the perfect LinkedIn profile". New York Post. Archived from the original on August 12, 2019. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

... A comprehensive profile includes a headline with keywords; headshot photo; first-person summary and experiences; education; skills; geography; industry; contact information; volunteering; custom URL and accomplishments such as publications, organizations, awards, spoken languages and certifications, says Sandra Long, author of "LinkedIn for Personal Branding: The Ultimate Guide"...

- ^ Passy, Jacob (April 2, 2017). "This is the country (and profession) with the most photogenic LinkedIn profiles". MarketWatch. Archived from the original on August 12, 2019. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

...There's no hiding in the long grass on LinkedIn ... said Sandra Long, owner of Post Road Consulting, a company that provides LinkedIn training ...

- ^ "Will LinkedIn Address the Influencer Program's Gender Lopsidedness?" Archived March 6, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, LinkedIn Pulse, June 14, 2016. Retrieved on June 28, 2016.

- ^ Rao, Leena. "LinkedIn Allows You To Follow Key Influencers On The Network; Will Eventually Make Feature Universal" Archived July 5, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, TechCrunch, San Francisco, October 2, 2012. Retrieved on July 19, 2013.

- ^ Kaufman, Leslie. "LinkedIn Builds Its Publishing Presence" Archived July 1, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, New York, June 16, 2013. Retrieved on July 19, 2013.

- ^ Santoreneos, Anastasia (August 1, 2019). "How to use LinkedIn to guarantee you get your dream job". Yahoo! Finance. Archived from the original on August 3, 2019. Retrieved August 3, 2019.

...LinkedIn, the professional's Facebook ... there are around 12.5 million working professionals in Australia - which means your future employer is probably on the site...

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Kersten, Teresa (July 16, 2019). "How to Get Positive Responses to Cold Outreach Messages on LinkedIn". Yahoo! Finance. Archived from the original on August 3, 2019. Retrieved August 3, 2019.

.... People you've accepted invitations from (or those who've accepted them from you) are first-degree connections. People connected to them are second-degree, and those connected to second-degree connections are third-degree. ... ...

- ^ Jump up to: a b Colleen Taylor, GigaOm. "LinkedIn launches job application plugin Archived October 8, 2011, at the Wayback Machine." July 25, 2011. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- ^ Economy, Peter (July 23, 2019). "If You're Freelance or a Small-Business Owner, LinkedIn Just Revealed a New Feature That Changes Everything: LinkedIn counts at least 10 million small-business leaders who use the site's tools and services to reach out to clients". Inc. Archived from the original on March 6, 2022. Retrieved August 3, 2019.

... enable members who are freelancers and small business owners to show their individual availability,..

- ^ Jump up to: a b Petrow, Steven (May 10, 2017). "3 overlooked LinkedIn features to find a better paying job". USA Today. Archived from the original on March 18, 2020. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ^ Roth, Daniel (April 3, 2019). "LinkedIn Top Companies 2019: Where the U.S. wants to work now". LinkedIn.

- ^ "LinkedIn Unveils the 2021 U.S. Top Companies List". www.businesswire.com. April 28, 2021. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved September 23, 2021.

- ^ Hutchinson, Andrew (November 17, 2020). "LinkedIn shares listing of its most influential users in 2020". Social Media Today. Archived from the original on August 10, 2021. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ Roth, Daniel (November 17, 2020). "LinkedIn Top Voices: meet the professionals driving today's business conversations". Archived from the original on July 22, 2021. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ Kambhammettu, Akhil (September 29, 2020). "10 Companies That Are Thriving--and Hiring--Amid the Pandemic". Inc. Archived from the original on July 22, 2021. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ Hempel, Jessi (September 22, 2020). "LinkedIn Top Startups 2020: The 50 U.S. companies on the rise". Archived from the original on July 22, 2021. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ "LinkedIn Direct Ads vs Google Adwords". Shoutex.com. December 22, 2008. Archived from the original on October 8, 2015. Retrieved October 6, 2015.

- ^ LinkedIn's promising new revenue model: sending you surveys. By: Neff, Jack, Advertising Age, 00018899, October 27, 2008, Vol. 79, Issue 40. Database: Business Source Complete

- ^ "LinkedIn Expands Ad Program With Launch Of Sponsored Updates Program". Techcruch.com. July 23, 2013. Archived from the original on April 21, 2021. Retrieved October 6, 2015.

