Israel

Etymology

[edit]Upon independence in 1948, the country formally adopted the name "State of Israel" (Medinat Yisrael) after other proposed historical and religious names including Eretz Israel ("the Land of Israel"), Zion, and Judea, were considered and rejected. In the early weeks of independence, the government chose the term "Israeli" to denote a citizen of Israel, with the formal announcement made by Minister of Foreign Affairs Moshe Sharett.

The names Land of Israel and Children of Israel have historically been used to refer to the biblical Kingdom of Israel and the entire Jewish nation respectively. The name "Israel" in these phrases refers to the patriarch Jacob (Standard , ; Septuagint Israēl; "struggle with God") who, according to the Hebrew Bible, was given the name after he successfully wrestled with the angel of the Lord. Jacob's twelve sons became the ancestors of the Israelites, also known as the Twelve Tribes of Israel or Children of Israel. Jacob and his sons had lived in Canaan but were forced by famine to go into Egypt for four generations until Moses, a great-great grandson of Jacob, led the Israelites back into Canaan during the "Exodus". The earliest known archaeological artifact to mention the word "Israel" is the Merneptah Stele of ancient Egypt (dated to the late 13th century BCE).

The area is also known as the Holy Land, being holy for all Abrahamic religions including Judaism, Christianity, Islam and the Bahá'í Faith. From 1920 the whole region was known as Palestine (under British Mandate) until the Israeli Declaration of Independence of 1948. Through the centuries, the territory was known by a variety of other names, including Judea, Samaria, Southern Syria, Syria Palaestina, Kingdom of Jerusalem, Iudaea Province, Coele-Syria, Retjenu, and Canaan.

History

[edit]Antiquity

[edit]

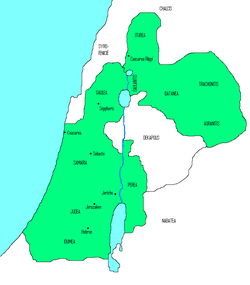

The notion of the "Land of Israel", known in Hebrew as Eretz Yisrael, has been important and sacred to the Jewish people since Biblical times. According to the Torah, God promised the land to the three Patriarchs of the Jewish people.[1][2] On the basis of scripture, the period of the three Patriarchs has been placed somewhere in the early 2nd millennium BCE,[3] and the first Kingdom of Israel was established around the 11th century BCE. Subsequent Israelite kingdoms and states ruled intermittently over the next four hundred years, and are known from various extra-biblical sources.[4][5][6][7]

The first record of the name Israel (as ysrỉꜣr) occurs in the Merneptah stele, erected for Egyptian Pharaoh Merneptah c. 1209 BCE, "Israel is laid waste and his seed is not."[8] This "Israel" was a cultural and probably political entity of the central highlands, well enough established to be perceived by the Egyptians as a possible challenge to their hegemony, but an ethnic group rather than an organised state;[9] Ancestors of the Israelites may have included Semites native to Canaan and the Sea Peoples.[10] McNutt says, "It is probably safe to assume that sometime during Iron Age a population began to identify itself as 'Israelite'", differentiating itself from the Canaanites through such markers as the prohibition of intermarriage, an emphasis on family history and genealogy, and religion.[11]

Villages had populations of up to 300 or 400,[12][13] which lived by farming and herding, and were largely self-sufficient;[14] economic interchange was prevalent.[15] Writing was known and available for recording, even in small sites.[16] The archaeological evidence indicates a society of village-like centres, but with more limited resources and a small population.[17] Modern scholars see Israel arising peacefully and internally from existing people in the highlands of Canaan.[18]

Around 930 BCE, the kingdom split into a southern Kingdom of Judah and a northern Kingdom of Israel. From the middle of the 8th century BCE Israel came into increasing conflict with the expanding neo-Assyrian empire. Under Tiglath-Pileser III it first split Israel's territory into several smaller units and then destroyed its capital, Samaria (722 BCE). An Israelite revolt (724–722 BCE) was crushed after the siege and capture of Samaria by the Assyrian king Sargon II. Sargon's son, Sennacherib, tried and failed to conquer Judah. Assyrian records say he leveled 46 walled cities and besieged Jerusalem, leaving after receiving extensive tribute.[19]

In 586 BCE King Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon conquered Judah. According to the Hebrew Bible, he destroyed Solomon's Temple and exiled the Jews to Babylon. The defeat was also recorded by the Babylonians[20][21] (see the Babylonian Chronicles).

In 538 BCE, Cyrus the Great of Persia conquered Babylon and took over its empire. Cyrus issued a proclamation granting subjugated nations (including the people of Judah) religious freedom (for the original text see the Cyrus Cylinder). According to the Hebrew Bible 50,000 Judeans, led by Zerubabel, returned to Judah and rebuilt the temple. A second group of 5,000, led by Ezra and Nehemiah, returned to Judah in 456 BCE although non-Jews wrote to Cyrus to try to prevent their return.

Classical period

[edit]

With successive Persian rule, the region, divided between Syria-Coele province and later the autonomous Yehud Medinata, was gradually developing back into urban society, largely dominated by Judeans. The Greek conquests largely skipped the region without any resistance or interest. Incorporated into Ptolemaic and finally Seleucid Empires, southern Levant was heavily hellenized, building the tensions between Judeans and Greeks. The conflict erupted in 167 BCE with the Maccabean Revolt, which succeeded in establishing an independent Hasmonean Kingdom in Judah, which later expanded over much of modern Israel, as the Seleucids gradually lost control in the region.

The Roman Empire invaded the region in 63 BCE, first taking control of Syria, and then intervening in the Hasmonean civil war. The struggle between pro-Roman and pro-Parthian factions in Judea eventually led to the installation of Herod the Great and consolidation of the Herodian Kingdom as a vassal Judean state of Rome.

With the decline of Herodians, Judea, transformed into a Roman province, became the site of a violent struggle of Jews against Greco-Romans, culminating in the Jewish-Roman Wars, ending in wide-scale destruction, expulsions, and genocide. Jewish presence in the region significantly dwindled after the failure of the Bar Kokhba revolt against the Roman Empire in 132 CE.[23] Nevertheless, there was a continuous small Jewish presence and Galilee became its religious center.[24][25] The Mishnah and part of the Talmud, central Jewish texts, were composed during the 2nd to 4th centuries CE in Tiberias and Jerusalem.[26] The region came to be populated predominantly by Greco-Romans on the coast and Samaritans in the hill-country. Christianity was gradually evolving over Roman paganism, when the area under Byzantine rule was transformed into Deocese of the East, as Palaestina Prima and Palaestina Secunda provinces. Through the 5th and 6th centuries, dramatic events of Samaritan Revolts reshaped the land, with massive destruction to Byzantine Christian and Samaritan societies and a resulting decrease of the population. After the Persian conquest and the installation of a short-lived Jewish Commonwealth in 614 CE, the Byzantine Empire reinstalled its rule in 625 CE, resulting in further decline and destruction.

Middle Ages and caliphates

[edit]

In 635 CE, the region, including Jerusalem, was conquered by Arabs. It remained under Muslim control and predominately Muslim occupancy for the next 1300 years under various caliphates.[28] Control of the region transferred between the Umayyads,[28] Abbasids,[28] and Crusaders throughout the next six centuries,[28] before the area was conquered in 1260 by the Mamluk Sultanate.[29]

In 1099, the Jews were among the rest of the population who tried in vain to defend Jerusalem against the Crusaders. When the city fell, a massacre of 6,000 Jews occurred when the synagogue they were seeking refuge in was set alight. Almost all perished.[30] The Jews almost single-handedly defended Haifa against the crusaders, holding out in the besieged town for a whole month (June–July 1099) in fierce battles. At this time, a full thousand years after the fall of the Jewish state, there were Jewish communities all over the country. Fifty of them are known and include Jerusalem, Tiberias, Ramleh, Ashkelon, Caesarea, and Gaza.[31][32]

In 1165 Maimonides visited Jerusalem and prayed on the Temple Mount, in the "great, holy house".[33] In 1141 Spanish poet, Yehuda Halevi, issued a call to the Jews to emigrate to the Land of Israel, a journey he undertook himself. In 1187 Ayyubid Sultan Saladin defeated the Crusaders in the Battle of Hattin and took Jerusalem and most of Palestine. In time, Saladin issued a proclamation inviting all Jews to return and settle in Jerusalem,[34] and according to Judah al-Harizi, they did: "From the day the Arabs took Jerusalem, the Israelites inhabited it."[35] al-Harizi compared Saladins decree allowing Jews to re-establish themselves in Jerusalem to the one issued by the Persian Cyrus the Great over 1,600 years earlier.[36]

In 1211, the Jewish community in the country was strengthened by the arrival of a group headed by over 300 rabbis from France and England,[37] among them Rabbi Samson ben Abraham of Sens.[38] Nachmanides, the 13th-century Spanish rabbi and recognised leader of Jewry greatly praised the land of Israel and viewed its settlement as a positive commandment incumbent on all Jews. He wrote "If the gentiles wish to make peace, we shall make peace and leave them on clear terms; but as for the land, we shall not leave it in their hands, nor in the hands of any nation, not in any generation."[39]

In 1260, control passed to the Egyptian Mamluks. In 1266 the Mamluk Sultan Baybars converted the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron into an exclusive Islamic sanctuary and banned Christians and Jews from entering, which previously would be able to enter it for a fee. The ban remained in place until Israel took control of the building in 1967.[40][41]

In 1470, Isaac b. Meir Latif arrived from Ancona and counted 150 Jewish families in Jerusalem.[42] Thanks to Joseph Saragossi who had arrived in the closing years of the 15th century, Safed and its environs had developed into the largest concentration of Jews in Palestine. With the help of the Sephardic immigration from Spain, the Jewish population had increased to 10,000 by the early 16th century.[43]

In 1516, the region was conquered by the Ottoman Empire; it remained under Turkish rule until the end of the First World War, when Britain defeated the Ottoman forces and set up a military administration across the former Ottoman Syria. In 1920 the territory was divided under the mandate system, and the area which included modern day Israel was named Mandatory Palestine.[29][44][45]

Zionism and the British mandate

[edit]

Since the Jewish diaspora, some Jews have aspired to return to "Zion" and the "Land of Israel",[46] though the amount of effort that should be spent towards such an aim was a matter of dispute.[47][48] The hopes and yearnings of Jews living in exile are an important theme of the Jewish belief system.[47] After the Jews were expelled from Spain in 1492, some communities settled in Palestine.[49] During the 16th century, Jewish communities struck roots in the Four Holy Cities—Jerusalem, Tiberias, Hebron, and Safed—and in 1697, Rabbi Yehuda Hachasid led a group of 1,500 Jews to Jerusalem.[50] In the second half of the 18th century, Eastern European opponents of Hasidism, known as the Perushim, settled in Palestine.[51][52][53]

"I believe that a wondrous generation of Jews will spring into existence. The Maccabeans will rise again. Let me repeat once more my opening words: The Jews who wish for a State will have it. We shall live at last as free men on our own soil, and die peacefully in our own homes. The world will be freed by our liberty, enriched by our wealth, magnified by our greatness. And whatever we attempt there to accomplish for our own welfare, will react powerfully and beneficially for the good of humanity."

The first wave of modern Jewish migration to Ottoman-ruled Palestine, known as the First Aliyah, began in 1881, as Jews fled pogroms in Eastern Europe.[55] Although the Zionist movement already existed in practice, Austro-Hungarian journalist Theodor Herzl is credited with founding political Zionism,[56] a movement which sought to establish a Jewish state in the Land of Israel, by elevating the Jewish Question to the international plane.[57] In 1896, Herzl published Der Judenstaat (The State of the Jews), offering his vision of a future Jewish state; the following year he presided over the first World Zionist Congress.[58]

The Second Aliyah (1904–14), began after the Kishinev pogrom; some 40,000 Jews settled in Palestine, although nearly half of them left eventually.[55] Both the first and second waves of migrants were mainly Orthodox Jews,[59] although the Second Aliyah included socialist groups who established the kibbutz movement.[60] During World War I, British Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour sent the Balfour Declaration of 1917 to Baron Rothschild (Walter Rothschild, 2nd Baron Rothschild), a leader of the British Jewish community, that stated that Britain intended for the creation of a Jewish homeland within the Palestinian Mandate.[61][62]

The Jewish Legion, a group primarily of Zionist volunteers, assisted, in 1918, in the British conquest of Palestine.[63] Arab opposition to British rule and Jewish immigration led to the 1920 Palestine riots and the formation of a Jewish militia known as the Haganah (meaning "The Defense" in Hebrew), from which the Irgun and Lehi, or Stern Gang, paramilitary groups later split off.[64] In 1922, the League of Nations granted Britain a mandate over Palestine under terms similar to the Balfour Declaration.[65] The population of the area at this time was predominantly Arab and Muslim, with Jews accounting for about 11%,[66] Christians 9.5%.[67]

The Third (1919–23) and Fourth Aliyahs (1924–29) brought an additional 100,000 Jews to Palestine.[55]

Finally, the rise of Nazism and the increasing persecution of Jews in the 1930s led to the Fifth Aliyah, with an influx of a quarter of a million Jews. This was a major cause of the Arab revolt of 1936–39 in which the British killed 5,032 Arabs and wounded 14,760,[68] and resulting in over ten percent of the adult male Palestinian Arab population killed, wounded, imprisoned or exiled.[69] The British introduced restrictions on Jewish immigration to Palestine with the White Paper of 1939. With countries around the world turning away Jewish refugees fleeing the Holocaust, a clandestine movement known as Aliyah Bet was organized to bring Jews to Palestine.[55] By the end of World War II, the Jewish population of Palestine had increased to 33% of the total population.[70]

Independence

[edit]The U.N partition resolution

[edit]

After World War II, Britain found itself in fierce conflict with the Jewish community over Jewish immigration limits, as well as continued conflict with the Arab community over limit levels. The Haganah joined Irgun and Lehi in an armed struggle against British rule.[71] At the same time, hundreds of thousands of Jewish Holocaust survivors and refugees sought a new life far from their destroyed communities in Europe. The Yishuv attempted to bring these refugees to Palestine but many were turned away or rounded up and placed in detention camps in Atlit and Cyprus by the British. Escalating violence culminated with the 1946 King David Hotel bombing which Bruce Hoffman characterized as one of the “most lethal terrorist incidents of the twentieth century."[72] In 1947, the British government announced it would withdraw from Mandatory Palestine, stating it was unable to arrive at a solution acceptable to both Arabs and Jews.

On 15 May 1947, the General Assembly of the newly formed United Nations resolved that a committee, United Nations Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP), be created "to prepare for consideration at the next regular session of the Assembly a report on the question of Palestine".[73] In the Report of the Committee dated 3 September 1947 to the UN General Assembly,[74] the majority of the Committee in Chapter VI proposed a plan to replace the British Mandate with "an independent Arab State, an independent Jewish State, and the City of Jerusalem ... the last to be under an International Trusteeship System".[75] On 29 November 1947, the General Assembly adopted a resolution recommending the adoption and implementation of the Plan of Partition with Economic Union as Resolution 181 (II).[76] The Plan attached to the resolution was essentially that proposed by the majority of the Committee in the Report of 3 September 1947.

The Jewish Agency, which was the recognized representative of the Jewish community, accepted the plan. The Arab League and Arab Higher Committee of Palestine rejected it, and indicated that they would reject any other plan of partition.[77][78]

The Independence war

[edit]

On the following day, the 1 December 1947, the Arab Higher Committee proclaimed a three-day strike, and Arab bands began attacking Jewish targets.[79] The Jews were initially on the defensive as civil war broke out, but gradually moved onto the offensive.[80] The Palestinian Arab economy collapsed and 250,000 Palestinian Arabs fled or were expelled.[81]

On 14 May 1948, the day before the expiration of the British Mandate, David Ben-Gurion, the head of the Jewish Agency, declared "the establishment of a Jewish state in Eretz-Israel, to be known as the State of Israel".[82][83] The only reference in the text of the Declaration to the borders of the new state is the use of the term, Eretz-Israel.[84]

The Kibbutzim, or collective farming communities, played a pivotal role in establishing the new state.[85]

The following day, the armies of four Arab countries—Egypt, Syria, Transjordan and Iraq—entered what had been British Mandatory Palestine, launching the 1948 Arab–Israeli War;[86][87] Contingents from Yemen, Morocco, Saudi Arabia and Sudan joined the war.[88][89] The apparent purpose of the invasion was to prevent the establishment of the Jewish state at inception, and some Arab leaders talked about driving the Jews into the sea. [90][91][92] According to Benny Morris, Jews felt that the invading Arab armies aimed to slaughter the Jews.[93] The Arab league stated that the invasion was to restore law and order and to prevent further bloodshed.[94]

After a year of fighting, a ceasefire was declared and temporary borders, known as the Green Line, were established.[95] Jordan annexed what became known as the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and Egypt took control of the Gaza Strip. The United Nations estimated that more than 700,000 Palestinians were expelled by or fled from advancing Israeli forces during the conflict—what would became known in Arabic as the Nakba ("catastrophe").[96]

The first years up to Suez Crisis

[edit]

Israel was admitted as a member of the United Nations by majority vote on 11 May 1949.[97] In the early years of the state, the Labor Zionist movement led by Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion dominated Israeli politics.[98][99]

Immigration to Israel during the late 1940s and early 1950s was aided by the Israeli Immigration Department and the non-government sponsored Organization for Illegal Immigration, called Mossad LeAliyah Bet. Both groups facilitated regular immigration logistics like arranging transportation, but the latter also engaged in clandestine operations in countries, particularly in the Middle East and Eastern Europe, where the lives of Jews were believed to be in danger and exit from those places was difficult. The Organization for Illegal Immigration continued to take part in immigration efforts until its disbanding in 1953.[100] An influx of Holocaust survivors and Jews from Arab and Muslim lands immigrated to Israel during the first 3 years and the number of Jews increased from 700,000 to 1,400,000.[101] Many of whom faced persecution and expulsion from their original countries.[102] The immigration was in accordance with the One Million Plan.