- ^ "Get started with LinkedIn Business Manager - 3 Advantages". Infin Digital. July 27, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ^ By Ingrid Lunden, TechCrunch. ""Who's Viewed Your Posts?" LinkedIn Adds Analytics To Its Publishing Platform Archived April 21, 2021, at the Wayback Machine." May 7, 2015. May 7, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Steve Kovach November 27, 2012 Jeff Weiner Just Revealed A Surprising Long-Term Vision For LinkedIn Archived March 6, 2022, at the Wayback Machine Business Insider

- ^ Rachel King September 9, 2013 LinkedIn's long-term plan? Build the 'world's first economic graph,' says CEO Archived June 19, 2014, at the Wayback Machine ZDNet's Between the Lines

- ^ Ingrid Lunden January 15, 2014 LinkedIn Expands Its Jobs Database With A New Volunteer Marketplace For Unpaid Non-Profit Work Archived July 9, 2017, at the Wayback Machine TechCrunch

- ^ Bill Chappell August 19, 2013 University Pages: LinkedIn Launches New College Profiles Archived April 24, 2015, at the Wayback Machine NPR's the two-way

- ^ Harrison Weber June 5, 2014 LinkedIn launches ‘Galene’ search architecture to build the first ‘economic graph’ Archived July 27, 2017, at the Wayback Machine VentureBeat

- ^ Rachel King June 5, 2014 LinkedIn plans to reinvent search in order to map its economic graph Archived July 4, 2014, at the Wayback Machine ZDNet's Between the Lines

- ^ "The most attractive cities worldwide for new graduates – Quartz". Quartz. June 4, 2014. Archived from the original on October 13, 2015. Retrieved October 6, 2015.

- ^ "Where Is the Top City to Spot Tech Talent?". Blogs.wsj.com. June 24, 2014. Archived from the original on October 6, 2015. Retrieved October 6, 2015.

- ^ "Oh, the Places You'll Go! (Or Not.)". Blogs.wsj.com. December 8, 2014. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved October 6, 2015.

- ^ "LinkedIn Economic Graph Research: Helping New Yorkers Connect With The Jobs Of Tomorrow [INFOGRAPHIC]". Blog.linkedin.com. Archived from the original on July 4, 2015. Retrieved July 3, 2015.

- ^ "Five Benefits of LinkedIn for Organizations (and IT Pros) | TechRepublic." Web. May 9, 2011.

- ^ "LinkedIn.com, a business-orientated networking site, can be an ideal way for professionals to present an online profile of themselves ... Unlike social networking sites, [with] LinkedIn you're outlining all your credentials; presenting the professional rather than the personal you. Considering the sheer vastness of the digital space, the potential for building up a solid base of contacts and fostering new business relationships is boundless." O'Sullivan, James (2011), "Make the most of the networking tools that are available", Evening Echo, May 9, 2011. Pg 32. Note that the Evening Echo is located close to the European headquarters of LinkedIn

- ^ Foss, Jenny (July 6, 2012). "Your LinkedIn Intervention: 5 Changes You Must Make". Forbes. Archived from the original on November 16, 2018. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ MacArthur, Kate. "Shiftgig hires LinkedIn vice president as new CEO". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on September 19, 2017. Retrieved September 20, 2017.

- ^ "All you need to know about endorsements". Forbes. Archived from the original on April 28, 2014. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- ^ "LinkedIn is making its endorsements feature a lot smarter to help people find jobs". Business Insider. Archived from the original on March 26, 2017. Retrieved March 26, 2017.

- ^ LinkedIn argues it has free speech right to email Archived January 4, 2018, at the Wayback Machine Mediapost.com on September 19, 2014.

- ^ LinkedIn 'Credit Reports' Give Job Seekers Trouble Courthouse News Service on October 13, 2014.

- ^ LinkedIn illegally sold your professional data lawsuit claims Archived March 6, 2022, at the Wayback Machine News Mic on October 13, 2014.

- ^ LinkedIn to face lawsuit for spamming users' email address books Archived March 6, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, BetaNews

- ^ LinkedIn is "breaking into" user emails, spamming contacts – lawsuit Archived June 17, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, Gigaom.com

- ^ "Judge Rejects LinkedIn's Free-Speech Argument In Battle Over Email Invitations". Mediapost.com. Archived from the original on July 4, 2015. Retrieved July 3, 2015.

- ^ LinkedIns new mobile app called a dream for attackers Archived January 4, 2018, at the Wayback Machine New York Times on October 24, 2013.

- ^ LinkedIn liest Ihre Mails mit Archived May 5, 2017, at the Wayback Machine PC-Welt on October 28, 2013.

- ^ "LinkedIn Confirms Account Passwords Hacked". PC World.com. June 6, 2012. Archived from the original on September 14, 2012. Retrieved June 6, 2012.