Consequently, the population of Israel rose from 800,000 to two million between 1948 and 1958.[101] Between 1948 and 1970, approximately 1,150,000 Jewish refugees relocated to Israel.[103] The immigrants came to Israel for differing reasons. Some believed in a Zionist ideology, while others moved to escape persecution. There were others that did it for the promise of a better life in Israel and a small number that were expelled from their homelands, such as British and French Jews in Egypt after the Suez Crisis.[104]

Some new immigrants arrived as refugees with no possessions and were housed in temporary camps known as ma'abarot; by 1952, over 200,000 immigrants were living in these tent cities.[105] During this period, food, clothes and furniture had to be rationed in what became known as the Austerity Period. The need to solve the crisis led Ben-Gurion to sign a reparations agreement with West Germany that triggered mass protests by Jews angered at the idea that Israel could accept monetary compensation for the Holocaust.[106]

In 1950 Egypt closed the Suez Canal to Israeli shipping and tensions mounted as armed clashes took place along Israel's borders.

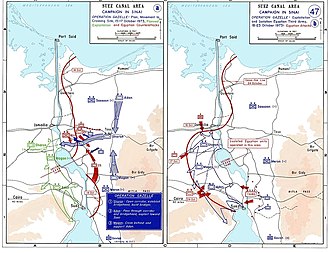

During the 1950s, Israel was frequently attacked by Palestinian fedayeen, mainly from the Egyptian-occupied Gaza Strip,[107] leading to several Israeli counter-raids. In 1956, Israel joined a secret alliance with Great Britain and France aimed at regaining control of the Suez Canal, which the Egyptians had nationalized (see the Suez Crisis). Israel overran the Sinai Peninsula but was pressured to withdraw by the United Nations in return for guarantees of Israeli shipping rights the Red Sea via the Straits of Tiran and the Canal[citation needed].[108][109] The war resulted in significant reduction of Israeli border infiltrations.[110][111][112][113]

The sixties

[edit]According to Tom Segev, the refugees were often treated differently according to where they were from. Jews of European descent were considered critical to the strengthening and peopling of Israel, so they were generally allowed to enter Israel first and thus were given abandoned Arab houses to live in. On the other hand, Jews from Middle Eastern and North African countries were viewed by many Ashkenazi Jews as lazy, poor, culturally and religiously backward, and a threat to established communal life in Israel and remained in transit camps for longer periods of time.[114] During the 1950s, the standard of living gap between Ashkenazi and Mizrahi Jews widened so much that tensions developed between the two groups. This tension first moved to hostility during the Wadi Salib riots in 1959; other instances of domestic turmoil would occur over the following decades.[115]

In the early 1960s, Israel captured Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann in Argentina and brought him to Israel for trial.[116] The trial had a major impact on public awareness of the Holocaust.[117] Eichmann remains the only person executed after conviction by an Israeli civilian court.[118]

The 1967 Six Day War and 1973 Yom Kippur War

[edit]

Since 1964, Arab countries, concerned over Israeli plans to divert waters of the Jordan River into the coastal plain,[119] had been trying to divert the headwaters to deprive Israel of water resources, provoking tensions between Israel on the one hand, and Syria and Lebanon on the other.

Arab nationalists led by Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser refused to recognize Israel, and called for its destruction.[120][121][122] By 1966, Israeli-Arab relations had deteriorated to the point of actual battles taking place between Israeli and Arab forces.[123] In May 1967, Egypt massed its army near the border with Israel, expelled UN peacekeepers, stationed in the Sinai Peninsula since 1957, and blocked Israel's access to the Red Sea. Other Arab states mobilized their forces as well.[124] Israel reiterated that these actions were a casus belli. On 5 June 1967, Israel launched a pre-emptive strike against Egypt. Jordan, Syria and Iraq responded and attacked Israel. In a Six-Day War, Israeli military superiority was clearly demonstrated against their more numerous Arab foes. Israel defeated Jordan and captured the West Bank, defeated Egypt and captured the Gaza Strip and Sinai Peninsula and defeated Syria and captured the Golan Heights.[125] Jerusalem's boundaries were enlarged, incorporating East Jerusalem, and the 1949 Green Line became the administrative boundary between Israel and the occupied territories.

Following the 1967 war, Israel faced much internal resistance from the Palestinians and Egyptian hostilities in the Sinai. Most important among the various Palestinian and Arab groups was the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO), established in 1964, which initially committed itself to "armed struggle as the only way to liberate the homeland".[126][127] In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Palestinian groups launched a wave of attacks[128][129] against Israeli and Jewish targets around the world,[130] including a massacre of Israeli athletes at the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich. The Israeli government responded with an assassination campaign against the organizers of the massacre, a bombing and a raid on the PLO headquarters in Lebanon.

On 6 October 1973, as Jews were observing Yom Kippur, the Egyptian and Syrian armies launched a surprise attack against Israeli forces in the Sinai Peninsula and Golan Heights, that opened the Yom Kippur War. The war ended on 26 October with Israel successfully repelling Egyptian and Syrian forces but having suffered over 2,500 soldiers killed in a war which collectively took between 10-35,000 lives in just 20 days.[131] An internal inquiry exonerated the government of responsibility for failures before and during the war, but public anger forced Prime Minister Golda Meir to resign.[132]

Further conflict and peace treaties

[edit]In July 1976 an airliner was hijacked during its flight to Tel Aviv by Palestinian guerrillas and landed at Entebbe, Uganda. Israeli commandos carried out Operation Entebbe in which 102 Israeli hostages were successfully rescued.

The 1977 Knesset elections marked a major turning point in Israeli political history as Menachem Begin's Likud party took control from the Labor Party.[133] Later that year, Egyptian President Anwar El Sadat made a trip to Israel and spoke before the Knesset in what was the first recognition of Israel by an Arab head of state.[134] In the two years that followed, Sadat and Begin signed the Camp David Accords (1978) and the Israel–Egypt Peace Treaty (1979).[135] In return, Israel withdrew from the Sinai Peninsula, which Israel had captured during the Six-Day War in 1967, and agreed to enter negotiations over an autonomy for Palestinians in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip.[136]

On 11 March 1978, a PLO guerilla raid from Lebanon led to the Coastal Road Massacre. Israel responded by launching an invasion of southern Lebanon to destroy the PLO bases south of the Litani River. Most PLO fighters withdrew, but Israel was able to secure southern Lebanon until a UN force and the Lebanese army could take over. The PLO soon resumed its policy of attacks against Israel. In the next few years, the PLO infiltrated the south and kept up a sporadic shelling across the border. Israel carried out numerous retaliatory attacks by air and on the ground.

Meanwhile, Begin's government provided incentives for Israelis to settle in the occupied West Bank, increasing friction with the Palestinians in that area.[137] The Basic Law: Jerusalem, the Capital of Israel, passed in 1980, was believed by some to reaffirm Israel's 1967 annexation of Jerusalem by government decree, and reignited international controversy over the status of the city. No Israeli legislation has defined the territory of Israel and no act specifically included East Jerusalem therein.[138] The position of the majority of UN member states is reflected in numerous resolutions declaring that actions taken by Israel to settle its citizens in the West Bank, and impose its laws and administration on East Jerusalem, are illegal and have no validity.[139] In 1981 Israel annexed the Golan Heights, although annexation was not recognized internationally.[140]

On 7 June 1981, the Israeli air force destroyed Iraq's sole nuclear reactor, in order to impede Iraq's nuclear weapons program. The reactor was under construction just outside Baghdad.

Following a series of PLO attacks in 1982, Israel invaded Lebanon that year to destroy the bases from which the PLO launched attacks and missiles into northern Israel.[141] In the first six days of fighting, the Israelis destroyed the military forces of the PLO in Lebanon and decisively defeated the Syrians. An Israeli government inquiry – the Kahan Commission – would later hold Begin, Sharon and several Israeli generals as indirectly responsible for the Sabra and Shatila massacre. In 1985, Israel responded to a Palestinian terrorist attack in Cyprus by bombing the PLO headquarters in Tunis. Israel withdrew from most of Lebanon in 1986, but maintained a borderland buffer zone in southern Lebanon until 2000.

Israel's ethnic diversity expanded in the 1980s and 1990s due to immigration. Several waves of Ethiopian Jews immigrated to Israel in the 1980s and 1990s and between 1990 and 1994, Russian immigration to Israel increased Israel's population by twelve percent.[142]

The First Intifada, a Palestinian uprising against Israeli rule,[143] broke out in 1987, with waves of uncoordinated demonstrations and violence occurring in the occupied West Bank and Gaza. Over the following six years, the Intifada became more organised and included economic and cultural measures aimed at disrupting the Israeli occupation. More than a thousand people were killed in the violence.[144] Responding to continuing PLO guerilla raids into northern Israel, Israel launched another punitive raid into southern Lebanon in 1988. Amid rising tensions over the Kuwait crisis, Israeli border guards fired into a rioting Palestinian crowd near the Al-Aqsa mosque in Jerusalem. 20 people were killed and some 150 injured. During the 1991 Gulf War, the PLO supported Saddam Hussein and Iraqi Scud missile attacks against Israel. Despite public outrage, Israel heeded US calls to refrain from hitting back and did not participate in that war.[145][146]

In 1992, Yitzhak Rabin became Prime Minister following an election in which his party called for compromise with Israel's neighbors.[147][148] The following year, Shimon Peres on behalf of Israel, and Mahmoud Abbas for the PLO, signed the Oslo Accords, which gave the Palestinian National Authority the right to govern parts of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip.[149] The PLO also recognized Israel's right to exist and pledged an end to terrorism.[150] In 1994, the Israel–Jordan Treaty of Peace was signed, making Jordan the second Arab country to normalize relations with Israel.[151] Arab public support for the Accords was damaged by the continuation of Israeli settlements[152] and checkpoints, and the deterioration of economic conditions.[153] Israeli public support for the Accords waned as Israel was struck by Palestinian suicide attacks.[154] Finally, while leaving a peace rally in November 1995, Yitzhak Rabin was assassinated by a far-right-wing Jew who opposed the Accords.[155]

At the end of the 1990s, Israel, under the leadership of Benjamin Netanyahu, withdrew from Hebron,[156] and signed the Wye River Memorandum, giving greater control to the Palestinian National Authority.[157] Ehud Barak, elected Prime Minister in 1999, began the new millennium by withdrawing forces from Southern Lebanon and conducting negotiations with Palestinian Authority Chairman Yasser Arafat and U.S. President Bill Clinton at the 2000 Camp David Summit. During the summit, Barak offered a plan for the establishment of a Palestinian state, but Yasser Arafat rejected it.[158] After the collapse of the talks and a controversial visit by Likud leader Ariel Sharon to the Temple Mount, the Second Intifada began, which was allegedly pre-planned by Yasser Arafat.[159][160][161] Sharon became prime minister in a 2001 special election. During his tenure, Sharon carried out his plan to unilaterally withdraw from the Gaza Strip and also spearheaded the construction of the Israeli West Bank barrier,[162] defeating the Intifada.[163][164][165][166][167][168][169][170][171][172][173][174]

In July 2006, a Hezbollah artillery assault on Israel's northern border communities and a cross-border abduction of two Israeli soldiers precipitated the month-long Second Lebanon War.[175][176] On 6 September 2007, the Israeli Air Force destroyed a nuclear reactor in Syria. In May 2008, Israel confirmed it had been discussing a peace treaty with Syria for a year, with Turkey as a go-between.[177] However, at the end of the year, Israel entered another conflict as a ceasefire between Hamas and Israel collapsed. The Gaza War lasted three weeks and ended after Israel announced a unilateral ceasefire.[178][179] Hamas announced its own ceasefire, with its own conditions of complete withdrawal and opening of border crossings. Despite neither the rocket launchings nor Israeli retaliatory strikes having completely stopped, the fragile ceasefire remained in order.[180] In what it said was a response to more than a hundred Palestinian rocket attacks on southern Israeli cities,[181] Israel began an operation in Gaza on 14 November 2012, lasting eight days.[182][183][184] Israel started another operation in Gaza following an escalation of rocket attacks by Hamas in July 2014.[185]

Geography

[edit]Climate

[edit]Demographic

[edit]Economy

[edit]Israel is considered one of the most advanced countries in Southwest Asia in economic and industrial development. Israel's quality university education and the establishment of a highly motivated and educated populace is largely responsible for spurring the country's high technology boom and rapid economic development. In 2010, it joined the OECD.[186] The country is ranked 3rd in the region and 38th worldwide on the World Bank's Ease of Doing Business Index as well as in the World Economic Forum's Global Competitiveness Report. It has the second-largest number of startup companies in the world (after the United States) and the largest number of NASDAQ-listed companies outside North America.

In 2010, Israel ranked 17th among the world's most economically developed nations, according to IMD's World Competitiveness Yearbook. The Israeli economy was ranked as the world's most durable economy in the face of crises, and was also ranked first in the rate of research and development center investments.

The Bank of Israel was ranked first among central banks for its efficient functioning, up from 8th place in 2009. Israel was also ranked as the worldwide leader in its supply of skilled manpower. The Bank of Israel holds $78 billion of foreign-exchange reserves.[187]

In July 2007, American business magnate and investor Warren Buffett's holding company Berkshire Hathaway bought an Israeli company, Iscar, its first non-U.S. acquisition, for $4 billion.[188] Since the 1970s, Israel has received military aid from the United States, as well as economic assistance in the form of loan guarantees, which now account for roughly half of Israel's external debt. Israel has one of the lowest external debts in the developed world, and is a net lender in terms of net external debt (the total value of assets vs. liabilities in debt instruments owed abroad), which in June 2012[update][[Category:Articles containing potentially dated statements from Expression error: Unexpected < operator.]] stood at a surplus of US$60 billion.[189]

Days of working time in Israel are Sunday through Thursday (for a five-day workweek), or Friday (for a six-day workweek). In observance of Shabbat, in places where Friday is a work day and the majority of population is Jewish, Friday is a "short day", usually lasting till 14:00 in the winter, or 16:00 in the summer. Several proposals have been raised to adjust the work week with the majority of the world, and make Sunday a non-working day, while extending working time of other days, and/or replacing Friday with Sunday as a work day.[190]

Science and technology

[edit]Israel has embraced solar energy; its engineers are on the cutting edge of solar energy technology and its solar companies work on projects around the world. Over 90% of Israeli homes use solar energy for hot water, the highest per capita in the world.[191] According to government figures, the country saves 8% of its electricity consumption per year because of its solar energy use in heating.[192] The high annual incident solar irradiance at its geographic latitude creates ideal conditions for what is an internationally renowned solar research and development industry in the Negev Desert.[193][194][195]

Israel is one of the world's technological leaders in water technology. In 2011, its water technology industry was worth around $2 billion a year with annual exports of products and services in the tens of millions of dollars. The ongoing shortage of water in the country has spurred in water conservation techniques, and a substantial agricultural modernization, drip irrigation, was invented in Israel. Israel is also at the technological forefront of desalination and water recycling. The Ashkelon seawater reverse osmosis (SWRO) plant, the largest in the world, was voted 'Desalination Plant of the Year' in the Global Water Awards in 2006. Israel hosts an annual Water Technology Exhibition and Conference (WaTec) that attracts thousands of people from across the world.[196][197] By the end of 2013, 85 percent of the country's water consumption will be from reverse osmosis. As a result of innovations in reverse osmosis technology, Israel is set to become a net exporter of water in the coming years.[198]

Israel had a modern electric car infrastructure involving a countrywide network of recharging stations to facilitate the charging and exchange of car batteries. It was thought that this would have lowered Israel's oil dependency and lowered the fuel costs of hundreds of Israel's motorists that use cars powered only by electric batteries.[199] The Israeli model was being studied by several countries and being implemented in Denmark and Australia.[200] However, Israel's trailblazing electric car company Better Place shut down in 2013.[201]

The

Transport

[edit]

Israel has 18,096 kilometers (11,244 mi) of paved roads,[202] and 2.4 million motor vehicles.[203] The number of motor vehicles per 1,000 persons was 324, relatively low with respect to developed countries.[203] Israel has 5,715 buses on scheduled routes,[204] operated by several carriers, the largest of which is Egged, serving most of the country. Railways stretch across 949 kilometers (590 mi) and are operated solely by government-owned Israel Railways[205] (All figures are for 2008). Following major investments beginning in the early to mid-1990s, the number of train passengers per year has grown from 2.5 million in 1990, to 35 million in 2008; railways are also used to transport 6.8 million tons of cargo, per year.[205]

Israel is served by two international airports, Ben Gurion International Airport, the country's main hub for international air travel near Tel Aviv-Yafo, Ovda Airport in the south, as well as several small domestic airports.[206] Ben Gurion, Israel's largest airport, handled over 12.1 million passengers in 2010.[207]

On the Mediterranean coast, Haifa Port is the country's oldest and largest port, while Ashdod Port is one of the few deep water ports in the world built on the open sea.[206] In addition to these, the smaller Port of Eilat is situated on the Red Sea, and is used mainly for trading with Far East countries.[206]

Tourism

[edit]Culture

[edit]Israel's diverse culture stems from the diversity of the population: Jews from diaspora communities around the world have brought their cultural and religious traditions back with them, creating a melting pot of Jewish customs and beliefs.[208] Israel is the only country in the world where life revolves around the Hebrew calendar. Work and school holidays are determined by the Jewish holidays, and the official day of rest is Saturday, the Jewish Sabbath.[209] Israel's substantial Arab minority has also left its imprint on Israeli culture in such spheres as architecture,[210] music,[211] and cuisine.[212]

Language

[edit]Religion

[edit]Israel and the Palestinian territories comprise the major part of the Holy Land, a region of significant importance to all Abrahamic religions – Jews, Christians, Muslims and Baha'is.

The religious affiliation of Israeli Jews varies widely: a social survey for those over the age of 20 indicates that 55% say they are "traditional", while 20% consider themselves "secular Jews", 17% define themselves as "Religious Zionists"; 8% define themselves as "Haredi Jews". While the ultra-Orthodox, or Haredim, represented only 5% of Israel's population in 1990, they are expected to represent more than one-fifth of Israel's Jewish population by 2028.

Making up 16% of the population, Muslims constitute Israel's largest religious minority. About 2% of the population is Christian and 1.5% is Druze. The Christian population primarily comprises Palestinian Christians, but also includes post-Soviet immigrants and the Foreign Laborers of multinational origins and followers of Messianic Judaism, considered by most Christians and Jews to be a form of Christianity. Members of many other religious groups, including Buddhists and Hindus, maintain a presence in Israel, albeit in small numbers. Out of more than one million immigrants from the former Soviet Union in Israel, about 300,000 are considered not Jewish by the Orthodox rabbinate.

The city of Jerusalem is of special importance to Jews, Muslims and Christians as it is the home of sites that are pivotal to their religious beliefs, such as the Israeli-controlled Old City that incorporates the Western Wall and the Temple Mount, the Al-Aqsa Mosque and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

The administrative center of the Bahá'í Faith and the Shrine of the Báb are located at the Bahá'í World Centre in Haifa and the leader of the faith is buried in Acre. Apart from maintenance staff, there is no Bahá'í community in Israel, although it is a destination for pilgrimages. Bahá'í o in Israel do not teach their faith to Israelis following strict policy. A few miles south of the Bahá'í World Centre is the Middle East centre of the reformist Ahmadiyya movement. It's mixed neighbourhood of Jews and Ahmadi Arabs is the only one of its kind in the country.

Literature

[edit]

Israeli literature is primarily poetry and prose written in Hebrew, as part of the renaissance of Hebrew as a spoken language since the mid-19th century, although a small body of literature is published in other languages, such as English. By law, two copies of all printed matter published in Israel must be deposited in the National Library of Israel at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. In 2001, the law was amended to include audio and video recordings, and other non-print media.[214] In 2011, 86 percent of the 6,302 books transferred to the library were in Hebrew.[215]

The Hebrew Book Week is held each June and features book fairs, public readings, and appearances by Israeli authors around the country. During the week, Israel's top literary award, the Sapir Prize, is presented.

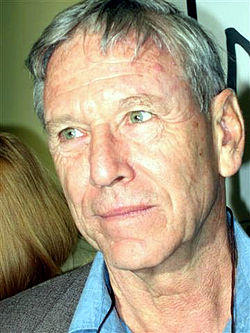

In 1966, Shmuel Yosef Agnon shared the Nobel Prize in Literature with German Jewish author Nelly Sachs.[216] Leading Israeli poets have been Yehuda Amichai, Nathan Alterman and Rachel Bluwstein. Internationally famous contemporary Israeli novelists include Amos Oz, Etgar Keret and David Grossman. The Israeli-Arab satirist Sayed Kashua (who writes in Hebrew) is also internationally known.

Israel has also been the home of two leading Palestinian poets and writers: Emile Habibi, whose novel The Secret Life of Saeed the Pessoptimist, and other writings, won him the Israel prize for Arabic literature; and Mahmoud Darwish, considered by many to be "the Palestinian national poet."[217] Darwish was born and raised in northern Israel, but lived his adult life abroad after joining the Palestine Liberation Organization.

Music and dance

[edit]Israeli music contains musical influences from all over the world; Sephardic music, Hasidic melodies, Belly dancing music, Greek music, jazz, and pop rock are all part of the music scene.[218][219]

The nation's canonical folk songs, known as "Songs of the Land of Israel," deal with the experiences of the pioneers in building the Jewish homeland.[221] The Hora circle dance introduced by early Jewish settlers was originally popular in the Kibbutzim and outlying communities. It became a symbol of the Zionist reconstruction and of the ability to experience joy amidst austerity. It now plays a significant role in modern Israeli folk dancing and is regularly performed at weddings and other celebrations, and in group dances throughout Israel.

Modern dance in Israel is a flourishing field, and several Israeli choreographers such as Ohad Naharin, Rami Beer, Barak Marshall and many others, are considered to be among the most versatile and original international creators working today. Famous Israeli companies include the Batsheva Dance Company and the Kibbutz Contemporary Dance Company.

Among Israel's world-renowned[222][223] orchestras is the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, which has been in operation for over seventy years and today performs more than two hundred concerts each year.[224] Israel has also produced many musicians of note, some achieving international stardom. Itzhak Perlman, Pinchas Zukerman and Ofra Haza are among the internationally acclaimed musicians born in Israel.

Israel has participated in the Eurovision Song Contest nearly every year since 1973, winning the competition three times and hosting it twice.[225][226] Eilat has hosted its own international music festival, the Red Sea Jazz Festival, every summer since 1987.[227]

Israel is home to many Palestinian musicians, including internationally acclaimed oud and violin virtuoso Taiseer Elias, singer Amal Murkus, and brothers Samir and Wissam Joubran. Israeli Arab musicians have achieved fame beyond Israel's borders: Elias and Murkus frequently play to audiences in Europe and America, and oud player Darwish Darwish (Prof. Elias's student) was awarded first prize in the all-Arab oud contest in Egypt in 2003. The Jerusalem Academy of Music and Dance has an advanced degree program, headed by Taiseer Elias, in Arabic music.

Cinema and theatre

[edit]

Ten Israeli films have been final nominees for Best Foreign Language Film at the Academy Awards since the establishment of Israel. The 2009 movie Ajami was the third consecutive nomination of an Israeli film.[228] Continuing the strong theatrical traditions of the Yiddish theatre in Eastern Europe, Israel maintains a vibrant theatre scene. Founded in 1918, Habima Theatre in Tel Aviv is Israel's oldest repertory theater company and national theater.[229] Palestinian Israeli filmmakers have made a number of films dealing with the Arab-Israel conflict and the status of Palestinians within Israel, such as Mohammed Bakri's 2002 film Jenin, Jenin and The Syrian Bride.

Media

[edit]In 2014, Israel proper was ranked 96th of 180 according to Reporters Without Borders' Press Freedom Index, 2nd below Kuwait (at 91) in the Middle East and North Africa region. The 2013 Freedom in the World annual survey and report by U.S.-based Freedom House, which attempts to measure the degree of democracy and political freedom in every nation, ranked Israel as the Middle E.ast and North Africa's only free country.

Museums

[edit]

The Israel Museum in Jerusalem is one of Israel's most important cultural institutions[230] and houses the Dead Sea scrolls,[231] along with an extensive collection of Judaica and European art.[230] Israel's national Holocaust museum, Yad Vashem, is the world central archive of Holocaust-related information.[232] Beth Hatefutsoth (the Diaspora Museum), on the campus of Tel Aviv University, is an interactive museum devoted to the history of Jewish communities around the world.[233]

Apart from the major museums in large cities, there are high-quality artspaces in many towns and kibbutzim. Mishkan Le'Omanut on Kibbutz Ein Harod Meuhad is the largest art museum in the north of the country.[234]

Several Israeli museums are devoted to Islamic culture, including the Rockefeller Museum and the L. A. Mayer Institute for Islamic Art, both in Jerusalem. The Rockefeller specializes in archaeological remains from the Ottoman and other periods of Middle East history. It is also the home of the first hominid fossil skull found in Western Asia called Galilee Man.[235] A cast of the skull is on display at the Israel Museum.[236]

Cuisine

[edit]

Israeli cuisine includes local dishes as well as dishes brought to the country by Jewish immigrants from the diaspora. Since the establishment of the State in 1948, and particularly since the late 1970s, an Israeli fusion cuisine has developed. Most Israeli food is kosher and cooked in accordance with the Jewish Halakha. Although most of its population is either Jewish or Muslim, pork is both produced and consumed in Israel.

Israeli cuisine has adopted, and continues to adapt, elements of various styles of Jewish cuisine, particularly the Mizrahi, Sephardic, and Ashkenazi styles of cooking, along with Moroccan Jewish, Iraqi Jewish, Ethiopian Jewish, Indian Jewish, Iranian Jewish and Yemeni Jewish influences. It incorporates many foods traditionally eaten in the Arab, Middle Eastern and Mediterranean cuisines, such as falafel, hummus, shakshouka, couscous, and za'atar, which have become common ingredients in Israeli cuisine. Schnitzel, pizza, hamburgers, French fries, rice and salad are also very common in Israel.

Sports

[edit]

The Maccabiah Games, an Olympic-style event for Jewish athletes and Israeli athletes, was inaugurated in the 1930s, and has been held every four years since then. In 1964 Israel hosted and won the Asian Nations Cup; in 1970 the Israel national football team managed to qualify to the FIFA World Cup, which is still considered the biggest achievement of Israeli football.

The 1974 Asian Games held in Tehran, were the last Asian Games in which Israel participated, and was plagued by the Arab countries which refused to compete with Israel, and Israel since ceased competing in Asian competitions.[237] Israel was excluded from the 1978 Asian Games due to security and expense involved if they were to participate.[238] In 1994, UEFA agreed to admit Israel and all Israeli sporting organizations now compete in Europe.

The most popular spectator sports in Israel are association football and basketball.[239] The Israeli Premier League is the country's premier football league, and the Israeli Basketball Super League is the premier basketball league.[240] Maccabi Haifa, Maccabi Tel Aviv, Hapoel Tel Aviv and Beitar Jerusalem are the largest sports clubs. Maccabi Tel Aviv, Maccabi Haifa and Hapoel Tel Aviv have competed in the UEFA Champions League and Hapoel Tel Aviv reached the UEFA Cup quarter-finals. Maccabi Tel Aviv B.C. has won the European championship in basketball six times.[241] Israeli tennis champion Shahar Pe'er ranked 11th in the world on 31 January 2011.

Chess is a leading sport in Israel and is enjoyed by people of all ages. There are many Israeli grandmasters and Israeli chess players have won a number of youth world championships.[242] Israel stages an annual international championship and hosted the World Team Chess Championship in 2005. The Ministry of Education and the World Chess Federation agreed upon a project of teaching chess within Israeli schools, and it has been introduced into the curriculum of some schools.[243][244][245] The city of Beersheba has become a national chess center, with the game being taught in the city's kindergartens. Owing partly to Soviet immigration, it is home to the largest number of chess grandmasters of any city in the world.[246][247] The Israeli chess team won the silver medal at the 2008 Chess Olympiad[248] and the bronze, coming in third among 148 teams, at the 2010 Olympiad. Israeli grandmaster Boris Gelfand won the Chess World Cup in 2009[249] and the 2011 Candidates Tournament for the right to challenge the world champion. He only lost the World Chess Championship 2012 to reigning world champion Anand after a speed-chess tie breaker.

Krav Maga, a martial art developed by Jewish ghetto defenders during the struggle against fascism in Europe, is used by the Israeli security forces and police. Its effectiveness and practical approach to self-defense, have won it widespread admiration and adherence round the world.

To date, Israel has won seven Olympic medals since its first win in 1992, including a gold medal in windsurfing at the 2004 Summer Olympics.[250] Israel has won over 100 gold medals in the Paralympic Games and is ranked about 15th in the all-time medal count. The 1968 Summer Paralympics were hosted by Israel.[251]

Education

[edit]

Israel has a school life expectancy of 15.5 years[252] and a literacy rate of 97.1% according to the United Nations.[253] The State Education Law, passed in 1953, established five types of schools: state secular, state religious, ultra orthodox, communal settlement schools, and Arab schools. The public secular is the largest school group, and is attended by the majority of Jewish and non-Arab pupils in Israel. Most Arabs send their children to schools where Arabic is the language of instruction.[254]

Education is compulsory in Israel for children between the ages of three and eighteen.[255][256] Schooling is divided into three tiers – primary school (grades 1–6), middle school (grades 7–9), and high school (grades 10–12) – culminating with Bagrut matriculation exams. Proficiency in core subjects such as mathematics, the Hebrew language, Hebrew and general literature, the English language, history, Biblical scripture and civics is necessary to receive a Bagrut certificate.[257] In Arab, Christian and Druze schools, the exam on Biblical studies is replaced by an exam on Muslim, Christian or Druze heritage.[258] Christian Arabs are one of the most educated groups in Israel.[259] Maariv have describe the Christian Arabs sectors as "the most successful in education system",[259] since Christian Arabs fared the best in terms of education in comparison to any other group receiving an education in Israel.[260]

In 2003, over half of all Israeli twelfth graders earned a matriculation certificate.[261] Israel also boasts a highly motivated and educated populace where in 2012, the country ranked third in the world in the number of academic degrees per capita (20 percent of the population).[262][263] In addition, the quality of Israeli university education is very high, robust, and prestigious. As many offerings are varied, Israeli universities are considered to be of top quality, and they are inexpensive to attend. The country has nine highly regarded research universities and 49 private colleges. Despite many incentives to study domestically, interest in studying abroad is very high among Israelis, with many expressing a desire to attending Ivy League institutions in United States. Other preferred destinations include Canada, Australia, the United Kingdom, and Eastern Europe.[264] Israel's quality university education is largely responsible for spurring the country's high technology boom and rapid economic development over the past 60 years.[264] The Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Tel Aviv University are ranked among the world's top 100 universities by Times Higher Education magazine.[265]

See also

[edit]- [[Archivo:

- REDIRECCIÓN Plantilla:Iconos|20px|Ver el portal sobre Israel]] Portal:Israel. Contenido relacionado con Israel.

- Index of Israel-related articles

- International rankings of Israel

- Outline of Israel

- State of Palestine

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "And the Lord thy God will bring thee into the land which thy fathers possessed, and thou shalt possess it; and he will do thee good, and multiply thee above thy fathers." (Deuteronomy 30:5).

- ^ "But if ye return unto me, and keep my commandments and do them, though your dispersed were in the uttermost part of the heaven, yet will I gather them from thence, and will bring them unto the place that I have chosen to cause my name to dwell there." (Nehemiah 1:9).

- ^ "Walking the Bible Timeline". Walking the Bible. Public Broadcast Television. Retrieved 29 September 2007.

- ^ Friedland & Hecht 2000, p. 8. "For a thousand years Jerusalem was the seat of Jewish sovereignty, the household site of kings, the location of its legislative councils and courts."

- ^ Ben-Sasson 1985

- ^ Matthews, Victor H. (2002). A Brief History of Ancient Israel. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-664-22436-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/Suggestions' not found.

- ^ Stager in Coogan 1998, p. 91.[Full citation needed]

- ^ Dever 2003, p. 206.Template:Title?

- ^ Miller 1986, pp. 78–9.Template:Title?

- ^ McNutt 1999, p. 35.Template:Title?

- ^ McNutt 1999, p. 70.Template:Title?

- ^ Miller 2005, p. 98.Template:Title?

- ^ McNutt 1999, p. 72.Template:Title?

- ^ Miller 2005, p. 99.Template:Title?

- ^ Miller 2005, p. 105.Template:Title?

- ^ Lehman in Vaughn 1992, pp. 156–62.[Full citation needed]

- ^ Gnuse 1997, pp.28,31Template:Title?

- ^ http://www.utexas.edu/courses/classicalarch/readings/sennprism.html column 2 line 61 to column 3 line 49

- ^ "British Museum - Cuneiform tablet with part of the Babylonian Chronicle (605-594 BC)". Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- ^ See http://www.livius.org/cg-cm/chronicles/abc5/jerusalem.html reverse side, line 12.

- ^ Judaism in late antiquity, Jacob Neusner, Bertold Spuler, Hady R Idris, BRILL, 2001, p. 155

- ^ Oppenheimer, A'haron and Oppenheimer, Nili. Between Rome and Babylon: Studies in Jewish Leadership and Society. Mohr Siebeck, 2005, p. 2.

- ^ Cohn-Sherbok, Dan (1996). Atlas of Jewish History. Routledge. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-415-08800-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Lehmann, Clayton Miles (18 January 2007). "Palestine". Encyclopedia of the Roman Provinces. University of South Dakota. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ^ Morçöl 2006, p. 304

- ^ The Abuhav Synagogue, Jewish Virtual Library.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Gil, Moshe (1997). A History of Palestine, 634–1099. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-59984-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Jump up to: a b Kramer, Gudrun (2008). A History of Palestine: From the Ottoman Conquest to the Founding of the State of Israel. Princeton University Press. p. 376. ISBN 978-0-691-11897-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Allan D. Cooper (2009). The geography of genocide. University Press of America. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-7618-4097-8. Retrieved 1 January 2012.

- ^ Katz, Shmuel. Battleground: Fact and Fantasy in Palestine. Taylor Productions Ltd., 1974 (ISBN 0-929093-13-5), pg. 97

- ^ Carmel, Alex. The History of Haifa Under Turkish Rule. Haifa: Pardes, 2002 (ISBN 965-7171-05-9), pp. 16-17

- ^ Sefer HaCharedim Mitzvat Tshuva Chapter 3. Maimonides established a yearly holiday for himself and his sons, 6 Cheshvan, commemorating the day he went up to pray on the Temple Mount, and another, 9 Cheshvan, commemorating the day he merited to pray at the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron.

- ^ Abraham P. Bloch (1987). "Sultan Saladin Opens Jerusalem to Jews". One a day: an anthology of Jewish historical anniversaries for every day of the year. KTAV Publishing House, Inc. p. 277. ISBN 978-0-88125-108-1. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- ^ Benzion Dinur (1974). "From Bar Kochba's Revolt to the Turkish Conquest". In David Ben-Gurion (ed.). The Jews in their Land. Aldus Books. p. 217. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- ^ Geoffrey Hindley (28 February 2007). Saladin: hero of Islam. Pen & Sword Military. p. xiii. ISBN 978-1-84415-499-9. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- ^ Alex Carmel; Peter Schäfer; Yossi Ben-Artzi (1990). The Jewish settlement in Palestine, 634-1881. L. Reichert. p. 31. ISBN 978-3-88226-479-1. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- ^ Samson ben Abraham of Sens, Jewish Encyclopedia.

- ^ Moshe Lichtman (September 2006). Eretz Yisrael in the Parshah: The Centrality of the Land of Israel in the Torah. Devora Publishing. p. 302. ISBN 978-1-932687-70-5. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- ^ M. Sharon (2010). "Al Khalil". Encyclopedia of Islam, Second Edition. Koninklijke Brill NV.

- ^ International Dictionary of Historic Places: Middle East and Africa by Trudy Ring, Robert M. Salkin, Sharon La Boda, pp. 336–339

- ^ Dan Bahat (1976). Twenty centuries of Jewish life in the Holy Land: the forgotten generations. Israel Economist. p. 48. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- ^ Fannie Fern Andrews (February 1976). The Holy Land under mandate. Hyperion Press. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-88355-304-6. Retrieved 25 December 2011.

- ^ "The Covenant of the League of Nations". Article 22. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ "Mandate for Palestine," Encyclopedia Judaica, Vol. 11, p. 862, Keter Publishing House, Jerusalem, 1972

- ^ Rosenzweig 1997, p. 1 "Zionism, the urge of the Jewish people to return to Palestine, is almost as ancient as the Jewish diaspora itself. Some Talmudic statements ... Almost a millennium later, the poet and philosopher Yehuda Halevi ... In the 19th century ..."

- ^ Jump up to: a b Geoffrey Wigoder, G.G. (ed.). "Return to Zion". The New Encyclopedia of Judaism (via Answers.Com). The Jerusalem Publishing House. Retrieved 8 March 2010.

{{cite journal}}:|author=has generic name (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ "An invention called 'the Jewish people'". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 18 April 2010. Retrieved 9 March 2010.

- ^ Gilbert 2005, p. 2. "Jews sought a new homeland here after their expulsions from Spain (1492) ..."

- ^ Eisen, Yosef (2004). Miraculous journey: a complete history of the Jewish people from creation to the present. Targum Press. p. 700. ISBN 1-56871-323-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Morgenstern, Arie (2006). Hastening redemption: Messianism and the resettlement of the land of Israel. USA: Oxford University Press. p. 304. ISBN 978-0-19-530578-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ "Jewish and Non-Jewish Population of Palestine-Israel (1517–2004)". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Barnai, Jacob (1992). The Jews in Palestine in the Eighteenth Century: Under the Patronage of the Istanbul committee of Officials for Palestine. University Alabama Press. p. 320. ISBN 978-0-8173-0572-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ The Jewish State, by Theodore Herzl, (Courier Corporation, 27 Apr 2012), page 157

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Immigration to Israel". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 29 March 2012. The source provides information on the First, Second, Third, Fourth and Fifth Aliyot in their respective articles. The White Paper leading to Aliyah Bet is discussed "Aliyah During World War II and its Aftermath".

- ^ Kornberg 1993 "How did Theodor Herzl, an assimilated German nationalist in the 1880s, suddenly in the 1890s become the founder of Zionism?"

- ^ Herzl 1946, p. 11

- ^ "Chapter One: The Heralders of Zionism". Jewish Agency for Israel. Retrieved 12 July 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Stein 2003, p. 88. "As with the First Aliyah, most Second Aliyah migrants were non-Zionist orthodox Jews ..."

- ^ Romano 2003, p. 30

- ^ Macintyre, Donald (26 May 2005). "The birth of modern Israel: A scrap of paper that changed history". The Independent. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- ^ Yapp, M.E. (1987). The Making of the Modern Near East 1792–1923. Harlow, England: Longman. p. 290. ISBN 0-582-49380-3.

- ^ Schechtman, Joseph B. (2007). "Jewish Legion". Encyclopaedia Judaica. Vol. 11. Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA. p. 304. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- ^ Scharfstein 1996, p. 269. "During the First and Second Aliyot, there were many Arab attacks against Jewish settlements ... In 1920, Hashomer was disbanded and Haganah ("The Defense") was established."

- ^ "League of Nations: The Mandate for Palestine, July 24, 1922". Modern History Sourcebook. Fordham University. 24 July 1922. Retrieved 27 August 2007.

- ^ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/Suggestions' not found.

- ^ "Report to the League of Nations on Palestine and Transjordan, 1937". British Government. 1937. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- ^ Hughes, M. (2009) The banality of brutality: British armed forces and the repression of the Arab Revolt in Palestine, 1936–39, English Historical Review Vol. CXXIV No. 507, 314–354.

- ^ Khalidi, Walid (1987). From Haven to Conquest: Readings in Zionism and the Palestine Problem Until 1948. Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 978-0-88728-155-6

- ^ "The Population of Palestine Prior to 1948". MidEastWeb. Retrieved 19 March 2012.

- ^ Fraser 2004, p. 27

- ^ Hoffman, Bruce (1999). Inside Terrorism. Columbia University Press. pp. 48–52.

- ^ "A/RES/106 (S-1)". General Assembly resolution. United Nations. 15 May 1947. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- ^ "A/364". Special Committee on Palestine. United Nations. 3 September 1947. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- ^ "Background Paper No. 47 (ST/DPI/SER.A/47)". United Nations. 20 April 1949. Retrieved 31 July 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "A/RES/181(II) of 29 November 1947". United Nations. 1947. Retrieved 30 May 2012.

- ^ Benny Morris (2008). 1948: a history of the first Arab-Israeli war. Yale University Press. pp. 66, 67, 72. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

p.66, at 1946 "The League demanded independence for Palestine as a "unitary" state, with an Arab majority and minority rights for the Jews." ; p.67, at 1947 "The League's Political Committee met in Sofar, Lebanon, on 16–19 September, and urged the Palestine Arabs to fight partition, which it called "aggression," "without mercy." The League promised them, in line with Bludan, assistance "in manpower, money and equipment" should the United Nations endorse partition." ; p. 72, at Dec 1947 "The League vowed, in very general language, "to try to stymie the partition plan and prevent the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine

- ^ Bregman 2002, pp. 40–41

- ^ Gelber, Yoav (2006). Palestine 1948. Brighton: Sussex Academic Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-902210-67-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Tal, David (2003). War in Palestine, 1948: Israeli and Arab Strategy and Diplomacy. Routledge. p. 471. ISBN 978-0-7146-5275-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Morris, Benny (2008). 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-15112-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ "Declaration of Establishment of State of Israel". Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 14 May 1948.

- ^ Clifford, Clark, "Counsel to the President: A Memoir", 1991, p. 20.

- ^ Jacobs, Frank (7 August 2012). "The Elephant in the Map Room". Borderlines. The New York Times. Retrieved 3 September 2012.

- ^ "The Kibbutz & Moshav: History & Overview". Jewish Virtual Library. Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ^ Karsh, Efraim (2002). The Arab–Israeli conflict: The Palestine War 1948. Osprey Publishing. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-84176-372-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Ben-Sasson 1985, p. 1058

- ^ Morris, 2008, p. 205Template:Title?

- ^ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/Suggestions' not found.

- ^ David Tal (24 June 2004). War in Palestine, 1948: Israeli and Arab Strategy and Diplomacy. Routledge. p. 469. ISBN 978-1-135-77513-1.

some of the Arab armies invaded Palestine in order to prevent the establishment of a Jewish state, Transjordan...

- ^ Benny Morris (1 April 2009). 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War. Yale University Press. p. 396. ISBN 978-0-300-15112-1.

The Arab war aim, in both stages of the hostilities, was, at a minimum, to abort the emergence of a Jewish state or to destroy it at inception. The Arab states hoped to accomplish this by conquering all or large parts of the territory allotted to the Jews by the United Nations. And some Arab leaders spoke of driving the Jews into the sea19 and ridding Palestine "of the Zionist plague."20 The struggle, as the Arabs saw it, was about the fate of Palestine/ the Land of Israel, all of it, not over this or that part of the country. But, in public, official Arab spokesmen often said that the aim of the May 1948 invasion was to "save" Palestine or "save the Palestinians," definitions more agreeable to Western ears.

- ^ Benny Morris (1 April 2009). 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War. Yale University Press. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-300-15112-1.

A week before the armies marched, Azzam told Kirkbride: "It does not matter how many [ Jews] there are. We will sweep them into the sea." ... Ahmed Shukeiry, one of Haj Amin al-Husseini's aides (and, later, the founding chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization), simply described the aim as "the elimination of the Jewish state." ...al-Quwwatli told his people: "Our army has entered ... we shall win and we shall eradicate Zionism)

- ^ Benny Morris (1 April 2009). 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War. Yale University Press. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-300-15112-1.

the Jews felt that the Arabs aimed to reenact the Holocaust and that they faced certain personal and collective slaughter should they lose

- ^ "PDF copy of Cablegram from the Secretary-General of the League of Arab States to the Secretary-General of the United Nations: S/745: 15 May 1948". Un.org. 9 September 2002. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- ^ Karsh, Efraim (2002). The Arab–Israeli conflict: The Palestine War 1948. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-372-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Morris, Benny. The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. p. 602. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ "Two Hundred and Seventh Plenary Meeting". The United Nations. 11 May 1949. Retrieved 13 July 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Lustick 1988, pp. 37–39

- ^ "Israel (Labor Zionism)". Country Studies. Library of Congress. Retrieved 12 February 2010.

- ^ Segev, Tom. 1949: The First Israelis. "The First Million". Trans. Arlen N. Weinstein. New York: The Free Press, 1986. Print. p 105-107

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Population, by Religion and Population Group" (PDF). Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. 2006. Retrieved 7 August 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Shulewitz, Malka Hillel (2001). The Forgotten Millions: The Modern Jewish Exodus from Arab Lands. Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8264-4764-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Bard, Mitchell (2003). The Founding of the State of Israel. Greenhaven Press. p. 15.

- ^ Laskier, Michael "Egyptian Jewry under the Nasser Regime, 1956–70" pages 573–619 from Middle Eastern Studies, Volume 31, Issue # 3, July 1995 page 579.

- ^ Hakohen, Devorah (2003). Immigrants in Turmoil: Mass Immigration to Israel and Its Repercussions in the 1950s and After. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-2969-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); for ma'abarot population, see p. 269. - ^ Shindler 2002, pp. 49–50

- ^ Gilbert 2005, p. 58

- ^ Schoenherr, Steven (15 December 2005). "The Suez Crisis". Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- ^ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/Suggestions' not found.

- ^ Benny Morris (25 May 2011). Righteous Victims: A History of the Zionist-Arab Conflict, 1881-1998. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. pp. 300, 301. ISBN 978-0-307-78805-4.

(p. 300) In exchange (for Israeli withdrawal) the United states had indirectly promised to guarantee Israel's right of passage through the straits (to the Red sea) and its right to self defense if the Egyptian closed them....(p 301) The 1956 war resulted in a significant reduction of...Israeli border tension. Egypt refrained from reactivating the Fedaeen, and...Egypt and Jordan made great effort to curb infiltration

- ^ "National insurance institute of Israel, Hostile Action Casualties" (in Hebrew).

list of people who were kiled in hostile action: 53 In 1956,19 in 1957, 15 in 1958

{{cite web}}: External link in|quote= - ^ "jewish virtual library, Terrorism Against Israel: Number of Fatalities".

53 at 1956, 19 at 1957, 15 at 1958

- ^ "Jewish virtual library,MYTH "Israel's military strike in 1956 was unprovoked."".

Israeli Ambassador to the UN Abba Eban explained ... As a result of these actions of Egyptian hostility within Israel, 364 Israelis were wounded and 101 killed. In 1956 alone, as a result of this aspect of Egyptian aggression, 28 Israelis were killed and 127 wounded.

- ^ Segev 2007, pp. 155–157

- ^ Massad, Joseph. "Zionism's Internal Others: Israel and the Oriental Jews." Journal of Palestine Studies 25.4 (1996): 53-68. PDF. p 59-64

- ^ "Adolf Eichmann". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 18 September 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Cole 2003, p. 27. "... the Eichmann trial, which did so much to raise public awareness of the Holocaust ..."

- ^ Shlomo Shpiro (2006). "No place to hide: Intelligence and civil liberties in Israel". Cambridge Review of International Affairs. 19 (44): 629–648.

- ^ "The Politics of Miscalculation in the Middle East", by Richard B. Parker (1993 Indiana University Press) pp. 38

- ^ Template:Harvnb

- ^ Maoz, Moshe (1995). Syria and Israel: From War to Peacemaking. USA: Oxford University Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-19-828018-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ "On This Day 5 Jun". BBC. 5 June 1967. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- ^ Segev 2007, p. 178

- ^ Segev 2007, p. 289

- ^ Smith 2006, p. 126. "Nasser, the Egyptian president, decided to mass troops in the Sinai ... casus belli by Israel."

- ^ Bennet, James (13 March 2005). "The Interregnum". The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved 11 February 2010.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ "Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs – The Palestinian National Covenant- July 1968". Mfa.gov.il. Retrieved 13 March 2009.

- ^ Silke, Andrew (2004). Research on Terrorism: Trends, Achievements and Failures. Routledge. p. 149 (256 pages). ISBN 978-0-7146-8273-0. Retrieved 8 March 2010.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Gilbert, Martin (2002). The Routledge Atlas of the Arab–Israeli Conflict: The Complete History of the Struggle and the Efforts to Resolve It. Routledge. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-415-28116-4. Retrieved 8 March 2010.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Andrews, Edmund; Kifner, John (27 January 2008). "George Habash, Palestinian Terrorism Tactician, Dies at 82". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ "1973: Arab states attack Israeli forces". On This Day. The BBC. 6 October 1973. Retrieved 15 July 2007.

- ^ "Agranat Commission". Knesset. 2008. Retrieved 8 April 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Bregman 2002, pp. 169–170 "In hindsight we can say that 1977 was a turning point ..."

- ^ Bregman 2002, pp. 171–174

- ^ Bregman 2002, pp. 186–187

- ^ Bregman 2002, pp. 186

- ^ Cleveland, William L. (1999). A history of the modern Middle East. Westview Press. p. 356. ISBN 978-0-8133-3489-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Lustick, Ian (1997). "Has Israel Annexed East Jerusalem?" (PDF). Middle East Policy. V (1). Washington, D.C.: Wiley-Blackwell: 34–45. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4967.1997.tb00247.x. ISSN 1061-1924. OCLC 4651987544. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ See for example UN General Assembly resolution 63/30, passed 163 for, 6 against "Resolution adopted by the General Assembly". 23 January 2009.

- ^ BBC News. Regions and territories: The Golan Heights.

- ^ Bregman 2002, p. 199

- ^ Friedberg, Rachel M. (November 2001). "The Impact of Mass Migration on the Israeli Labor Market" (PDF). The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 116 (4): 1373. doi:10.1162/003355301753265606.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Tessler, Mark A. (1994). A History of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. Indiana University Press. p. 677. ISBN 978-0-253-20873-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Stone & Zenner 1994, p. 246. "Toward the end of 1991 ... were the result of internal Palestinian terror."

- ^ Haberman, Clyde (9 December 1991). "After 4 Years, Intifada Still Smolders". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 March 2008.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Mowlana, Gerbner & Schiller 1992, p. 111

- ^ Bregman 2002, p. 236

- ^ "From the End of the Cold War to 2001". Boston College. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- ^ "The Oslo Accords, 1993". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 30 March 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Israel-PLO Recognition – Exchange of Letters between PM Rabin and Chairman Arafat – Sept 9- 1993". Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 31 March 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Harkavy & Neuman 2001, p. 270. "Even though Jordan in 1994 became the second country, after Egypt to sign a peace treaty with Israel ..."

- ^ "Sources of Population Growth: Total Israeli Population and Settler Population, 1991–2003". Settlements information. Foundation for Middle East Peace. Retrieved 20 March 2012.